It’s a familiar refrain to teens regularly being lectured about the dangers of posting compromising photos or messages online: “The Internet is forever.“

But perhaps that shouldn’t be the case according to a top European court, which ruled Tuesday that people can ask Google to remove links to sensitive information from its search results.

The ruling, from the European Union Court of Justice in Luxembourg, is seen as a major win for online privacy advocates who believe there should be a “right to be forgotten” on the Internet. However, not everyone is pleased with the decision, which could put a costly and time-consuming burden on tech companies and challenge free speech rights.

The court’s decision came in response to a case filed by a Spanish man, Mario Costeja González, after he sought unsuccessfully to remove an 1998 auction notice of his repossessed home from the website of a major newspaper in Catalonia. González’s is one of 180 similar complaints filed in Spanish courts requesting that Google delete personal information from its searches.

In their verdict, the judges ruled that after a person searches their name and comes upon sensitive personal information, they may approach the host of the information directly to try and have it removed. If the host website refuses, the court says the subject of the information can then “bring the matter before the competent authorities in order to obtain, under certain conditions, the removal of that link from the list of results.”

No doubt such a precedent will be seen as a godsend for people who’ve had unflattering information about themselves published in the police blotters and court dockets of countless newspapers. But Google says that a court forcing them to remove links to such information years after the fact amounts to censorship.

“This is a disappointing ruling for search engines and online publishers in general,” a statement from Google reads.

The ruling was also criticized by a number of European politicians and activists. British Justice Secretary Chris Grayling, an avowed critic of efforts to create a statutory “right to be forgotten,” said the court’s ruling could cost British business £360 million a year. He said the cost of going back and deleting vast sums of personal information from the Internet was disregarded in the ruling. Others have stated that, since it’s still legal to publish public information items like legal proceedings, it’s wrong to make search engines responsible for blocking that information after the fact.

Other’s say that this ruling goes too far in allowing people to change the past.

“The principle that you have a right to be forgotten is a laudable one, but it was never intended to be a way for people to rewrite history,” said Emma Carr, acting director of the privacy rights group Big Brother Watch, speaking to the Guardian. “Search engines do not host information and trying to get them to censor legal content from their results is the wrong approach. Information should be tackled at source, which in this case is a Spanish newspaper, otherwise we start getting into very dangerous territory.”

Still others champion the ruling, arguing that search engines and tech companies should be held responsible for the way they use and share people’s information. Former conservative British politician David Davis said the decision essentially gives people property rights over their own information.

“The presumption by Internet companies and others that they can use people’s personal information in any way they see fit is wrong, and can only happen because the legal framework in most states is still in the last century when it comes to property rights in personal information,” Davis said.

But what does this ruling mean for the United States? Obviously America does not fall under the jurisdiction of EU courts, but this ruling could spark a philosophical change in the way people around the world think about personal information in the Internet age.

In a 2012 article published in the Stanford Law Review, George Washington University Law Professor Jeffrey Rosen explains the key difference in how Americans and Europeans approach this issue. He says Americans’ highly-prized free speech rights make them less amenable to deletions of public record.

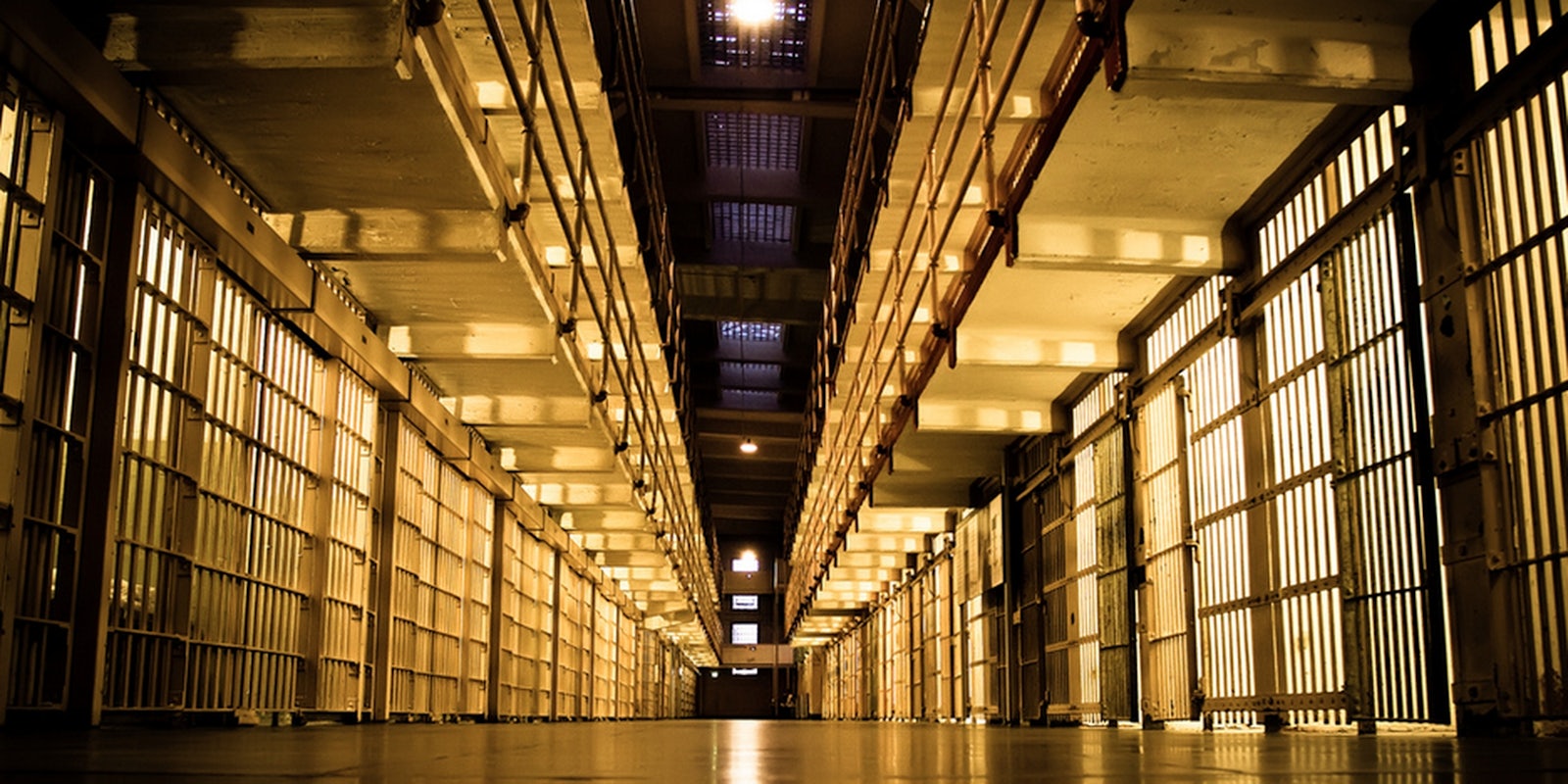

“In Europe, the intellectual roots of the right to be forgotten can be found in French law, which recognizes le droit à l’oubli – or the ‘right of oblivion’ – a right that allows a convicted criminal who has served his time and been rehabilitated to object to the publication of the facts of his conviction and incarceration. In America, by contrast, publication of someone’s criminal history is protected by the First Amendment, leading Wikipedia to resist the efforts by two Germans convicted of murdering a famous actor to remove their criminal history from the actor’s Wikipedia page.”

H/T: Reuters | Photo by Sean Hobson/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)