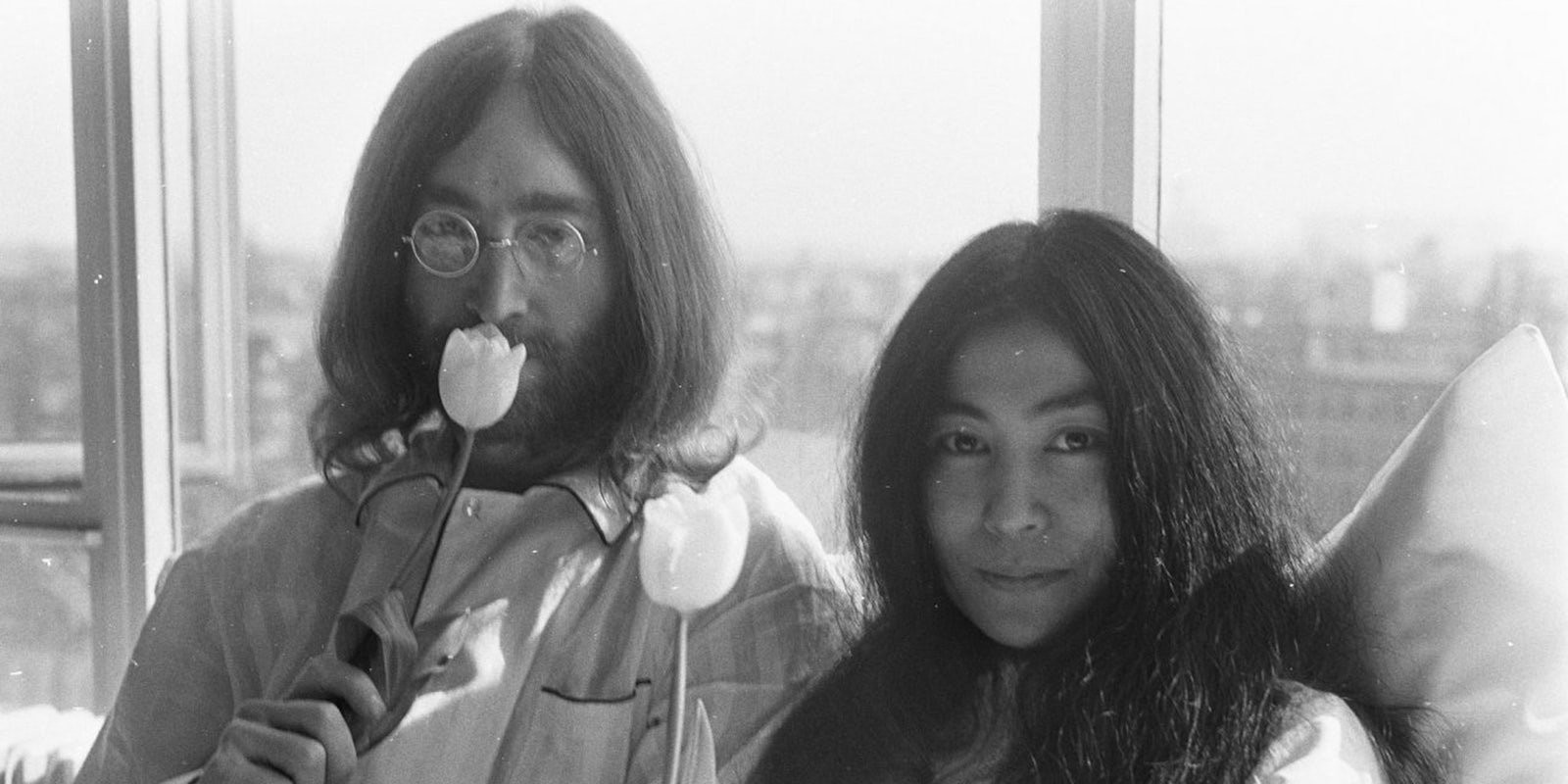

“Woman is the nigger of the world.”

