Opinion

How many things have you been asked to boycott since President Donald Trump took office?

Equinox, SoulCycle, Nordstrom’s, Home Depot, Wayfair; the hashtag resistance has been quick to fight back against Trump with its wallet by launching consumer boycotts.

But has it worked? The short answer is “no.”

In an interview, Brayden King, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management (whose work focuses on boycotts) told the Daily Dot:

“In reality, there is not a lot of evidence that consumers really boycott anything … The real reason that boycotts seem to be effective is they damage a company’s reputation … Often, companies will concede to activist demands simply because they want to get rid of that threat to their reputation.”

But upon closer examination, it is clear that social media boycotts are largely ineffective because online boycotts alone rarely extract concessions without a larger strategy in mind.

Groups that have successfully leveraged social media as part of a larger effort view online boycotts as one piece of a larger, sustained effort. Unions, migrant workers, and student activists have all successfully used boycotts as one piece of a broader strategy.

Meanwhile, pumping a hashtag doesn’t do much without sustained action behind it.

…

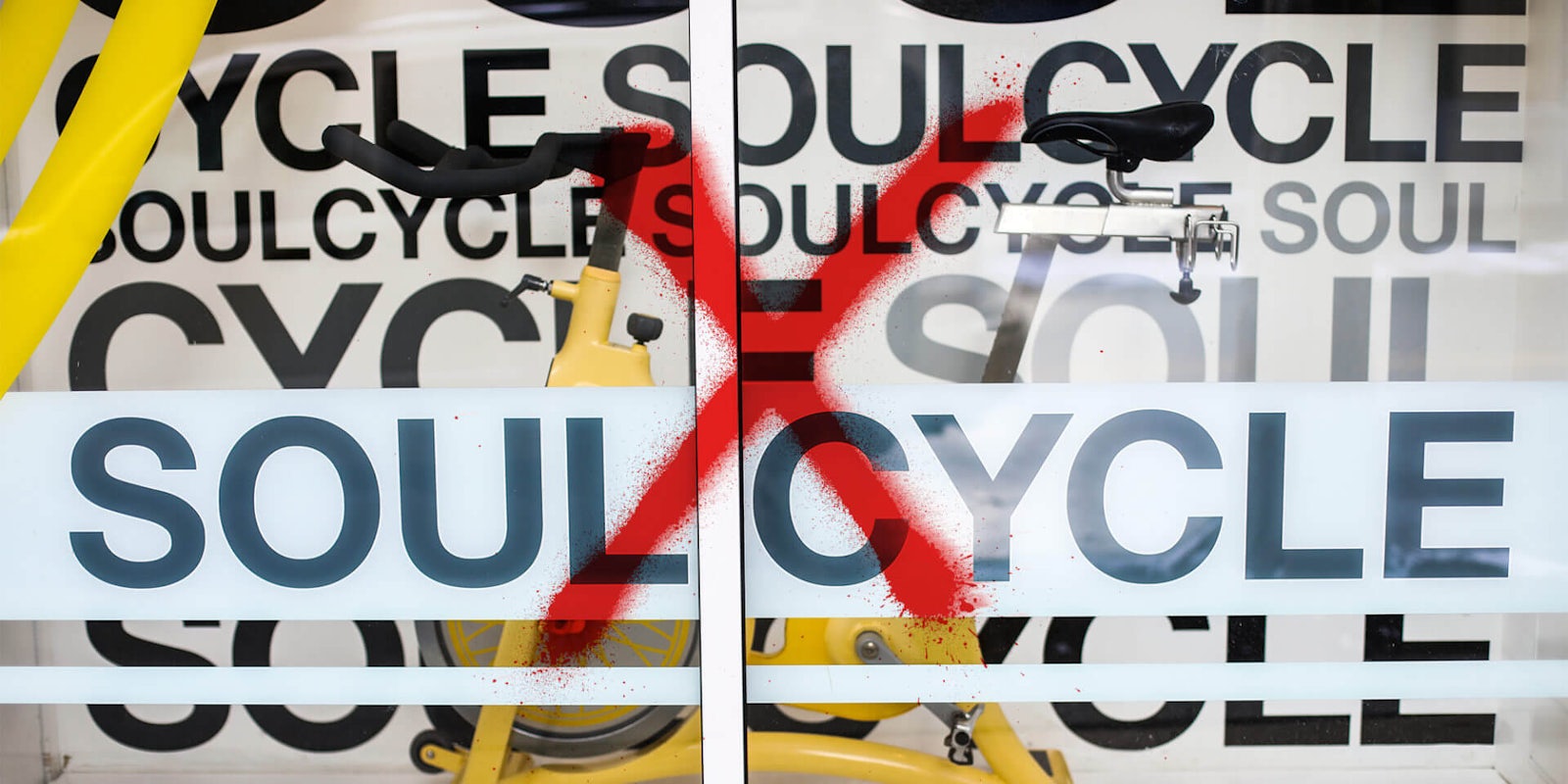

Last month, Equinox and SoulCycle became the next in a long line of businesses to draw public ire for their connections to Trump. Stephen Ross, the billionaire real estate developer, Miami Dolphins owner, and big-time Trump supporter is also an investor in SoulCycle and Equinox.

News that Ross was slated to hold a Trump fundraiser in the Hamptons with tickets ranging up to $250,000 per person led to a call to boycott both fitness brands. A social media-driven boycott led by celebrities with large follower counts ensued.

Just contacted @Equinox to cancel my membership after many years. Money talks, especially with these monsters. If it’s too inconvenient for u to trade one LUXURY GYM for another, then you should be ashamed. (No disrespect to the many wonderful employees at my local Equinox). Bye!

— billy eichner (@billyeichner) August 7, 2019

rough day at equinox pic.twitter.com/CNxrQUbpCQ

— chrissy teigen (@chrissyteigen) August 7, 2019

While the call for a boycott certainly got the internet’s attention, it’s too early to say if the boycott of Ross’ businesses will have a clear financial impact that will affect his decision to align with Trump. Riders canceled memberships; classes were canceled. But, it will take time to see if the boycott impacted the mogul’s bottom line.

The Atlantic noted that last month new sign-ups have been down, but whether this pressures Ross to change his politics is dubious at best.

