By STEFFAN HEUER and PERNILLE TRANBERG

Search results can help predict flu outbreaks. Location data can prove that malaria spreads through human travel rather than mosquitos. Crime stats can help pinpoint which prison parolees are likely to commit murder. Piracy and terrorism can be prevented. Credit card and insurance fraud get caught in real time. Taxis can save fuel and not drive to the airport if there is a long line of other taxis already waiting for passengers. And companies can optimize their services and give us relevant recommendations.

We spend a lot of time in this column warning about encroachments on our privacy, but it’s true: big data—all the unstructured data online and on company servers—can do a lot of good and help us find and use convenient services, if the data sets are structured and treated properly. That’s the case in all the above examples.

We are at the brink of a new era in which data, generated by humans and connected devices large and small, becomes our new currency. And as with any valuable asset that people and organizations are eager to trade in and profit from, precaution is vital. Otherwise these resources will be plundered and monopolized by the robber barons of our time. Data will be smuggled and laundered to conceal its origin, fakes will circulate and hurt the entire economy. Ultimately, trust will fall victim to the widespread data rush.

We are at the brink of a new era in which data, generated by humans and connected devices large and small, becomes our new currency. And as with any valuable asset that people and organizations are eager to trade in and profit from, precaution is vital. Otherwise these resources will be plundered and monopolized by the robber barons of our time. Data will be smuggled and laundered to conceal its origin, fakes will circulate and hurt the entire economy. Ultimately, trust will fall victim to the widespread data rush.

And a data rush it is. The current environment reminds is reminiscent of an earlier rush some 160 years ago, when unsuspecting, credulous people—some indigent, some greedy explorers—rushed to the supposed gold mines. This new kind of gold rush, for data, is going on all around us, intensifying every day. What does that mean for the everyday user of web services and smartphone apps? The one giving the data away?

Big data can be used for good, or it can be abused and exploited. The players involved who are using our data need to be open and transparent about what they use the data for, and what they don’t use it for. Otherwise, we risk the modern-day equivalents of specious finds and scams, deadly landslides, and toxic sludge. As advocates for privacy and digital self-defense, we absolutely want to be a part of this emerging digital society, so we do entrust our information to various service providers we consider responsible: telcos, social media sites, banks and credit card companies, even some apps for our smartphones.

The emphasis, of course, is on the word “consider,” since every week we discover how companies and government entities are abusing and betraying our trust in them. Most providers can do much more when it comes to informing us what they do with our data: with whom they share it, from whom they buy additional data, how long they store it, and if they ever delete it—let alone revealing what treasures they have built on our trust.

***

A new report from from the World Economic Forum entitled ‘Unlocking the Value of Personal Data: From Collection to Usage’ looks to the issue of data governance. It compellingly concludes that we need a new approach—to stop focusing on protecting individuals from all possible risks, to instead identifying risks and facilitating responsible uses of personal data. Because, the report states, the failure to use data can also lead to bad outcomes.

The WEF report underlines that we still need security for our personal data against those organizations mining and using it. But we need to rethink key principles such as “notice and consent” and “single use.” This is because individuals play a role as both producers and consumers of data; because new and beneficial uses of data are often discovered long after it has been collected; and because the sheer volume of data being collected is staggering.

The report goes one step further. It says that the current approach to providing transparency through lengthy and complex legalistic privacy policies overwhelms individuals, rather than informs them. Yes, absolutely: scientists have estimated that it would take the average person 25 full work days to read just the legalese for the typical websites they visit in a year.

But the report points to a hopeful new trend. There are indications that a “data literacy movement” is beginning to emerge in North America and Europe—a movement which could help cultivate real understanding.

For example, certain companies are aiming to develop simple explanations of their approach to data use in plain language, so that an individual can quickly understand the main elements of how data is being used. The company Intuit has established and shared its “Data Stewardship Principles,” that are at the heart of how the company deals with personal data. This principles set out in clear, simple language what Intuit stands for, what it will do, and what it will not do. Intuit will not sell, publish or share data that identifies any person. But the company will use data to help customers improve their financial lives and to operate its business.

