It’s not particularly shocking to declare that superhero movies are bigger now than they’ve ever been at any point. By any anecdotal, statistical, or critical metric, superhero movies are everywhere and growing fast. This year’s highest-grossing film so far, Guardians of the Galaxy, pulled off the rare American box office feat of leaving the #1 weekend spot after its release, only to later circle around and reclaim it. Captain America: The Winter Soldier was the year’s top offering until Guardians surpassed it. And starting next year, we’re going to be hit by an even bigger wave of superhero movies. And the year after that. And the one after that. And so on.

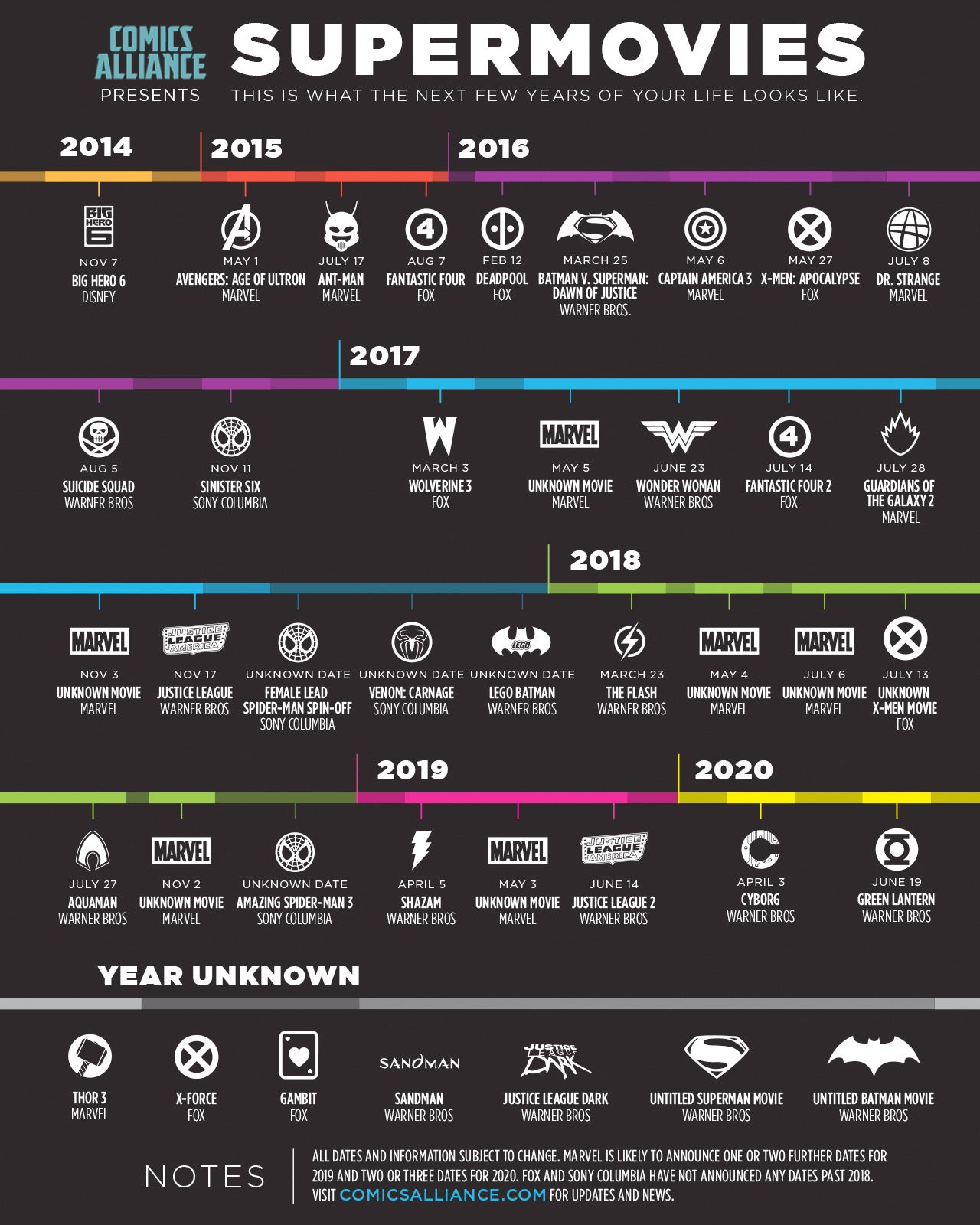

Over the past few days, Comics Alliance’s infographic about the current slate of planned/semi-announced superhero movies between now and 2020 has made the viral rounds, in large part because of the overwhelming scale of it all.

That’s an overwhelming amount of movies. That’s 40 hypothetical superhero movies to be released, starting with next month’s Big Hero 6, all within a six-year timeframe. That’s not even including the possibility of additional Marvel dates, as the infographic acknowledges at the bottom. So, we’re looking at a slate of roughly 7-8 superhero movies or more a year for the next six years. Nearly every month for the next six years will have at least one superhero entry courtesy of Fox (X-Men, Fantastic Four), Sony (Spider-Man), Warner Bros. (Batman, Superman, and the rest of the DC Universe) and Disney/Marvel Studios (pretty much everything and everyone else).

Warner is a particularly interesting case, as they’re woefully late to the party. Where Marvel started planting seeds for their monolith in May 2008 with Iron Man, Warner’s realization that they own enough properties to attempt to compete with Disney came after The Avengers already solidified Marvel as a box-office force of nature, and now, increasingly, the announcement of ten DC films between now and 2020 smacks of a mixture of desperation and avarice.

The Washington Post’s Stephanie Merry illustrated this point well in a recent piece predicting the much-discussed crash of the system. “Decades from now, cinephiles will look back on the early 2000s as the Superhero Era—and they’ll be able to pinpoint the moment when the bubble burst,” Merry wrote. “As with all trends, it’s only a matter of time. It happened with film noir and then westerns, it happened to the spy movies of the 1960s, and then to the gritty crime dramas of the ’70s.”

She continued, “And that’s why Warner Bros.’ plan [for DC movies] seems so short-sighted. The company is so focused on dethroning Marvel as the reigning box office champ that it’s missing the big picture: Superheroes may be invincible on screen, but their popularity won’t last forever. And the upcoming glut of movies might just speed their demise.”

All trends in popular culture are ephemeral, and it’s a point that, as Merry noted, is often forgotten in studios’ haste to turn a profit on a property that’s proven lucrative beyond almost any traditional definition. At the very least, it’s given fans a lot to talk about. Seemingly every day there’s a new announcement about a Spider-Man reboot or another DC character getting the solo feature treatment or Marvel digging into the same far-flung corners of their canon that yielded the lovable Guardians in search of the next game-changing hit. And the denizens of the internet have responded in kind, poring over trade rumors like a battalion of Variety-hoarding studio heads trying to be the first ones to the party.

It’s strange seeing such behavior, because it’s not how film geeks have historically functioned on the Internet. If the stereotype is that online film culture is a place where devotees go to obsess over minutiae and argue about whether Han did indeed shoot first (he didn’t until Lucas got involved, but I digress), it’s now become a hotbed for speculation over movies that haven’t moved far along enough in the development process to actually exist. Where once the territory of online speculation was shot-for-shot debates about Fight Club, now it’s about who exactly will play Doctor Strange, or which source materials will be used for the next Avengers.

Even the ways in which the actual movies are talked about are reflective of this. Ever since Marvel perfected the use of a post-credits stinger to hype the next installment in store (the jokey entries for Guardians and Avengers notwithstanding), it frequently seems as though there’s more talk after each release about what that could mean for the next release than there is about the movie itself.

While Merry is absolutely correct in acknowledging that superhero movies are following the same trajectory as other massive genre movie booms of past generations, what’s unique about the superhero boom is that it’s coming at a time (and largely because of) the globalized film economy, where American movies are now integrated brands being sold to far more people than just Americans. Over at Grantland, Mark Harris chronicled the possible hazards of trying to churn out the maximum number of films possible to reach for the biggest audience imaginable:

There is a wishful whiff of ‘too big to fail’ thinking, if not outright tulip fever, about this multi-studio scrum involving dozens of projects, billions of dollars, and the fervent belief that the audience will remain big enough to prevent these movies from cannibalizing one another.

There’s a lot more talk floating around in online spheres about the inevitable failure of everything promised in that infographic than there is about the movies, about whether they’ll be any good, what have you. Instead of talking about whether or not there’s enough interesting material to sustain any of these movies, even if the films eventually break from established canon (already happening, and will have to even more if this schedule holds true), we talk about hypothetical performance figures and what each movie will need to do to outpace its predecessor and thus spawn the all-important next chapter. The opacity of market structures in the online era has made it so that part of superhero film geekdom now apparently includes a rudimentary understanding of globalized marketing.

It seems almost antithetical to the spirit of the superhero movie, does it not? As soon as the thirst for one film is quenched, it’s immediately on to the next. It makes sense in a digital world where speed and being the first finger to hit the button have become the most profitable currencies, but at what price? Rather than being immersed in the worlds and lives of larger-than-life figures, we clamor for two hours with them at a time. Yet, we reduce those hours to one facet of a broader long-term portfolio, those two hours rendered tertiary in the face of figuring out when the next one is coming.

And with 40 or so more films on the way, at least until the inevitable popping of the bubble happens, it’s only going to continue on a path of us going to the movies as a necessary function of being able to talk ad nauseum about the movies.

Photo via JD Hancock/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)