Once upon a time, a very famous white man sang those words. His Japanese wife, an avant-garde artist, had coined the phrase in an interview a few years prior. The very famous white man recognized the phrase she’d casually uttered had great power. It compared and united in metaphor two struggling peoples—black folks and women.

When Yoko Ono and John Lennon were interviewed by Nova magazine in 1969, she used her extreme choice of language in a sort of offhanded way, like it was shorthand for a much larger idea of social injustice. She felt the comparison and presumed solidarity called attention to the plight of women. The phrase became a seed of thought and took root in John Lennon’s fertile mind. Years later, he wrote a song that used that phrase as the title, one that John and Yoko planned to use to gain attention for the feminist struggle. Two intelligent people, two brilliant minds, both convinced others would better understand sexism and the patriarchy if they compared women to “niggers.”

Of course, the word was more powerful than either John or Yoko anticipated. The backlash was enormous, and they quickly learned they’d made a colossal mistake. They’d confused both issues and helped neither.

If John and Yoko were anything as a couple, they were provocative. They were used to playing with the media to get their message out. They thought Yoko’s inflammatory phrase would call attention to the treatment of women. I mean, who thinks women should be treated like “niggers?” (What this phrase meant for black women was overlooked by both John and Yoko.) To them, it was a fire alarm ringing out in the deep of night. To most everyone else, it was more like they’d lit the fire. When lots of black people grew angry, the whole conversation about sexism derailed. No longer could John and Yoko focus the world’s attention on the mistreatment women faced. Instead Lennon made the rounds of an apology tour of the landscape of American media. The year was 1972.

“I believe in reincarnation,” John said, and Yoko bowed her head a little, curling up tighter next to him. “I believe that I have been black, been a Jew, been a woman; but even as a woman, you can make it.”

***

Forty-two years later and people still love to make similar ham-fisted comparisons. But I must warn you, using Yoko’s logic is a dangerous proposition. Even in 1969, the Nova interviewer made a prescient comment about Yoko’s tendencies of thought: “I think that eighty per cent of our life is based upon our mind, not our body,” she says with her great faith in the ability of percentages to lend weight, “so the imagination field is more important. By the time you are eighteen, your body is developed and your mind is left. It must be the mind because that’s all there is.”

Lazy comparisons and false metrics such as spontaneously invented percentages are often used as shortcuts to thinking. But, hey, I understand why Yoko and others would feel a desire to make such a seductive comparison. To many people, women and minorities often seem like the same thing. They look similar on paper, when considered and treated as statistics. They’re often treated alike by journalists and news organizations. In effect, women and minorities come across in our social discussion as practically interchangeable, like machine parts, two squeaky gears of society. It feels logical to use them like variables in an algebra equation wherein they can be swapped for each other to make sense of the unknown.

You will hear or read the phrase “women and minorities” in the news so often, it’s as if they were one umbrella demographic. There certainly are similarities to how we listen to them, how we see them, and what presumptions we make about them. Both groups face daily struggles to be taken seriously in a professional context, be it public or private. When they do speak up about the challenges they face, a privileged listener often fails to believe the degradation and abuses women and minorities know intimately. Evidence of this shows up in the words we use to describe their complaints: whereas a man is seen to be confident or assertive, a woman is bitchy or bossy, a black man is angry or uppity.

When you treat women and minorities as interchangeable social groups, any understanding you glean will only be true at the most superficial levels of analysis. As soon as you dig deeper and scratch past the boundary of skin, comparing social dynamics like sexism to racism won’t help you or anyone else understand either. Some things must be understood on their own terms. A prime example of this is rape culture.

I recently opened an essay with the line: “If you are a man, you are part of rape culture.” This one line and its implications seemed to offend some readers more than the persistence of rape itself. They were mostly men, and they felt victimized to even be associated with such an ugly word. To point out the injustice of someone regarding them as a potential rapist, their first and most common defense was to compare rape to racism. The offended parties commented, tweeted, and emailed me the same question:

“What if everyone decided to treat black men like potential murderers or thieves, the way women think men are all potential rapists?”

Such a reversal of values sounds logically useful. Both rape culture and racism are institutional problems. Both are motivated by fear and violence. Both are behaviors our society deems “wrong.” It seems like comparing the two is the perfect way to better understand two wildly destructive social ills. Plus, if we use this comparison, one can point out any logical flaws of such a sweeping and aggravating statement like “If you are a man you are part of rape culture” by asking if it would be fair to treat others in society the same way that rape culture suggests we treat women (and men).

Like, would it still be fair to ask a black man to change his behavior to make white people not feel threatened? Shouldn’t we judge a black man by the content of his character not the color of skin, and thus, shouldn’t we judge all men on their own merits and not by their gender?

Would you tell black men how to behave so they don’t frighten white people in public?

When you put it that way it sounds so obvious you want to say, “Oh, sure, bro, I see exactly what you mean. Being a black man, I wouldn’t want to change my behavior when white people are around just to make them feel comfortable and safe in my presence.”

But here’s the thing. I know what it’s like to be both a black man and a victim of sexual assault. And as such, I can tell you they’re not the same. I was at a party. I was intoxicated. A man found me, alone, passed out in a bedroom. I wasn’t penetrated, which means I can’t really say I was raped. The assault was interrupted by someone who walked into the room as it was happening. I woke to the feeling of beard bristle against my neck as the person pulled my pants up. Clearly, I’d been fondled and molested while I was passed out. I was still inebriated.

Confused and angry about what had just happened to me, I left the house and walked to a friend’s place. When I told him what I knew had happened, he did his best to take care of me, but frankly, he kinda freaked out because he didn’t know what to do. We were two young men in college. This wasn’t supposed to be the sort of a problem we had to deal with.

I was taken to a hospital. They performed a rape kit. If you’ve never had one, it’s a very demeaning, clinical, invasive procedure. It’s intended to collect evidence for the prosecution. They use tubes and flashlights to peer into your vagina/anus to look for tearing. They use ultraviolet light to detect semen residue. And when you’re done being poked and prodded, you’re often left alone for long stretches of time as you begin to process what just happened to you.

Of course, because I’m a man (and was assaulted by a man) talk quickly spread. Soon everyone I knew had heard the story. I left school for the last two months of the semester because it was so humiliating and difficult to deal with. Afterwards, I never feared for my safety when I was alone with a man. I didn’t worry when I passed out somewhere. But a part of me changed. This is why it’s very easy for me to see how the two are not the same at all. I know the effect of racism and our rape culture, firsthand.

There is no rational way to fully protect oneself from rape or sexual assault. You can’t be smart about it. You can’t rely on your physical toughness or ability to fight back. These are assumptions one makes but rape is not always a matter of being overpowered. Like me, one can be passed out when it happens. What then? What do you tell someone? Never sleep? Husbands rape wives, wives rape husbands. What do you tell them? Don’t go home and don’t go to sleep? Rape is not a matter of making bad decisions. Rape only requires two things: a rapist and a victim.

That said, let’s return to the question:

Would I ever recommend black men change their behavior so they don’t frighten white people?

Well, friends and neighbors, this question is actually fairly easy to answer since I am an American black man. I can and do counsel other black men about how to deal with scared white people. The only question I’m left wondering before I answer is: Am I giving a black man advice to help him deal with the fear of frightened white people, or am I telling him how to make the white people not feel so threatened?

This is a critical difference. When confronting rape culture, I offered advice to men, since I see them as victims and perpetrators of rape culture. If you are a man you are part of rape culture because you are a perpetrator of it and you are a victim of it. You are a victim because others might hold unfair and erroneous opinions of what kind of person you are just because you are a man. You are a perpetrator of it because until you understand it and work to fight it, you are part of the problem. As such, many women and men won’t trust you; they don’t feel they can interpret your intent, and thus, you remain a threat, like a wild animal in a city, or like any unknown that threatens humans.

How is that different from the black man who scares white people?

Well, first and foremost, there is no such thing as a black man. We invented the idea in the New World. Before slavery made black people, there were Africans. But in the New World, a new label was invented, one given to draw a distinct difference between the indentured servants and show why they were better off than the slaves they often lived with, ate with, married and started families with in the early days of the American colonies.

After a few servant-and-slave uprisings, such as Bacon’s Rebellion, the poor of colonial America were legally labeled as whites and blacks. One group was told they were free, while the other was told they were slaves. Since then we’ve accepted the idea that a black person and a white person are real things. They’re not. Any fear of either is a product of that same initial economic decision to separate the poor underclass. Racism is unfortunately real, but race is entirely imaginary.

Rape, on the other hand, is one of the horrors of reality. While early Americans may have created modern racism, rape existed long before we gave it a name. As many critics of rape culture like to point out, animals rape each other. This observation is a Nature-based rationalization that “boys will be boys.” It’s a defense of rape as a natural phenomenon. It excuses the behavior as an inescapable quality of life on Earth. But whether animals rape one another has no bearing on whether we rape one another. Just as we’ve evolved past a vast number of our lower impulses, jungle urges, and ugly primal behaviors, we can evolve to the point such an excuse holds no water. Oh, look, we’re here now!

Rape is a violent, willful act perpetrated by men and women, against men and women, and it can deform the lives of men and women. Regardless of how we interpret statistics or define our terms, we all agree: rape is a problem. To say all men are part of rape culture is not to say all men are rapists, or perpetrators of a crime, but that they are unfortunately cast in roles they wish not to play, they are unfairly labeled, and they are treated as both possible abusers and victims. Well, the same is true for women. Thus, everyone is part of rape culture.

When John Lennon and Yoko Ono sang about how “woman is the nigger of the world,” it wasn’t cool. It wasn’t smart. And it got away from them. Eventually, John Lennon had to appear in a cover story for the black culture magazine, Jet. The title was “Ex-Beatle Tells How Black Stars Changed His Life.” When we use race to explain something like rape culture, or sexism, the comparison fails for a few reasons, but mostly because the dynamics at work are so very different.

Racism is a byproduct of a history of greed, division, and the whims of economic power. Rapists and rape apologists rely on personal and social power. It’s not a byproduct but a willful act made possible and exacerbated by society. This is what makes it rape culture.

When one suggests all men consider the effects of their behavior in public spaces?—?specifically, asking them to be considerate of women—?it’s out of respect and consideration for others. It’s not a mandate, an edict or a fatwa. It’s not an appeal to submission but rather a call to decency.

Asking a black man to change his behavior so he doesn’t frighten white people extends the long shadow of economic racism. Black men don’t have the power in that situation, even though they are the source of fear. The black man may have the physical force to overpower you, but his power is singular, it is physical. The rapist’s power is quite different. In this case, the power is cultural. American history made the black man. American culture teaches the world to fear black men. But America doesn’t grant black men power—not the way our culture grants power to men. Asking any man to consider how he uses his social power is not the same as asking a black man not to scare white people. It’s not even close.

Women learn to fear men because our culture is based on male supremacy. Women see they have less power and that the power and influence of men more often determines the shape and direction of our society. It’s the same way that anyone can see how money buys justice. In such a system as ours, the crimes of a rapist are commonly excused, while the crime of rape is often dismissed or even defended. Meanwhile,the victims of sexual assault are marginalized, stigmatized and often blamed for their attack. Experience teaches women (and men) that in our culture, rape is expected, and sadly, too often it’s accepted. This is how and why our rape culture persists?—?spurred on by male supremacy.

If we wish to dismantle rape culture, it will require men to change. No matter how much black men change their behavior, they remain black men. They can’t dismantle the power and fear of racism because it’s not a power they wield. They are victims of the fear, as well as pawns in the economic legacies we inherited from the greed of colonial America. Now, even though race is not real, our social problem of racism, just like our social problem of rape culture, is very, very real. Other than that, if you wish to understand them, to compare rape culture to racism helps no one. It only makes you sound like John and Yoko—and I don’t think that’s the best way to win converts to your worldview.

Zaron Burnett III is a social commentator and humorous essayist. He lives in Los Angeles. This article was originally featured on Medium and reposted with permission.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons