If you subscribe to a subscription music service such as Spotify or Apple Music you probably pay $10 a month. And if you are like most people, you probably do so believing your money goes to the artists you listen to. Unfortunately, you are wrong.

The reality is only some of your money is paid to the artists you listen to. The rest of your money (and it’s probably most of your money) goes somewhere else. That “somewhere else” is decided by a small group of subscribers who have gained control over your money thanks to a mathematical flaw in how artist royalties are calculated. This flaw cheats real artists with real fans, rewards fake artists with no fans, and perhaps worst of all communicates to most streaming music subscribers a simple, awful, message: Your choices don’t count, and you don’t matter.

If you love music and want your money to go to the artists that you listen to, consider this simple hack. It’s easy to do, breaks no laws, does not violate any terms of service, directs more money to your favorite artists, but doesn’t actually require you to listen to any music, and best of all, it could force the music industry to make streaming royalties fair(er) for everyone. Sounds good, right?

So let’s cut to the chase. Here’s the hack: This September, when you aren’t listening to music, put your favorite indie artists on repeat, and turn the sound down.

You might be saying, “Wait a second, turn the sound down? How the heck does that do anything?”

Good question, let me explain.

The flaw in the big pool

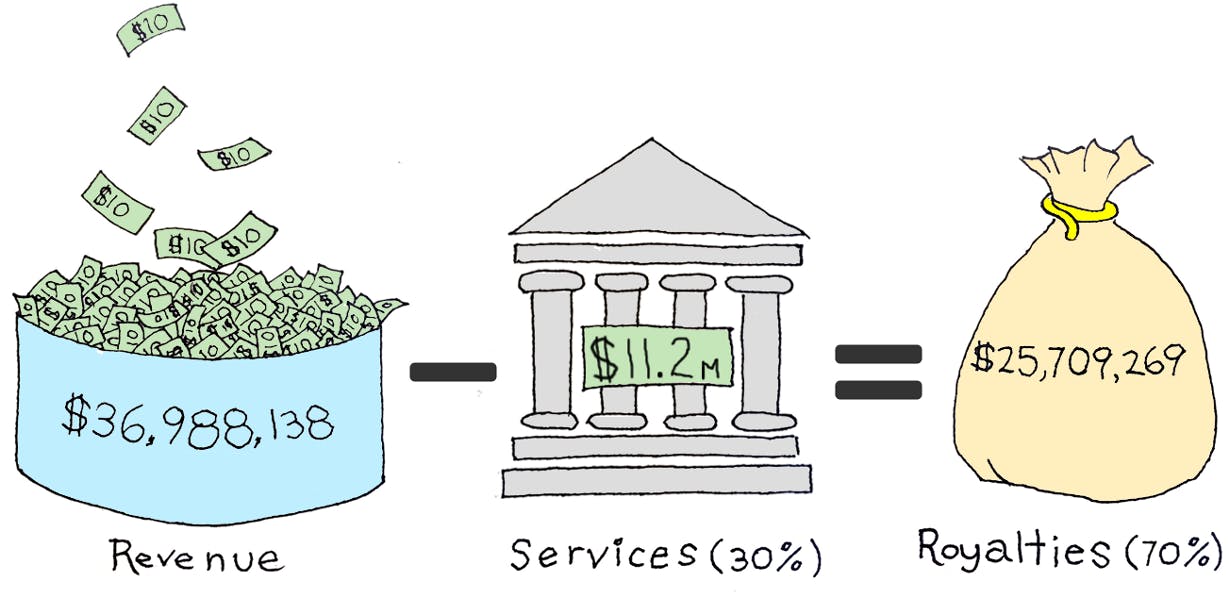

Streaming services (Spotify, Apple, etc.) calculate royalties for artists by putting all of the subscription revenue in one big pool. The services then take out 30 percent for themselves. The remaining 70 percent is set aside for royalties.

This giant bag of royalties is then divided by the overall number of streams (aka “plays” or “listens”). The result is called the “per-stream royalty rate.”

The problem lies in the fact that this “Big Pool method” only cares about one thing, and one thing only: the overall number of streams. It does not care even a tiny little bit about how many subscribers generated those streams.

So why is this bad?

You are worthless

Imagine a hypothetical artist on a streaming service. Which do you think that artist would rather have: 10,000 fans who stream a song once, or one fan who streams it 10,001 times? Seems obvious, right? Ten thousand fans is much better than one fan! But the Big Pool method, which only cares about the number of clicks, says the single person is worth more!

The message to artists and fans is crystal clear: the only fans that matter are the ones who click a lot. Everyone else can suck it.

Ass backward

This is bad for the artist, but astoundingly it’s even worse for streaming services: iI each subscriber is paying $10 a month then those 10,000 subscribers would generate $1.2M in annual revenue, while the single user only generates a measly $120. Clearly the services benefit from getting more subscribers, not more streams, so why are they incentivizing streams and ignoring subscribers?

Even more backwards, the Big Pool method encourages the acquisition of heavy-usage subscribers, who are the easiest customers to get and retain (in fact most “music afficianados” are already subscribers) but offers little for light-usage subscribers, who are not only the hardest customers to get and retain, but are more profitable (by not requiring as much bandwidth) and most importantly dramatically greater in number.

It’s as if a car dealership paid the biggest commissions to the employees who sold the fewest number of cheap cars, and completely stiffed the employees who sold lots of expensive ones.

But wait, it gets worse

If the Big Pool rewards artists who get lots of streams, major labels can sign artists who can get a lot of streams. But what if artists aren’t the only ones getting lots of streams?

Click fraud is rarely discussed in the context of streaming music, but it’s fairly simple for a fraudster to generate more in royalties than they pay in subscription fees. All a fraudster has to do is set up a fake artist account with fake music, and then they can use bots to generate clicks for their pretend artist. If each stream is worth $0.007 a click, the fraudster only needs 1,429 streams to make their $10 subscription fee back, at which point additional clicks are pure profit.

The message to artists and fans is crystal clear: the only fans that matter are the ones who click a lot.

But that’s assuming they even paid $10 for the subscription in the first place: It’s possible to purchase stolen premium accounts on the black market, making the scheme profitable almost immediately. The potential profits are substantial: At Spotify, it only takes 31 seconds of streaming to trigger a royalty payment, which means as many as 86,400 streams a month can be generated, resulting in over $600 of royalties. At Apple Music the threshold is just 20 seconds, making it hypothetically possible to clear 129,600 streams and $900 in royalties in just one month.

Awareness of click fraud in streaming music is so widespread that developers make apps to facilitate it. The services will tell you they work hard to make their systems secure, they pay bounties for people to find bugs, and once in a while they even catch and ban click frauders. But security researchers are not impressed, many people are not getting caught, and ultimately we have to confront the simple fact that there is no such thing as a foolproof way to prevent click fraud.

If the amount of click fraud activity on Google, Facebook, and Twitter is any indication (estimated to be over $6 billion a year), the problem could be far worse than any of the services will admit—or possibly even realize—and there’s no way for artists or fans to determine how much revenue has been stolen. It’s like someone sucking the oil out from under your property: You don’t even know it’s happening.

Click fraud is not the only way to cheat the system. One band made an album of completely silent tracks and told their “fans” to play the blank album on repeat while they slept. If a subscriber did as instructed, the band earned $195 in royalties from that single subscriber in just one month. But if each subscriber only pays $10 in subscription fees, then where did the other $185 come from?

It came from people like you.

The media suggests that Spotify was the one being “scammed” by this “clever” and “brilliant” stunt, but in reality, Spotify suffered no financial loss at all. The $20,000 that the band received didn’t come out of Spotify’s pockets, it came out of the 70 percent in royalties earmarked for artists. In essence, what happened is every artist on Spotify got paid a little less thanks to an album with no music on it.

To understand why, we need to talk about how “average” can be an illusion.

Average does not mean typical

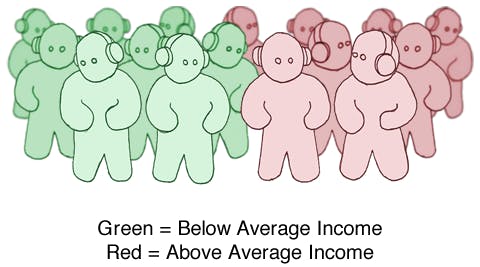

One of the most misleading words used in the streaming music industry is the word “average.” You’ll often see streaming services bragging about how their “average” user is streaming x number of hours per day, particularly when they are pitching advertisers. But don’t be fooled by the word “average” here—it’s an illusion. Average does not mean typical.

Think of it this way: Imagine you are in a room with a random group of people. What is the average income of everyone in the room? It’s likely that roughly half will be above average, and the other half will be below average.

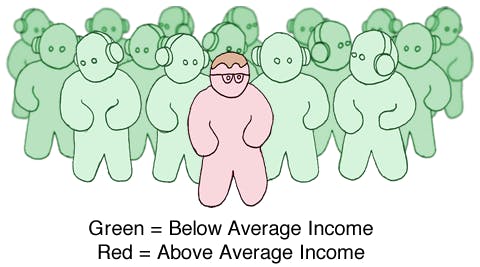

Now what happens when Bill Gates walks into the room?

Everyone in the room is below average now, thanks to Bill.

The same effect is happening in streaming music: A small number of super-heavy-usage subscribers have raised the “average” usage to the point that most subscribers are now below average.

We can illustrate this with a graph:

To understand how heavy-users wind up in control of your money, it helps to look at how royalties flow at the individual level:

Every user pays $10 a month, which generates $7 in royalties. If the per-stream rate of $0.007 is determined by dividing overall revenue by overall plays, then simple math tells us the “average” subscriber is streaming 1,000 times (1,000 x $0.007 = $7.00).

So if you stream 200 tracks in a month you will send $1.40 to the artists you listened to (200 x $0.007 = $1.40), and the remaining $5.60 of your $7 is now up for grabs. So who’s grabbing it?

But if each subscriber only pays $10 in subscription fees, then where did the other $185 come from? It came from people like you.

Well, let’s imagine a heavy-user who streams 1,800 tracks in a month. As a result of all this streaming, they send $12.60 in royalties to the artists they listen to (1,800 $0.007 = $12.60). Since they only contributed $7 towards royalties, they are $5.60 short. Guess where that money comes from?

You.

It’s worth noting that many (if not most) of these heavy-usage “subscribers” are probably not individuals at all. They are actually offices, restaurants, gyms, hair salons, etc. Businesses like these can stream up to 24 hours a day—far more you as an individual could ever hope to do. And they probably don’t share your taste in music either. But they pay the same $10 you do, so why do they get to decide where your money goes?

It’s like you bought a CD and the store told you that you had to listen to it 1,000 times, or they will give your money to Nickelback.

That’s fucked up.

The subscriber share method

There is a better way to approach streaming royalties, one which addresses all of these problems, and it’s called Subscriber Share.

The premise behind Subscriber Share is simple: The only artists that should receive your money are the artists you listen to. Subscriber Share simply divides up your $7 based on how much time you spend listening to each artist. So if you listen to an artist exclusively, then that artist will get the entire $7, but if you listen less, they get proportionately less.

As an example, if you listen to Alt-J 25 percent of the time, then Alt-J would get $1.75 ($7.00 x 25% = $1.75):

Let’s compare this with the Big Pool: If you typically stream 200 streams per month (that’s roughly 13 hours of streaming), then playing Alt-J 25 percent of the time would equal 50 streams. Since each stream gets a flat $0.007 per stream, the band will receive just 35 cents. (50 x $0.007 = $0.35)

Click here to see how this looks in real life, with a real subscriber.

But what about click fraud?

A nice feature of Subscriber Share is that it is very difficult to turn a profit with click fraud: Instead of turning $10 into $600, a fraudster would be turning $10 into $7 and would waste a lot of bandwidth while doing so.

If the fraudster used stolen premium accounts (reducing their cost from $10 to $1 per account), they could still make as much as $6 per account, but that is nowhere near as attractive as making $600, is it? And the difficulty level to do this at scale goes way up. If the industry switched to Subscriber Share, most click frauders would move to greener pastures.