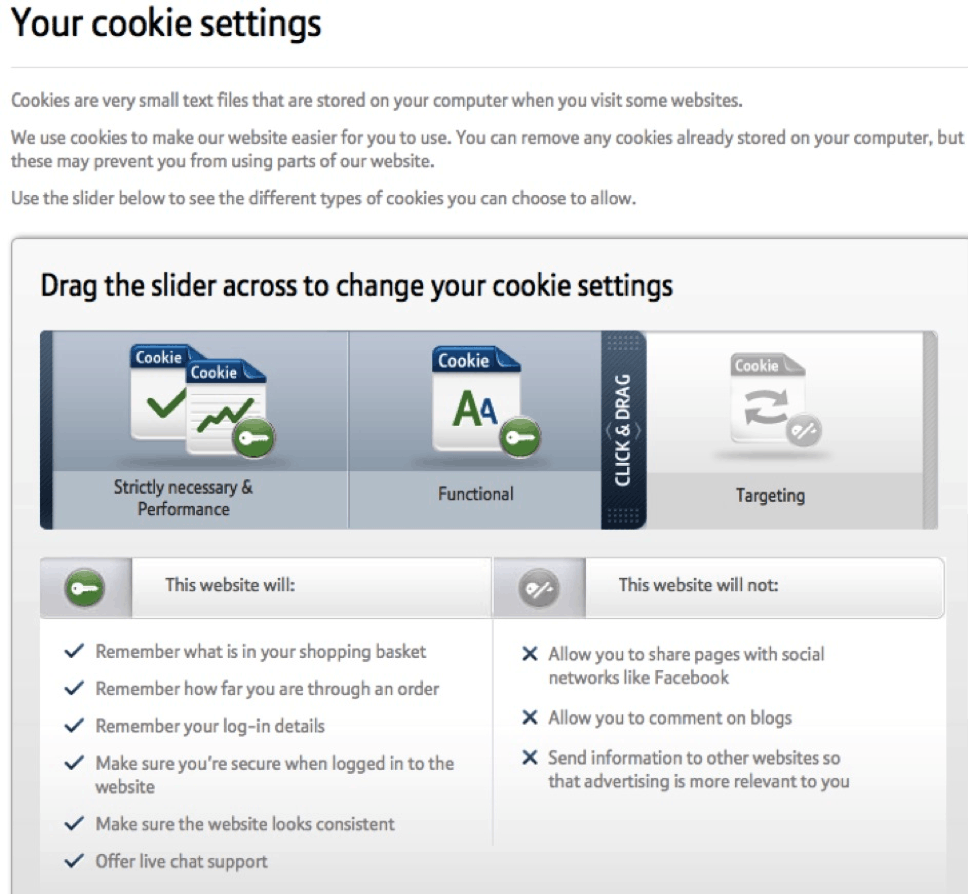

BT.com has also made movements in this direction, implementing the recent update to the EU e-privacy directive, the so called “cookie law.” The cookie law requires companies to obtain the consent of their website users before placing cookies on their computer. Whereas most companies put in place a pop-up box asking users to click to consent, BT implemented an clear, easy-to-understand practice for visitors to its website. A pop-up screen allows users to quickly see those cookies that are truly necessary for the site to operate properly.

Privacyscore is a tool helping to enable this new data literacy movement. It analyzes the privacy policies of companies along four clear criteria and gives each website a color-coded rating and score, from 0 to 100, with anything below 80 being in the dangerous red zone. An updated browser extension, Privacyfix, scans for privacy issues based on your Facebook and Google settings and takes you instantly to the settings that you need to fix.

Mozilla has proposed another tool to help us “read” privacy: a symbols-based guide to the presentation of legal terms in icons that signal, for example: how long data is retained; whether data is used by third parties; if and how data is shared with advertisers; and whether law enforcement can access the data.

This movement towards data literacy is very positive. Because in the end, it’s our job as consumers and citizens to hold companies and government entities accountable, and to demand they use our information in an open, transparent and responsible fashion. And if you can’t consider your web service or app responsible—if you harbor any doubts that they don’t use your data responsibly—there’s still the “delete my account” button.

Steffan Heuer and Pernille Tranberg are authors of the book Fake It: A Guide to Digital Self-Defense, just published in its second edition. They cover technology and privacy issues in San Francisco and Copenhagen. In this series, Digital self-defense, Heuer and Tranberg report with updates from the digital identity wars and teach us how to defend our privacy in the great data grab going on all around us. Follow them at @FakeIt_Book.

Photo by dvanzuijlekom/Flickr