You are probably not going to own an Oculus Rift anytime soon.

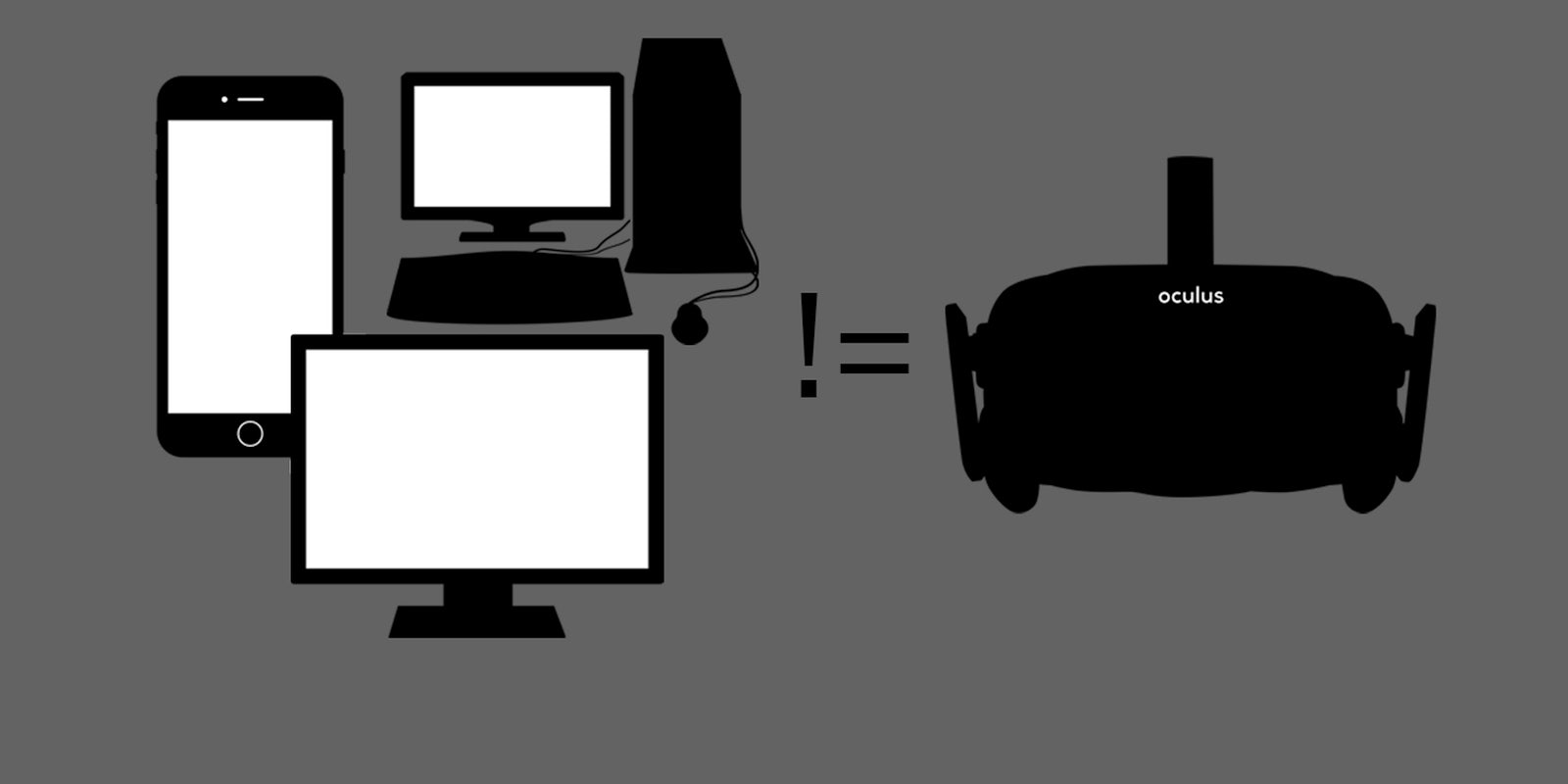

The sticker shock that spread across the Internet on Wednesday when Oculus finally revealed the $600 price tag of its flagship virtual reality product was silly. The asking price isn’t actually $600. You may have to tack on at least another $350 when you consider the cost of the single, basic upgrade to your PC that you might have to accept in order to run the Rift.

No one should have expected the Rift to be cheap, especially not when Oculus last year began advertising $1,500 bundles for a Rift-ready PC and the Rift hardware itself.

That Oculus founder Palmer Luckey created the impression in October that the Rift would cost around $350—something he apologized for yesterday—helps explain part of the shock, but the technical specifications have been published for a while now.

You need a GTX 970 or R9 290 graphics card to run the Rift, and either will cost you around $350 on NewEgg.com, which is how I arrived at the $1000, true price tag for the Rift. Those are powerful graphics cards that are way beyond what even a high-end gaming rig requires to handle demanding games at max settings.

The price isn’t the point, anyway. The question is whether and when virtual reality becomes the ubiquitous technology that Luckey wants it to be. For now, having seen the price of early adoption, we can reasonably say that common use of virtual reality effectively remains in the realm of science fiction.

Five years from now, the jury will be in on whether or not virtual reality will ever be more than the rich man’s toy it will be in 2016.

For anyone who’s bought into the promise of virtual reality, that it now officially retreats back into the realm of The Lawnmower Man is what’s so disappointing about a $1,000 price tag.

Unless you own a Samsung flagship phone, also an expensive proposition, and can therefore make use of the Gear VR headset, it’s officially time to take your dreams of enjoying VR on a regular basis and stick them back in the drawer.

If you think the Oculus Rift is expensive, wait until you see the price of the HTC Vive, the other, major PC-based virtual reality hardware on the horizon. Where the Oculus Rift is designed mostly for seated experiences, the Vive is designed for room-scale VR, i.e. getting up and walking around within a virtual reality simulation.

Oculus can sell the Oculus Touch handheld units separately from the Rift, because all you need to play Rift games is an Xbox controller, in most cases. The Vive requires a pair of base stations at the corners of the room, to read the available space and give you a visual prompt within the simulations so that you don’t walk into the walls.

The Vive also requires a pair of handheld controllers, because using a control pad while standing up really doesn’t work. If the Oculus Rift costs $600 for the headset alone, I wouldn’t be surprised if the Vive setup costs upwards of $1,000.

Counter-reaction to the Oculus sticker shock has mostly fallen along the lines of “Of course the Rift is expensive. What new technology isn’t expensive upon release?” And comparisons to PCs, smartphones, and high definition televisions ensue. None of those are good comparisons for the Rift. The best way to understand the situation is by looking at Tesla.

Tesla’s Model S car has zero emissions. It doesn’t require a drop of gasoline. The Model S is what every forward-thinking person who cares about climate change ought to want in their garage. Elon Musk is hailed as a visionary who’s delivered a new technology that could revolutionize the way we live on this planet. Tesla is the future.

Sound familiar?

The cheapest Model S I could find on the Tesla website costs $75,000, which is why Tesla automobiles are mostly a toy for the wealthy, and not the world-changing innovation they could be. No one actually needs a Tesla, not when you can buy a Toyota Camry hybrid for less than half the price of a Model S.

No one really needs a high-definition television, or a smartphone, or a high-powered personal computer, either. These are also toys for the wealthy. If you disagree, I suggest that you don’t have a grip on just how fortunate we in the United States are to live in a developed nation.

The seeds of demand for these products however, were planted decades before HDTVs, iPhones, or powerful laptops hit the marketplace. Motorola introduced the first handheld mobile phone, those huge, white, blocky things, in the early 1970s. The ubiquity of television sets began taking shape in the 1950s, which is the same decade that IBM began laying the groundwork for personal computers, by making the computer a popular tool for science and industry.

Even with the way computer technology advances so rapidly today, it might be another five years before middle class consumers can afford to buy a virtual reality rig, just to see what the technology is like.

It wasn’t until smartphones were made cheap enough for middle class, non-enthusiast consumers to purchase that they achieved ubiquity.

The court of public opinion also moves more quickly than ever before. Five years from now, the jury will be in on whether or not virtual reality will ever be more than the rich man’s toy it will be in 2016. Virtual reality could become affordable and still be nothing more than a futurist’s dream, because the public will have lost interest.

I’m certainly disappointed that my exposure to the Rift will for the time being continue to be limited to developer events like the Game Developers Conference and Oculus Connect, or to consumer-facing events like the Electronic Entertainment Expo.

Those events feed my curiosity as a technology reporter and video game enthusiast. As someone who enjoys learning about the challenges of game design, understanding the specific concerns of virtual reality software design is enthralling. But the average consumer doesn’t always get that experience.

As a reporter on the video game beat, I am shown game demos in controlled conditions at industry events, slices of the game experience carefully coiffed and manicured to give me the best possible experience with the game in the hope that I’ll write something positive that helps marketers sell the game to consumers.

Virtual reality demos have been consistently different from game demos in that the VR tech is rough, and developers make no attempts to hide that. That’s why seeing how VR operates in the real world, where no one is controlling the demo environment, is so important. No one can really gauge the effectiveness and value of virtual reality, until this happens.

The other issue with comparing the Oculus Rift to a smartphone is that most people don’t pay the sticker price for their smartphone. An iPhone 6 costs upwards of $550. A Samsung 6 might cost even more than that. No one other than enthusiasts likely pay these prices, however, because for most people their smartphones are subsidized as part of signing a cell service contract.

It wasn’t until smartphones were made cheap enough for middle class, non-enthusiast consumers to purchase that they achieved ubiquity. Oculus, and other VR companies desperately need to get their technology out of the hands of enthusiasts and into the hands of “regular people” in order to establish the value proposition of the product.

Getting virtual reality into the hands of non-enthusiasts is immensely important because the opinion of an enthusiast is always suspect, and I think anyone willing to drop $600 on a piece of hardware untested in the consumer arena constitutes an enthusiast.

Of course someone who dropped $600 on an Oculus Rift is going to want you to be excited about the technology. Your excitement, consciously or not, validates the enthusiast’s interests.

I distrusted interest in virtual reality, and Oculus specifically, for years until I’d had a bevy of experiences with VR tech in my capacity as a reporter. The average person doesn’t get that sort of opportunity. Yet, VR truly is the sort of thing you have to try, to understand. That’s a big hurdle for any new form of technology.

This is the other reason why smartphones achieved success, because people understood what a phone is, and what a computer is, and touchscreens aren’t difficult to wrap your head around, so a combination of all three makes sense.

But to slap a $1,000 price tag on a thing that most consumers can’t understand because they’ve never tried it?

“VR. Cool idea, bro,” says the consumer. “Let me know when I can afford one. Then I’ll start giving a damn.”

Dennis Scimeca writes for the Daily Dot’s Geek section.

Illustration by Jason Reed