It’s a truth universally acknowledged that a potential franchise in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a good white man. From Indiana Jones to Star Wars, white men have long been blockbusters’ bread and butter, our Ethan Hunts and Mavericks, our John McClanes and Terminators. They are the ones who save the world from the brink of disaster, whether the threat comes in the form of mutated dinosaurs, errant boulders, Nazis, or space evil.

Jaws, the 1975 mega-hit that created the tentpole blockbuster as we know it today, is the story of white guys saving the world from a shark. It’s the most obvious forebear to Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla, except this time (spoiler alert), the giant monster is the good guy. What’s most widely remembered about Jaws is Steven Spielberg’s decision to tell and not show, delaying the appearance of the titular sea beast as long as possible. Spielberg understood the power of building suspense, first grounding your story in a sense of character and stakes.

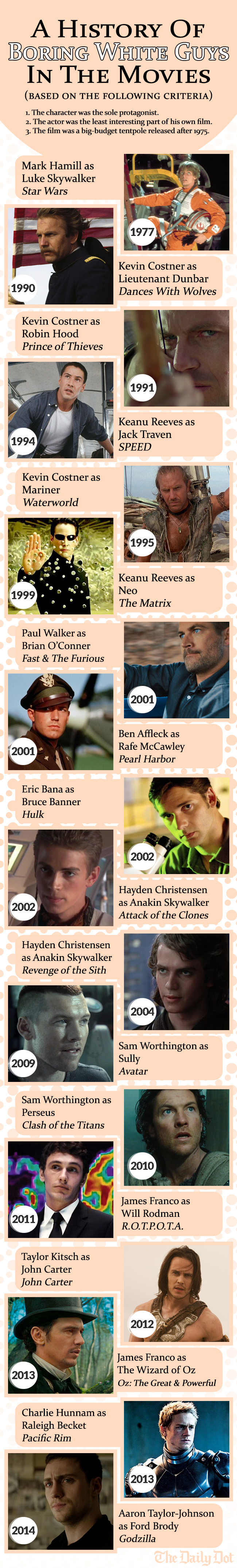

But in the case of Godzilla, we need saving not from giant lizards or jurassic moths, but from white men themselves.

To make Godzilla, Edwards brought together a dream cast of beloved character actors, including Juliette Binoche, Sally Hawkins, David Strathairn, Ken Watanabe, and Breaking Bad’s Bryan Cranston, who is proving to be one of the definitive actors of his generation. Bringing together this ensemble was part of the movie’s marketing strategy, a marker of the film’s quality. For those who remember Roland Emmerich’s previous attempt at bringing Japanese monsters to America, it was a sign the studio would totally fuck it up this time.

But the problem is that instead of making the film about its ludicrously talented cast, Godzilla hands off the narrative to Aaron Taylor-Johnson, a blandly pleasant-looking 23-year-old who seems to get less expressive with each film. Johnson has worked well in films where his blank slate personality fit the everyman nature of the part; whenever he’s asked to lend dramatic weight to the story, he fails miserably.

Taylor-Johnson plays Ford Brody, a character whose name appears to have been constructed as a masculinity Mad Lib—he might as well have been named Ken Doll McMilitary. Portraying a weapons specialist in the army, the British Taylor-Johnson approaches the character the same way, slurring most of his consonants to suggest Brando-esque reserve. Brody mostly comes off as practically brain-dead, and Taylor-Johnson’s pained attempts to emote were met with laughter from the audience I saw Godzilla with.

In Kick-Ass and Anna Karenina, most of the actual acting was wisely left to his female co-stars, Chloe Moretz and Keira Knightley, respectively. He just has to show up, which is basically what he does in Godzilla. But instead of being a supporting character in his own film (à la Kick-Ass), he is the entire film; during the third act, Godzilla drops most of its other characters, making the deadness at the core of the movie all the more pronounced. Cranston, likely a big draw for many in the audience, was barely in it at all.

Last year’s Pacific Rim shared a similar struggle, as it too insisted upon being about its least interesting character, another Vaguely Comatose White Savior. Its lead, Charlie Hunnam, adds little to the film except a glistening torso and a willingness to display it on-screen. His character’s only memorable moment is when he takes his shirt off. Otherwise Hunnam mostly proves his ability to stay awake and stare directly into the camera when asked. Hunnam can act, but you wouldn’t know it from the film, as he’s never asked to.

What proves most frustrating is that either film could have been about any other character. In Godzilla, Ken Watanabe and David Strathairn give credible (if too small) turns as a scientist and a general deciding the fate of the world, and Blue Jasmine’s Sally Hawkins stands around delivering expository dialogue, waiting for something else to do. Following the grand tradition of Disney movies, Juliette Binoche is just there to just to be a Fridge Mom.

Godzilla also casts indie sensation Elizabeth Olsen (robbed of an Oscar nod for Martha Marcy May Marlene) to play Brody’s wife, whose job is to stand around and look worried. Like Jennifer Connelly in The Hulk, she’s merely The Woman Who Cries, her face acting as a register for audience emotion. Despite Olsen’s clear skill at conveying shock and horror (what one might call “actual acting”), Godzilla never gets around to suggesting that she’s more than a narrative prop, a footnote in the story of some boring white guy.

But even when women are allowed to save the world, they’re still something of a side character and a curiosity, rather than an actual lead. Rinko Kikuchi became an audience favorite for her role in Pacific Rim as the tortured Mako Mori, a brilliant trainee fighting personal demons. The character’s inner turmoil, as seen in flashback, offers the film’s most powerful scenes, as she struggles with the memory of losing her family. There’s no reason that she (or Idris Elba‘s Stacker) shouldn’t be the center of the film, except that this isn’t the way things work.

Godzilla and Pacific Rim join a long list of Hollywood tentpoles who are about their least interesting characters—with examples spanning from Transformers’ Sam Witwicky and Avatar’s Sully to the titular wizard in Oz: the Great and Powerful. Was there a reason that 2 Fast 2 Furious should have become Brian’s story? Despite the late Paul Walker’s charms as an actor, Brian O’Connell was a cipher at best, a catalyst for action rather than a compelling protagonist. This is why future films in the franchise redacted this mistake, making him a small part of a Vin Diesel-led ensemble.

Having a Vaguely Comatose White Savior at the center of your movie isn’t always a bad thing. One of the great characters in movie history, Luke Skywalker, is the ur-type, but George Lucas and company knew how to build a movie around Mark Hamill’s limited expressive range. Sam Raimi got great mileage out of Tobey Maguire’s Benadryl style of acting, but even the best examples of the VGWS force us to ask uncomfortable questions. Where is the Miles Morales Spider-Man? Why is Hogwarts seen through Harry’s eyes and not Hermoine’s? Why can’t Morpheus the One?

In today’s marketplace, this is part of a shrewd marketing move, a calculation that audiences will only sign up if the movie is about a mostly mute white guy. For all of the graces of the Singer X-Men films, one of the main fan complaints is that the series continues to be about Wolverine, still the only character to get his own spin-off film. Whereas Wolverine was just one of the many in the comics, often overshadowed by Storm or Rogue, Hollywood made him into the star. It’s his show.

X-Men: Days of Future Past will prove an interesting litmus test, as the film’s marketing campaign increasingly foregrounds Jennifer Lawrence‘s Mystique. Although the teaser suggested that Wolverine again would be the lead, recent previews have banked off Lawrence’s widespread popularity (ahead of rumors that Mystique would get her own franchise). Days of Future Past debuts this weekend, and if its opening weekend is what prognosticators suggest (a whopping franchise-best $120 million), that figure will be as much a credit to Lawrence as it is to her movie.

There’s a reason that movies like Jaws and Star Wars worked, telling stories that filmmakers would want to borrow from and replicate. They weren’t just about white dudes but characters we could relate to and admire, ones that exist not in a post-human environment but a landscape that’s deeply relatable and inhabitable. It’s hard to see yourself in the picture if all you see is a white default screen.

Photo via Gage Skidmore/Flickr (CC BY SA-2.0)