BY IMAN HASAN

Warning: This article contains spoilers for season 3 of Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black.

I’ve been a huge fan of Orange Is the New Black since its first season debuted two summers ago, so naturally I binge-watched all of season 3 in one day. This season in no way compared to the last two—several plotlines were introduced and then dropped without any real conclusion, and by the finale, I didn’t feel like the show had moved forward at all—but its tenth episode particularly resonated with me.

This episode sees Tiffany “Pennsatucky” Doggett developing a relationship with one of the new corrections officers while they’re assigned van duty, amidst flashbacks that show a young Doggett having sex with her classmates in exchange for gifts and experiencing her first love. The episode ends with two back-to-back rape scenes: a flashback of a classmate forcing himself on Doggett at a house party, followed by CO Coates raping Doggett in the back of the van in the present day. Each time, the camera zooms in on Doggett’s face, focusing on her silent, defeated expression.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njy0dFFlpAc

It’s hard to pinpoint when rape became such a common plot point for female characters, but I think we can all agree that at this point, regardless of its intent, it’s overused. Criticisms of the way sexual assault is portrayed in popular media are equally abundant now that the topic of rape culture is creeping its way into mainstream awareness.

But we’re now past the point of thinkpieces that ask, “Is rape overused as a plot device?” We already know—the answer is yes. Now it’s time to dig a little deeper and ask, “How can rape be portrayed sensibly? Does it need to be present at all?”

But we’re now past the point of thinkpieces that ask, “Is rape overused as a plot device?” We already know—the answer is yes.

As rape is an issue that largely affects women, it makes sense that television writers include it in stories about women. What’s rarely considered, however, is who benefits from or is hurt by depictions of rape. It’s been argued that not depicting rape erases violence that women (and people of other genders) live in constant fear of, but do women want to be exposed to that violence in the media they peruse? And if done correctly, showing rape from a victim’s perspective could even be used as an educational tool for men, but is it worth traumatizing a female audience in the hope that a man might benefit?

The main problem here is that the predominantly male showrunners guilty of overusing this trope aren’t really giving this much consideration. The most relevant example I can provide is Game of Thrones, which used to be everyone’s favorite show but is quickly falling out of favor for its gratuitous gendered violence. Sansa’s rape, whatever the showrunners’ excuse for including it, was clearly meant to elicit a shocked reaction. It was a careless, sensationalist depiction of violence which wasn’t even in the show’s source material.

In addition, the scene wasn’t really even about Sansa. As Ramsey pushes her down and forces himself on her, the camera pans away and focuses in on Theon’s pained reaction.

By contrast, the rape scenes in Orange Is the New Black kept the focus and empathy on the victim. For the sake of full disclosure, I was triggered by the last scene. As I watched the look on Doggett’s face, I was reminded of my own rape and the feelings of helplessness and self-blame that characterized my experience. It was unpleasant to watch, and even less pleasant to be taken back to that moment in my life—but when I recovered, I realized this was not your average rape scene.

Whatever its intent, it wasn’t meant to shock. This was written by a woman, for women. It may have fallen into the trap of using the trauma of rape to humanize a character (“Rape is the new Dead Parents,” according to TV Tropes), especially as this season sees Doggett transition from a caricatured right-wing conservative villain to a likable character with an interesting context. But whichever lens you choose to view it through, it can’t be denied that the writing was conscious.

If there’s anything women want from writers in regard to rape scenes—besides fewer rape scenes, or no rape scenes at all—it’s consciousness. The main problem we keep having with shows like Game of Thrones is their use of rape for shock value, without any consideration of the emotional, physical, or psychological effects it might have on an audience.

In short, rape has become the clickbait of television: It doesn’t matter who it hurts, as long as people are tuning in and talking about it. What does this say about the actual level of respect popular media has for survivors?

The scene wasn’t really even about Sansa. As Ramsey pushes her down and forces himself on her, the camera pans away and focuses in on Theon’s pained reaction.

In addition, who faces consequences for careless depictions of gendered violence? Game of Thrones remains one of the most-viewed shows on television, despite the controversy it creates with each new episode.

In his defense of the story’s gratuitous depictions of rape, George R. R. Martin has said it’s “fundamentally dishonest” not to portray sexual violence. But here’s the kicker—women are aware of sexual violence. We live in fear of it every day. We don’t need to be reminded of that fear every time we watch TV, and it’s honestly callous for male writers to assume that showing teenagers getting raped in a sensationalized medieval fantasy show is doing anything for anti-rape advocacy.

