On top of acting in no less than 14 upcoming movies, James Franco is a notorious celebrity queerbaiter—and he’s just upped the stakes. According a profile this week in the New York Times, Franco lives with a man—actor Scott Haze, who recently appeared in Franco’s Cormac McCarthy adaptation, Child of God. Could Haze be his boyfriend? The speculation has been rampant—surely James Franco wouldn’t need a roommate to help cover the rent or wouldn’t choose to live with a friend for companionship. So is he closeted? Is he heterosexual? Bisexual? It’s anyone’s guess at this point.

Franco has long played on the idea of the “bromance,” same-gender relationships that toe the line between homosocial and romantic; it seems like every time he comes out with something new to titillate the public, we have to have this conversation, and every time, it’s oddly unsatisfying. Franco is fully aware of our collective head-scratching—and he absolutely loves trading on it, whether he’s dressing in drag, posting selfies in bed with Keegan Allen, starring as himself in films where his co-stars make endless jokes about his sexuality, or making comments about possibly, maybe being gay. (By the way, this isn’t the first time a profile has mentioned him living with a man.)

In the Times profile, we’re told that Franco and Haze have been friends for ten-odd years, and that their friendship is something “more” than a friendship, that they enjoy a certain closeness and intensity that transcends those boundaries. The coded language here suggests that they’re gay, especially within the strictures of a heterosexual world that has difficulty when it comes to conceptualizing deep, emotional relationships between two men that aren’t actually sexual or amorous in nature.

Franco has trafficked on this kind of ambiguity throughout his career—both in his personal and professional life. He wants people to ask these questions and wants to be targeted directly with them so he can be evasive in interviews. In 2011, the actor told Entertainment Weekly, “There are lots of other reasons to be interested in gay characters than wanting myself to go out and have sex with guys,” without ever outright denying he’s gay. His work straddles that sweet divide of possibly maybe being queer enough to be embraced by the queer community (and lauded by “progressive” straights), but not being so queer as to offend the homophobes. He dangles the prize in front of his followers, and they’re left forever chasing the brass ring, not realizing that he’s made his actual sexuality almost beside the point.

He started to hit his stride in 2008 with Milk, when people wondered why a straight man was making a film about a gay icon. The film attracted attention on the awards circuit, garnering a Golden Globe nomination and marking him as a “serious” actor to watch. The former Freaks and Geeks star had finally made it. But more than that, it put him on the landscape as a man oddly fascinated and intrigued by queer sexuality, and it spurred discussion about Franco’s own sexuality. After all, some of the creator’s heart must go into the work, right?

Milk could have ended up being a fluke, but he didn’t stop there. Howl (2010), The Broken Tower (2011), Sal (2011), and Interior. Leather Bar. (2013) all played heavily on themes of gay sexuality, suggesting that this was more than a passing phase for Franco. Someone with that many queer film credits has to have something going on, right?

In Howl, Franco stars as a tormented Allen Ginsberg in a highly experimental film focusing on the San Francisco renaissance and Ginsberg’s obscenity trial. The Broken Tower, Franco’s film school Master’s thesis, may have been a critical disaster but it put Franco front and center as doomed poet Hart Crane, who committed suicide at 32 after struggling with his sexuality throughout his life. Then Franco directed Sal, examining the last hours of a gay trailblazer, Sal Mineo. Interior. Leather Bar. is a bizarre piece of docufiction that one critic said made it hard to tell if Franco was “flirting or kidding” with gay audiences.

In an interview with Playboy (I only read it for the articles), Franco said that:

Between World War I and World War II, straight guys could have sex with other guys and still be perceived as straight as long as they acted masculine. Whether you were considered a ‘fairy’ or a ‘queer’ back then wasn’t based on sexual acts so much as outward behavior. Into the 1950s, 1960s and so on, the straight and gay thing came up based on your sexual partner. Because of those labels, you do it once and you’re gay, so you get fewer guys who are kind of in the middle zone. It sounds as though I’m advocating for an ambiguous zone or something, but I’m just interested in the way perception changes behavior.

Uh, okay. That sounds a lot like Franco enjoys teasing his audiences and calling it art. And by not being explicitly gay, James Franco gets rewarded by Hollywood for his daring allyship, without running the risks of punishment for actually being gay. For someone like Rupert Everett, coming out means you stop getting hired, so much so that he discourages other gay actors from publicly disclosing their sexuality. For Franco, playing at gayness made him into an icon.

However, Franco’s hardly the first celebrity to traffic not just on nebulous sexuality, but specifically on titillating and teasing audiences with the possibility of queerness, without explicitly naming it. Hints of lesbianism or at least bisexuality, for example, are popular among pop stars like Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, One Direction, and the notorious Russian duo t.A.T.u, who made a career off making out in music videos and then denying that there was anything behind it. As t.A.t.u’s Lena Katina told the press, “It’s like, when you meet your friend, you can hug them, give them a kiss?…We never were lesbians, to be honest.” Baiting listeners moves albums and sparks press coverage, but in an essay for the Village Voice, Rich Juzwiak argues that it’s little more than pandering to a gay audience (while also, of course, tickling heteros).

Of course, these are singers first, not activists or sociologists. But even if we assume their sincerity, we can’t separate the message from the marketing, or the way their peddling interferes with the natural, less pandering-based gay sensibility. I’m speaking generally, and with awareness of the great variance of gay people’s interests, but to me, the beautiful burden of being gay forces you to search for your own heroes. To court us so visibly, explicitly, and successfully…is to take the connoisseurship out of gay taste, to sap the queer from queerness.

And, of course, shows like Sherlock, Once Upon a Time, Hannibal, Teen Wolf, and Rizzoli and Ives have all been accused of using queerbaiting to stir up audiences. Mostly notably, Supernatural spurs constant discussions about queerbaiting in pop culture versus actual queer representation—and largely put the term on the map in the first place. In a post for Autostraddle, blogger Rose Bridges explains,

When it’s that deliberate as in the cases of Sherlock or Rizzoli & Isles, there is a distinct feeling that the creators are playing with LGBTQ—and invested-in-LGBTQ-relationships (since the core of the “Johnlock” fanbase is slash-fanfiction-writing straight women)— dollars, but don’t care enough about us that they’d risk actually offending homophobes with explicit queer representation. Actors or writers may insist it’s not homophobic, but there is a distinct feeling that we’re being taken advantage of, that we’re second-class fans who they don’t care if they do a disservice to so as long as we still watch.

But despite the mixed reception in queer audiences, this continues to be a trend across the television landscape, so much such that TVTropes.org devotes an entire entry to “Sweeps Week Lesbian Kiss.” And when pop culture queerbaiting is so wildly successful, it’s not surprising that celebs are doing it, too.

In an ideal world, the answer to the are-they-or-aren’t-they question that queerbaiting provokes would be “who cares,” because sexual orientation should be something that people choose to engage with on an individual level, rather than needing to become a political statement. It should be something that just is, that doesn’t require deep, philosophical pondering, tabloid spreads, or Internet clickbait.

But unfortunately, we don’t live in an ideal world. We live in a world where people assume that everyone is heterosexual and monogamous until proved otherwise, where being an out celebrity is an act of bravery and defiance. Those who choose to come out are not just choosing to live openly with their sexuality, but are making a statement to society in general about assumptions, and breaking down stigma. For every queer celebrity who comes out, other queer folks can feel more courageous, and more accepted—it is a case where coming out is dangerous, but coming out also makes the world safer.

But what does queerbaiting really have to offer? It serves primarily to just further exoticize queer sexuality, and it’s frustrating to members of the queer community who are living out lives and facing the embedded dangers that come along with that—to those who live honestly and face the consequences. In an speech for the Human Rights Campaign earlier this year, Ellen Page addressed just how important an issue this is. “I feel a personal obligation and a social responsibility,” the actress said in a widely lauded coming out speech. “I also do it selfishly, because I’m tired of hiding. And I’m tired of lying by omission. I suffered for years because I was scared to be out. My spirit suffered, my mental health suffered, and my relationships suffered. And I’m standing here today, with all of you, on the other side of that pain.”

It might be a game to James Franco, but it’s deadly serious for the rest of us.

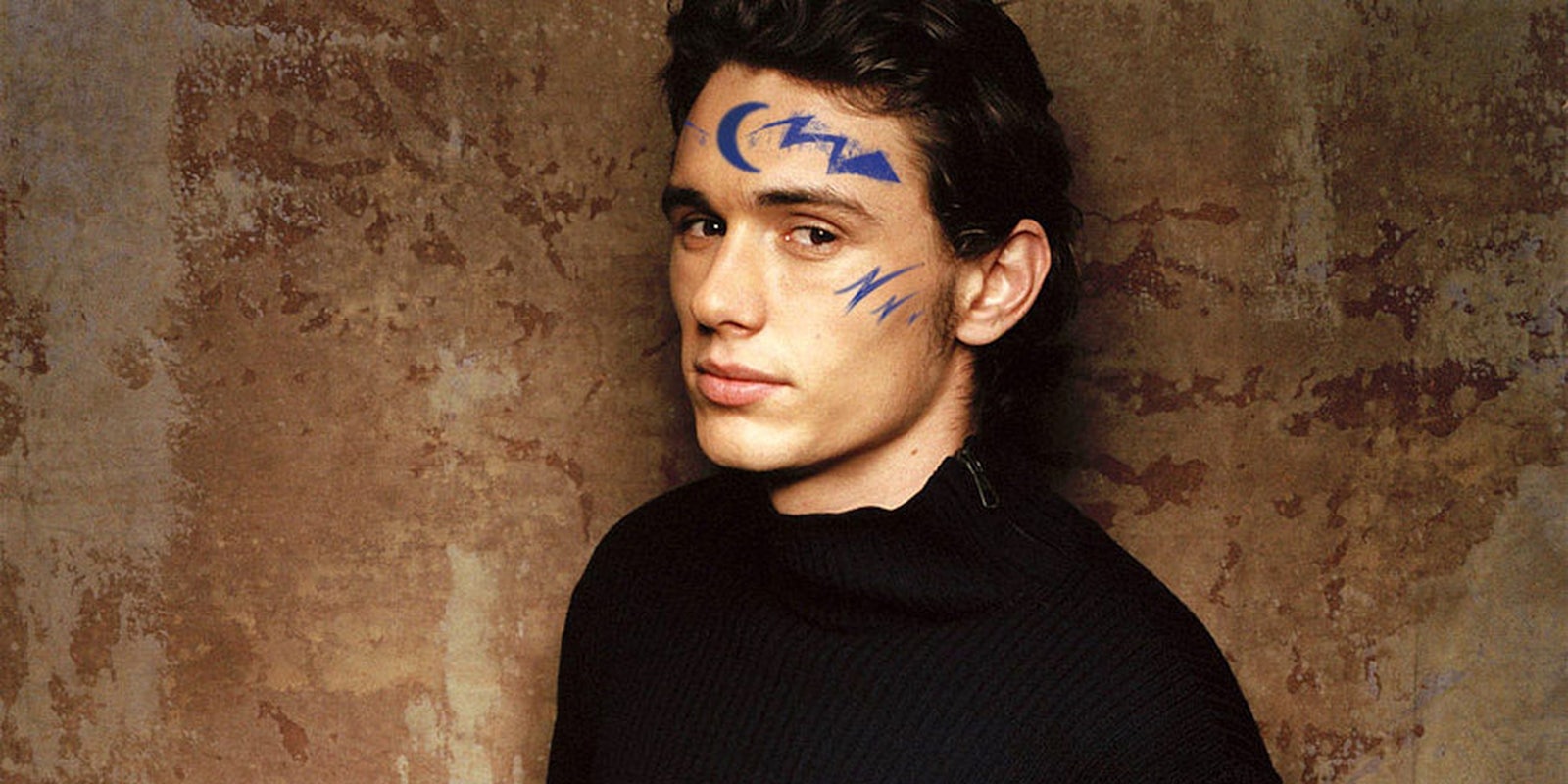

Photo via JulieKml1092/DeviantArt