BY LOLA BAKARE

The moment I learned that the first female, black student body president of my elite, mostly white prep school was asked to resign, I instantly wanted to pick up the phone and tell someone they got this one dead wrong.

I wanted to look Dean of Students Nancy Thomas in the eye and ask her if we really live in a world where an ill-advised Instagram post has the power to end what should have been a year of triumph for Maya Peterson and the Lawrenceville community at large.

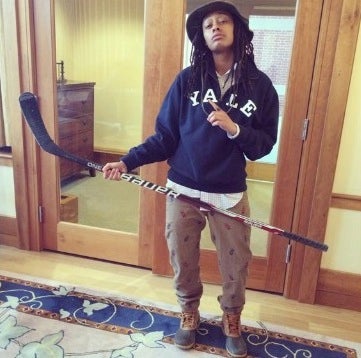

Photo via Instagram

The Lawrenceville School, a historic college preparatory boarding school founded in 1810, was home during my high school years. Its idyllic campus, stately architecture and lawns of technicolor green sits neatly between Princeton and Trenton in New Jersey—about an hour’s drive from both Manhattan and Philadelphia.

On a boarding school campus, the many growing pains of adolescence are magnified by the constant proximity of one’s classmates and the intensely competitive culture that encourages excellence in all pursuits, those academic, athletic, and otherwise. This pressure cooker lifestyle breeds excellence but can have its pitfalls.

As such, student life is nurtured by the careful attention of staff and administration to ensure each student gets the support he or she needs to succeed. Like Maya Peterson, I navigated Lawrenceville while both female and black, and the reassurance that I had a safe place to thrive, lead, and question authority set me on a lifelong journey toward self-acceptance, rooted in the promise that the inner struggle with my ever-present “otherness” was one I could win.

While Peterson’s mission as student-body president was to “make Lawrenceville a truly unified and diverse place,” the Instagram post that ended her tenure marked the end of lengthy smear campaign from some of her classmates, proving that the very unification she set out to cultivate was lacking more than she may have imagined.

In the post, adorned by hashtags #Lawrencevilleboi, #romney2016, and #peakedinhighschool, she is pictured in a Yale sweatshirt carrying a hockey stick, a pose mocking what Peterson herself called “right-wing, confederate-flag hanging, openly misogynistic Lawrentians.” Though numerous reports allege that the photo was a response to complaints about her senior yearbook photo, in which she and friends gathered with fists in the air, demonstrating the archetypal “black power” pose, Peterson told MSBNC’s Melissa Harris-Perry in a recent interview that the photo was meant to “put a satirical spin on something that [she] felt was an issue,” even if it was “not the smartest thing to do.”

Though arguably controversial, both Peterson’s senior photo and her satirical Instagram post were no more so than the confederate flag that hung in the room of one of my southern classmates when I was in school. When I asked this classmate why he owned a confederate flag, he explained that it was a symbol of southern pride. (We agreed to disagree on the appropriateness of this and later went on to become good friends.)

Though I agree that Maya Peterson’s Instagram post was a poor choice, given the context, the punishment she received did not fit the crime. Lawrenceville’s history clearly predicted the challenges that preceded the incident and proactive action could have eased tensions between Peterson and some members of the student body. There was tumult whenblack students were first admitted in the 1960s, there was tumult when women were first admitted in 1987, and as we learn in reports currently swirling the Internet, and there was certainly tumult when the first black, female, and openly lesbian student-body president was elected to her post in 2013.

Even before her detractors began their calculated smear campaign, the need for institutional support should have been clear when the very possibility of a fair election resulting in Maya Peterson’s rightful place in office was brought into question.

Instead of interpreting this for what it was, a sign of irrational incredulity in the face of change, the administration reacted by releasing voting data an action counter to the honor code that is part of the lifeblood of the school. Submitting to this request validated and likely fired up Peterson’s detractors while disrespecting both her honor and that of the majority of the student body which voted her into office. If voting results have never been published at Lawrenceville, this certainly was not the year to start.

Then, as is the fashion of the Internet Age, resistance to Maya Peterson’s presidency played out on the stage of social media. I won’t pretend to have all the facts, but if there are even kernels of truth in Buzzfeed’s recent reporting, Peterson’s privacy was continuously violated by peers who on more than one occasion shared anonymous “evidence” of her illegitimacy with school officials. According to an article in The Lawrence, Lawrenceville’s school paper, these early claims included everything from a photo of her smoking marijuana to what were later proven to be fabricated tweets designed to portray Peterson harassing a fellow student.

Though I applaud Dean of Students Nancy Thomas for making it clear that “she would not take disciplinary action based on information that was sent [to her] anonymously” and acknowledging the likely malicious intent of these anonymous whistleblowers, more should have been done to unpack the underlying issues that led to this during Peterson’s tenure.

If this continues, as Dean Thomas rightly acknowledged, we face a future where social media becomes an effective way to systematically remove those who demonstrate otherness in a way that traditional Lawrenceville finds unacceptable. Who is more likely to be protected by peers in the face of a debatably controversial Instagram post? Someone who represents the white male Lawrenceville tradition or a black female lesbian whose presence alone engenders the resentment of a powerful few?

When the Instagram post that would become her fall from grace was shared with the administration in March, it did more than just mark Peterson’s failure to complete her term. It also marked a victory for those who set out to knock her back down to her rightful place in student society. It was vindication for those who believed what a rising senior named Rob told Buzzfeed: “There was too much controversy around Maya…It isn’t a representation of who we are.”

In 2002, I staged a digital protest in the form of an all-school email after the fourth and final Martin Luther King Jr. Day that I would spend on campus passed unceremoniously—with no formal recognition of the day. I remember channeling my feelings of frustration and voicelessness into the then novel platform of an all-school email, sharing my belief in the need for change without mincing words. The following year, Lawrenceville began a new tradition, marking MLK Day with an school-wide day of service.

My hope today is that as a community, Lawrenceville students, alums, and administration will do more to support the Maya Petersons of the future. We can and must do a better job of fulfilling the school’s mission to “inspire and educate promising young people from diverse backgrounds for responsible leadership, personal fulfillment, and enthusiastic participation in the world.”

Like her namesake, whom we lost this spring, I have no doubt that Maya Peterson will continue to rise, despite what she experienced as student-body president of my beloved alma mater. Until Lawrenceville becomes a place where graduates continue to rise not in spite of, but because of their experiences on campus, that will have to be enough.

Lola Bakare is brand marketing director at The Daily Dot and attended Lawrenceville from 1998-2002. While there, she was active on student council, serving as president of Stanley house her junior year and Reynolds house her senior year.

Photo via Instagram