There are, though, plenty of other test cases from the Trump era as consumer boycotts have become a hallmark of resistance. The results have been mixed.

During the 2016 general election, activist Shannon Coulter launched the #GrabYourWallet campaign, targeting Trump family-related clothing products. The boycott began as a reaction to Trump’s treatment of women, specifically, the public outrage in the wake of the Access Hollywood tape.

Famously, she took aim at Ivanka Trump’s clothing line. Ivanka, the movement contends, was complicit in her father’s campaign, presidency, and misogynistic behavior.

.@Nordstrom: as a woman, longtime customer, and huge fan of your brand, I’m concerned that you carry the Ivanka Trump collection. 1/

— Shannon Coulter (@shannoncoulter) October 12, 2016

Though the #GrabYourWallet campaign targeted a number of companies that carried Trump-branded clothing and products sold by Trump supporters, the most prominent targets were clothing companies Nordstroms, TJMaxx, Macy’s, and Marshall’s.

It’s hard to argue that the backlash against Ivanka Trump’s brand wasn’t successful, as the clothing line shuttered in 2018. Nordstrom’s, for its part, dropped the brand in early 2017.

However, it is difficult to determine if the boycott was the cause, or if the brand damage of Trump’s politics did the work on its own. In the midst of the boycott, in February 2017, Kellyanne Conway promoted the brand on Fox & Friends leading to massive, but temporary sales boosts. It also sparked tremendous backlash.

As brands removed Ivanka’s products from their stores, they simply blamed “poor sales.” Overall, the profits of these companies were not particularly impacted by the boycott.

Nordstrom Q4 2016 profits missed targets but analysts chalk this up to an industry-wide trend. Macy’s had a weak 2016, but not an especially weak Q4. TJX, which owns TJ Maxx and Marshall’s, had a great 2016, capping off the year with a 6% increase in revenue for the fourth quarter.

Other boycotts have had similarly mixed results. Last month, protesters called for a boycott of Home Depot following news that co-founder Bernie Marcus pledged to donate to Trump’s 2020 effort. The company’s stock price was largely unmoved by the boycott. Retailer Wayfair was the target of a boycott and a walkout initiated by the company’s workers after it was revealed that the company was a vendor for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in late June. The company took a financial hit in July, but this was attributed to a correction for bullish growth in previous months.

In reality, it’s hard to say whether these had an impact.

Professor King says, “I don’t think #GrabYourWallet is effective as a means to mobilize consumer support … I do think it likely had a long-term reputational effect on the companies that didn’t distance themselves from Trump.”