Mission Impossible: Minimum Wage

Subscriber Share can also be a huge benefit to small bands just starting out. If a band has a respectable fan base of 5,000 fans, then they need $12.06 from every one of these fans in order to earn the federal minimum wage for four people, $60,320. In years past, they would sell their fans a CD. But now under the Big Pool they need an ungodly number of streams to make minimum wage: 8.6 million streams.

This means every single fan has to stream the band’s music 1,716 times. Assuming a four-minute song, that’s over 114 hours of listening, and if their fanbase averages 200 streams per month, then that means their fans would need to listen to the band 71 percent of the time for an entire year.

It’s like you bought a CD and the store told you that you had to listen to it 1,000 times, or they will give your money to Nickelback.

Subscriber Share only requires the fans to listen to the band 14.36 percent of the time, so if the typical fan averages 200 streams a month, then just 29 streams a month is sufficient, and the fan will only spend 22 hours in total listening to the band’s music. This is far more plausible for a new artist.

But intriguingly, Subscriber Share also enables fans to financially support an artist using even less effort: If a band can convince their 5,000 fans to listen to them exclusively for two months, the band will earn $70k, and the fans will only have to click once each month in order to do this.

Subscriber Share enables listeners to directly support the artists they care about without having to expend extraordinary amounts of energy to do so.

The result of Subscriber Share is that each and every fan winds up being far more valuable to artists. It honors the intent of the listener, and incentivizes getting more fans, bringing the goals of everyone (services, labels, artists and fans) into alignment.

If you think about it, this is how most of the genres we love got started in the first place. Hip hop, jazz, blues, reggae, punk, grunge, etc, all came from a small group of musicians and a small group of fans supporting each other. Who was the biggest beneficiary of this in the end? The music industry.

What are we waiting for?

It boils down to two big obstacles: fear and inertia.

To be fair, the music industry has been on the wrong end of the economic stick for well over a decade now, and talking about changing royalty methods just as it seems like things are about to get better is understandably scary.

The other problem is inertia. Institutions hate change; it’s expensive and hard, and you have to rethink everything attached to that change. Inevitably various special interests will arise and fight for the status quo. It can be very tricky to overcome their objections.

So it is difficult for the music industry to change, even when they know it’s in their best interest. They are like a cat stuck in a tree. They got themselves up and can’t figure out how to get down.

If the industry is immobilized by fear,and can’t be persuaded to move in the right direction with logic, then one possible way to get them to get them out of the tree is to make it even scarier if they don’t move. In other words: We need to scare the cat out of the tree.

And that’s where our little hack comes in.

A silent protest this September

A critical aspect of streaming music services is that the services can’t tell if the volume is turned down. If the music is playing the “clicks” still count, even if no one is listening. This can be used to our advantage.

Normally a typical subscriber can’t keep up with heavy users, in part because many of these heavy users aren’t even individuals to begin with: they’re actually offices, hair salons, gyms, yoga studios, and restaurants. But if typical subscribers streamed music 24/7, and just turned the volume down when they weren’t listening, then maybe they could catch up.

The result of Subscriber Share is that each and every fan winds up being far more valuable to artists.

And if these silent protestors streamed strictly independent artists, major labels would have to worry about the value of their streams decreasing. That could be enough to persuade them to reconsider the use of the Big Pool method, and if the major labels jump out of the Big Pool tree, the rest of the music industry will follow.

Even a small number of people engaging in this silent protest will have a measurable impact: Just doing it for one day will double most people’s monthly consumption, and doing it for one week will result in more streams than a typical subscriber consumes in a year. But obviously the more the merrier.

So let’s throw the idea out there and see what happens: For the month of September, let’s stream indie bands 24/7 non-stop, with the volume turned down to zero.

Note: It’s recommended that you change your selected indie artist on a daily basis (or even better, use playlists with multiple artists), so that you aren’t mistaken as a bot by the services.

If this works the music industry will be forced make royalties fair(er) for all musicians and fans. If it fails a couple of indie bands will get a bigger check than usual. What have we got to lose by trying?

Sharky Laguana is the CEO and founder of Bandago, the father of two boys, and a ping-pong enthusiast. Laguana was previously the guitarist and songwriter for Creeper Lagoon.

This article was originally featured on Medium and reposted with permission.

Photo via Max Fleishman