How to Get Away with Murder is turning out to be a runaway success, counting 20.3 million viewers during its premiere episode; this includes the largest DVR numbers in history—adding over six million viewers to those who watched live. It’s not just trouncing this season’s competition: It’s breaking television records. We may have reached a tipping point for women of color on the small screen, behind the camera, and in production offices with shows like Scandal and Murder dominating viewerships and Internet discourse.

Scandal, Murder’s lead-in, netted 14.34 million viewers for its premiere this season, and even more flocked to Murder, clocking an 18 percent increase and justifying the decision to pair the two shows in a devastating 1-2 punch of politics and legal drama. The Internet blew up over both programs, with Murder co-producer Pete Nowalk perhaps putting it best:

Thank you to everyone who watched last night. Holy moly you guys shut Twitter down. Til next week! #HowToGetAwayWithMurder #HTGAWM

— Pete Nowalk (@petenowa) September 26, 2014

Nowalk speaks to the growing follow on social media in regards to both shows, taking them out of the cult category and making them into bonafide pop culture phenomena. You can’t open Twitter on a Thursday night without being deluged in Scandal tweets, and even if you aren’t watching live (in which case you’re better off closing Twitter to avoid spoilers) or following the show, you probably know what Fitz, Mellie, and Olivia are up to.

That Twitter success might have been built up over the course of Scandal, but the built-in audience took it, ran with it, and picked up new followers with the airing of How to Get Away with Murder, turning the show into a megahit right out of the gate on social media in addition to television. Rhimes has figured out how to leverage the shows she works on into social media hits, the secret to television success—and these two shows are likely to become a far more important part of her legacy than long-running Grey’s Anatomy and the more short-lived Private Practice.

The Internet has built a massive, incredibly loyal fan base, and it’s creating the propulsion needed to bring women of color out of the background in Hollywood and to the fore: Rhimes is an indisputable power producer and there’s a reason ABC takes her seriously enough to be running not one but three of her shows simultaneously this season. The Internet also doesn’t mess around when it comes to pushing back, hard, on offensive commentary and stereotyping of women of color in television, like People’s rude tweet (later retracted) about Viola Davis.

While the New York Times gave full credit for Murder to Shonda Rhimes in their infamous “angry black woman” article, Rhimes knows where credit for the show’s success is due: To the man who came up with the idea and brought it to her for mentoring and suggestions, and she wasn’t shy about saying so.

Confused why @nytimes critic doesn’t know identity of CREATOR of show she’s reviewing. @petenowa did u know u were “an angry black woman”?

— shonda rhimes (@shondarhimes) September 19, 2014

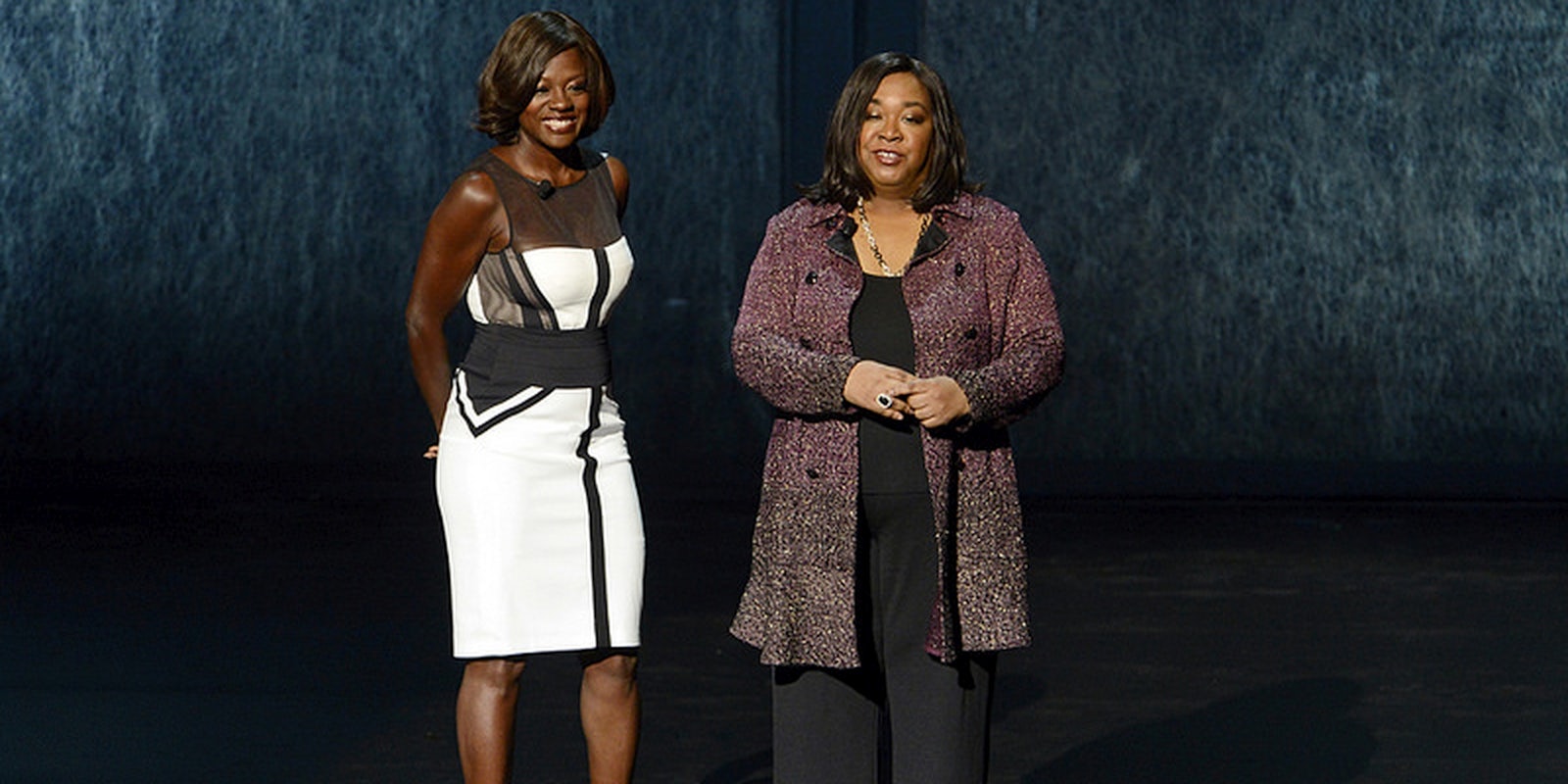

Her decision to pick it up with her production company, Shondaland, appears to be paying off. Fundamentally, How to Get Away with Murder is good television, especially with Viola Davis as a star vehicle; it was a smart artistic investment for Rhimes. Like other shows produced under the Shondaland umbrella, it’s also getting a great deal of attention for the diversity of its casting: We now have two strong black female leads to watch back to back on Thursday nights, when not that long ago, we had none.

With The Mindy Project airing on Tuesday nights and Rhimes’ dominating block on ABC on Thursdays, one wonders if this is, perhaps, the time for women of color showrunners and creators.

Not so fast, Charing Ball argues at Madame Noir. She points to the current surge in diverse television as a trend that’s more about shows produced primarily for white people by white people, skirting important issues of race. She points out that there is a “weird sort of segregation” in forcing black creators to bear the brunt of the burden when it comes to representing diversity, and that networks seeking praise take advantage of shows like these to showcase their progressiveness without actually taking action behind the camera and on production teams to create a more diverse working landscape.

In this version of Hollywood, a softpedaled version of race relations may trick white audiences into believing that television is more racially diverse and groundbreaking than ever before, but we’re a long way from equality on television, let alone anywhere else. Even as Kaling and Rhimes dance around racial issues on their shows, they rarely confront them head-on—and as women of color, they’re expected to be responsible for all the racial representation on television, while their white counterparts get a pass as long as they throw in a token cast member of color.

We should keep tuning in for How to Get Away with Murder and demanding more shows like it, but we shouldn’t be expecting people of color to do all the work. White creators and crews are just as capable of researching and depicting people of color and exploring racial issues, and they should exercise that ability to truly improve diversity on television; because it should be quite clear to studios right now that audiences are ready for it.

The Internet clamor over each new Rhimes production only seems to increase, along with ratings, and that suggests that there’s an important cultural phenomenon occurring here, one which networks can seize and take advantage of, or turn away from. Audiences clearly don’t just want diversity on screen, but also in the writers’ room, and at least some also recognize the importance of bringing people of color into the technical aspects of production, from lighting to costumes to cinematography. We may be at the tipping point for women of color on television, and in the industry, but it’s critical to remember that tipping points can go either way.

It might be easy to push television over the edge and into a world where race is represented more broadly, critically, and assertively on television, but it’s just as easy to slide back, too. As creators like Rhimes mentor up-and-coming talent and work to build a more diverse television landscape by promoting those who build diversity into the core of their projects, they’re still facing significant prejudice and discrimination.

After all, if the New York Times can call you “an angry black woman,” fail to do basic fact-checking on a show you’re involved in, and not even appear sorry for it until the Internet has called it to task vociferously and mercilessly, it’s safe to say that you’re not quite living in the Year of the Black Woman.

Photo via Disney | ABC Television Group/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)