Last week the Internet was so busy fighting Suey Park that everyone completely forgot about the Redskins.

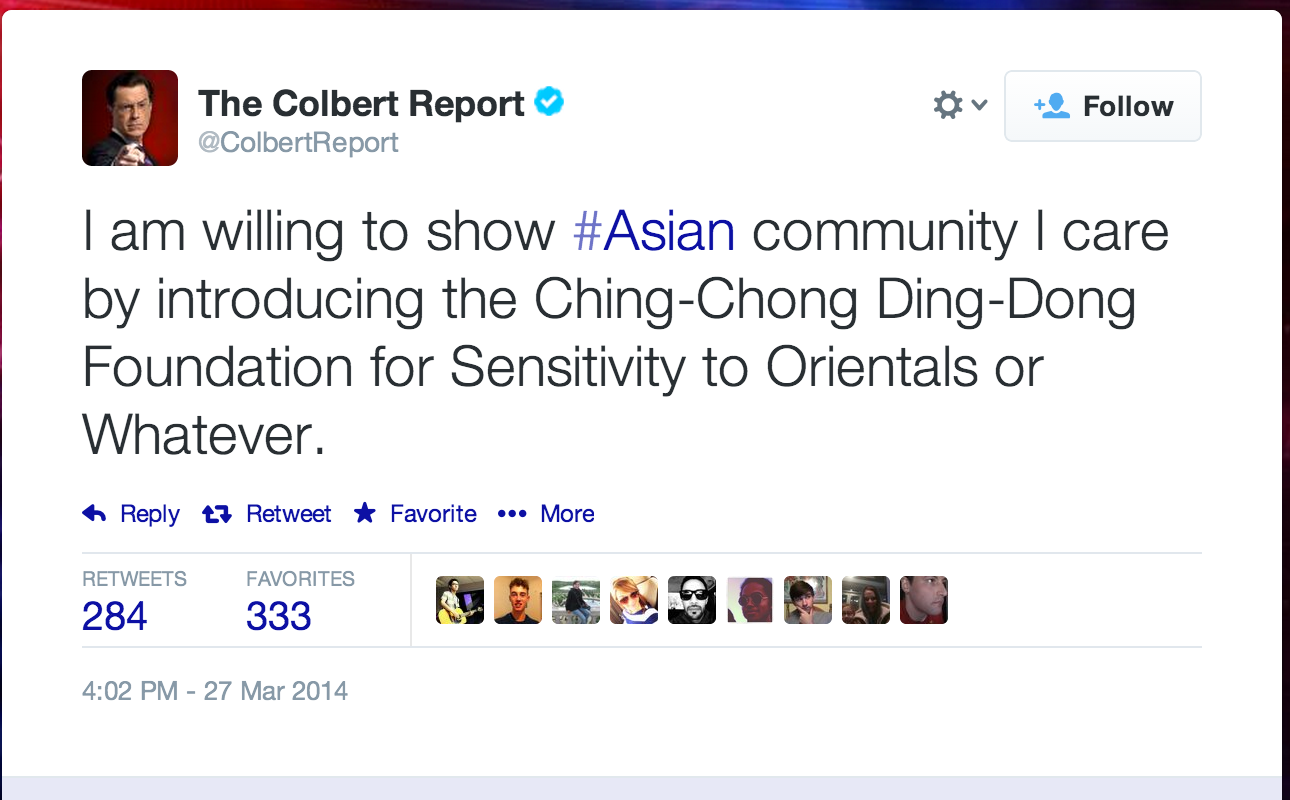

If you’ve been living under a media rock, let me catch you up. On Thursday night, The Colbert Report tweeted a punchline taken out of context from the show. The tweet targeted Washington Redskins owner Dan Snyder’s half-hearted attempts to placate the sustained critique of his team’s blatantly racist name. Ever clueless, Snyder started a charity for Native Americans called “Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation,” displaying the very term critics want him to retire.

On Stephen Colbert’s show, the faux-conservative host likened the name to the “Ching Chong Ding Dong Foundation for Sensitivity to Orientals or Whatever.”

The tweet quickly took off on social media, signaling a response from Suey Park, the well-known Twitter activist behind #NotYourAsianSidekick. Park’s concern was that the joke made Asian-Americans the butt of its humor, and to organize a response, Ms. Park created the hashtag #CancelColbert. In the same evening that the show’s tweet went out, #CancelColbert gave Asian-Americans and their allies a tool to discuss the ongoing marginalization of Asians in the media.

Rather than recognize those feelings as valid or use the moment to discuss systemic racism, Park’s critics latched onto that idea: offense. What was once a thoughtful discussion became a reduced to a group of people trying to take the Internet’s fun away. People were more concerned about defending a joke than making women of color feel welcome or included in the discussion, and that backlash quickly turned on Park.

Twitter users suggested that the real solution would be to #CancelSueyPark or take away her First Amendment rights. Others suggested corrective rape, a Twitter catch-all solution for when women (especially women of color) express critical, unpopular or controversial views. Jezebel writer Lindy West has discussed how her critiques of rape culture led to widespread threats of sexual violence against her. When women speak out, we’ve seen the same response time and time again. Offended, their male peers often resist a productive conversation and work instead to make sure women are silenced.

Anyone familiar with Twitter could have predicted this kind of gutcheck abuse, but the media hasn’t been welcoming either. Huffington Post Live host Josh Zepps, usually an affable moderator, brought Park on his show seemingly to make an example out of her, muting her and talking over her. Zepps referred to her viewpoint as “stupid,” at one point asking her if she understood the point of satire. Park deftly shot back, “Of course I understand satire. I’m a writer.”

Suey Park was clearly prepared for this kind of treatment and dismissal from the media. She’s got to be getting used to it.

Earlier in the year, CNN’s Don Lemon invited Ms. Park on to discuss the #HowIMetYourRacism hashtag, after CBS’s How I Met Your Mother aired a kung-fu tribute that featured the cast in kimonos, fu manchus, and yellowface. But, rather than starting a conversation about the continuing presence of anti-Asian racism on television, Lemon’s point was to show how “people are so sensitive these days.”

In the segment, CNN’s Tom Foreman remarks that “entertainment has long exploited Asian stereotypes for laughs,” from Sixteen Candles’ Long Duk Dong to Mr. Chow in The Hangover. But that point is dismissed, along with Park. Park is on air for all of 20 seconds.

The lack of seriousness with which Park’s criticisms have been taken speaks to the widespread acceptance of Asian racism in the media and larger society today. It’s not just about Colbert’s tweet, a joke that a) would piss less people off if it were at all likely that there was a strong Asian presence in the writers’ room, and b) would have been hard to make about any other community.

Jokes like these happen all the time and rarely anyone bats an eye. Seth MacFarlane’s show Dads ignored widespread criticism from Asian-American watchdog organizations regarding stereotypical “small penis” and “sexy schoolgirl” jokes. Fox rewarded MacFarlane with yet another season. CBS’s Two Broke Girls routinely makes its only Asian character into a Mickey Rooney facsimile (only missing buck teeth and a gong) and is one of the most popular shows on television.

Where’s the outrage? Where’s #CancelTwoBrokeGirls? When Duck Dynasty star Phil Robertson expressed homophobic views in GQ, equating homosexuality to beastiality, the media came for his head. Paula Deen lost her job over her love of the N-word.

But in 2006, Rosie O’Donnell used a set of “ching-chongs” on The View to imitate Cantonese, and it drew wide laughter from the audience. Hardly anyone suggested that she lose her job over it, and her publicist responded to criticism from Asian-American groups with a coy shrug: “She’s a comedian in addition to being a talk show cohost. I certainly hope that one day they will be able to grasp her humor.”

Rosie O’Donnell isn’t the only person whose Asian racism is so apparently avant-garde it defies the understanding of lay people. A couple years ago after a New York Knicks victory led by Jeremy Lin, ESPN’s Jason Whitlock commented on this Twitter that “some lucky lady in New York is going to feel two inches of pain tonight.” The sports network also used the line “a chink in the armor” when referring to Lin—twice. It’s hard to imagine a major news channel even going there with any other group of people, let alone doing it a second time.

Statistics show that this bullying isn’t confined to entertainment. According to 2009 survey data from the Bullying Prevention Summit, Asian-American students are far more likely than any other group to report harassment at school, with 54 percent saying that they were “bullied in the classroom,” 16 percent higher than the next closest group. They were also three times more likely than any other ethnic group to report Internet harassment—with 62 percent alleging being victimized online.

If those reports are true, it looks like Suey Park might not be alone in seeing the dark side of the Internet. What’s particularly troubling about that reality is that social and new media have long been at the vanguard of Asian-American empowerment and visibility. According to statistics from Social Media Today, around 20 percent of Asian-Americans are logged into Twitter, and over half report visiting YouTube weekly.

The Wall Street Journal’s Jeff Yang commented that social media is Asian-Americans’ mainstream media, catapulting YouTube stars like David Choi and Sam Tsui to widespread success. Park’s own #NotYourAsianSidekick proved what a positive tool Twitter can be to make Asians part of the wider cultural conversation.

However, Asian-Americans continue to be made invisible, even in spaces that are thought to be welcoming. Lam calls the struggles they face “The Bamboo Ceiling,” a culture in which Southeast Asians account for some of America’s highest dropout rates, while approximately 25 percent of Koreans and 17 percent of Filipinos remain undocumented.

This is a burden that particularly affects women of color like Park, who face a “double glass ceiling.”

Although Chinese and Indian men earn a higher weekly wage than any other group in the country, Census data from 2000 showed their female counterparts earn a staggering 40 percent less. Hmong women earn an average of $389 per week, far below the national average. They are joined by the Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians, all of whom counter the “model minority” myth of being high earners.

Being the model minority is an insidious idea. Although it seems like a nice stamp of approval, an embrace of the American melting pot, Racialicious’ Lindsey Yoo comments that it “effectively de-legitimizes [Asian-American] voices in conversations about promoting racial justice. “Leaving our voices and experiences out of the fight for racial justice erases our long, often tragic history in this country and homogenizes all Asians into one, high-achieving blob,” Yoo writes. “If you choose not to include us in discussions on racial justice, you are telling us that our struggles don’t matter.”

And the evidence shows that Asians are often left out of these conversations. In an article for The Rumpus, Matthew Salesses explains that when it comes to race relations, the “rules… are different for Asian-Americans.” For a living, Salesses organizes seminars at Harvard on the subject of inequality in America. He says that Asians have been brought up exactly twice in these lectures—and once from a student question. In response to Salesses’s assertion that “Asians don’t exist in Sociology,” Lindsey Yoo relates that she once pointed out to her Sociology professor out that statistics on Asians were missing in the day’s lecture, which compared parenting styles by race. Her professor responded: “The Asian perspective can be found in the stats on white people.”

John Ridley suggested that Asians are the new “Invisible Man,” commenting that they are “there but not there.” This will hardly change as long as Asian-Americans continue to be forced out of conversations that they should be leading. A culture of bullying and invisibility doesn’t just drown out dissenting voices like Suey Park’s. It makes it less likely that others will be willing to speak up in the future, simply because they feel like they won’t be heard. We will create a culture where Asian-Americans continue to be underrepresented in media and entertainment, perpetuating the very erasure that Park is fighting against.

During her HuffPost Live interview, Zepps asked Suey Park why she isn’t more concerned with criticizing the Washington Redskins, and she mentioned that she does have a background on Native American activism from her undergrad, where she fought on the same issues. The response was the same then as it has been with #CancelColbert: people just wanted her to shut up already.

Her critics might drown out the issue, but as long as their goal is silence, no one will win the debate.

Photo via Flickr/expertinfantry (CC BY 2.0)