Overall, most problems with televised rape scenes would be solved if networks would take responsibility for the content they’re showing. Besides providing incentive for show writers to be thoughtful when including rape in storylines, networks should use trigger warnings to warn audiences before they see something that could potentially be traumatizing. Regardless of how consciously a rape scene is written, viewers should be able to opt out of viewing it.

We shouldn’t have to rely on circulated tweets and Tumblr posts that tell us which scenes to avoid. If Netflix and HBO truly respect their female audience, they could stand to warn us themselves.

Iman Hasan is a recent grad and an aspiring writer and graphic designer, with a passion for makeup, ceramics and culture criticism. She is currently based in West Virginia and can be reach atiman.hasan.jrl@gmail.com or @flyinglotas on Twitter.

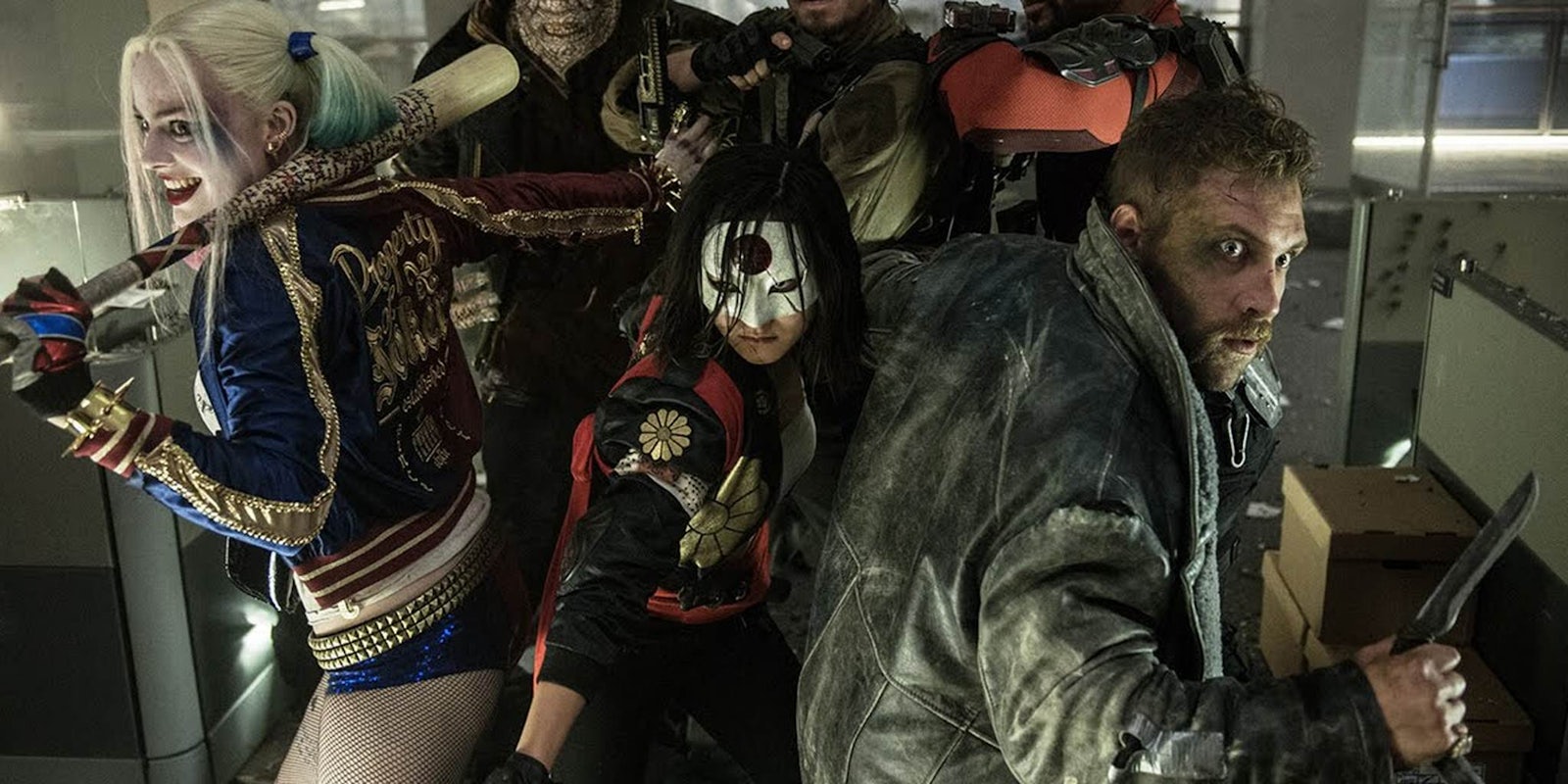

Screengrab via Netflix/YouTube