If these boycotts have had an impact, King says, it’s likely too soon to tell. He adds, “It’s quite possible that the boycotts are changing the ways investors, analysts, and employees think. While it may not have an impact on their short term sales … Only time will tell if it will have an effect in that way.”

King estimates that only a quarter of boycotts extract concessions from companies. He says that the true goal behind a boycott shouldn’t simply be to harm a company’s bottom line. A more desired result is that the company makes a positive change in response to negative attention.

Because for a boycott to be successful, it needs a clearer demand.

Barry Eidlin, assistant professor of sociology at McGill University says that “[These social media boycotts don’t work] because they are just about virtue signaling. They are not about actually trying to mobilize opposition and exert a sort of countervailing force to the corporations or to achieve any kind of broader political goal … It’s not something that can just be willed into being by a generalized sense of moral revulsion. It has to be a product of a campaign that has coordinated organization and a clear set of demands.”

It makes sense that a successful boycott would have to mobilize sustained opposition since the news cycle moves so quickly on social media. More successful efforts tend to sustain themselves beyond the day’s headlines.

For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Farm Workers’ (CIW) ongoing efforts to improve conditions for migrant farmworkers who supply tomatoes for fast-food restaurants has been effective. For decades, the group has pressured fast-food restaurants to sign on to their Fair Food Program, which involves a concrete list of commitments and demands.

A number of restaurants and food providers have signed, often under threat of boycott, including McDonald’s, Yum Brands, Burger King, Subway, Compass Group, Aramark, Sodexo, Whole Foods., Trader Joe’s, and Walmart.

These successes have allowed CIW to shift its focus to an aggressive campaign against Wendy’s, including a boycott of the fast-food chain.

These successes have had nothing to do with a hashtag, but with a collectively aligned, obtainable goal.

Another issue that both King and Eidlin spoke to was the need for organization. Social media-only campaigns tend to lack organizational structure. Eidlin says “I’m not aware of any instance where a boycott was the decisive factor in a campaign winning. It is always a part of a broader campaign that has a bunch of different tactics at work.”

Eidlin adds:

“We have seen in recent years that online organizing can actually work in some cases… like the teachers’ strike wave where the online platform provided some very useful tools to amplify the organizing happening on the ground. I don’t want to be completely dismissive of online hashtag activism. [But it only works] under very specific circumstances and almost invariably only when it’s anchored by actual on the ground person-to-person organizing.”

King makes a similar point. He says:

“The ideal boycott generates a lot of attention because that is what brings the reputation pressure against the firm, but it also has an infrastructure behind it. I think the ideal boycott is one that has a message that gets spread online but there is an NGO and a social movement group behind it that is carrying out the boycott as part of a larger strategy… I think the ideal boycott would have a combination of attention plus infrastructure in place to do something with all those resources you just created.”

Another group that is launching effective boycotts is Unite Here, a “union that represents 300,000 working people across Canada and the United States [whose] members work in the hotel, gaming, food service, manufacturing, textile, distribution, laundry, transportation, and airport industries.”

Unite Here has only grown in power during the Trump administration, becoming a serious political player in Democratic and left-wing politics. Part of its strategy is launching targeted boycotts of hotels where its workers are in contract disputes or have other workplace issues.

Maria Hernandez, communications director of Unite Here Local 11 in Los Angeles, issued a statement to the Daily Dot about their work and what makes an effective boycott:

“What sets Unite Here Local 11 apart from consumer boycotts like Soul Cycle in the Trump Era is that our boycotts are launched with the support of the workers of the boycotted company themselves and backing of the union. Having the support of the union gives workers a way to continue to hold companies accountable to do the right thing.”

Social media plays an important role in building support for a boycott. We’re in an era in which people want to be more aware of the ethical consequences of the decisions they make about where they spend their money. And people increasingly spend so much of their everyday lives—from paying bills to shopping to finding a hotel for a vacation or business trip—online. That makes social media an important crucial role as a platform to build support for a boycott.”

To discuss boycotts as “online” or “IRL” is a false division. An effective boycott will combine online messaging with other tactics and strategies that can feel old-fashioned. Without a broader strategy like that employed by Unite Here, a boycott will likely fail.

Trump-era boycotts have worked. But, not in the way, you might think.

And the most effective ones aren’t necessarily the ones trending on Twitter.

READ MORE: