Did Russia “hack” the U.S. election? Your answer to this question likely reveals where you stand on the political divide—or, perhaps, on the definition of the word “hack.”

Debate over the popular mantra that Russia “hacked the U.S. election” has percolated into the soggy upper echelons of American political discourse, bolstered by sharp chatter from supporters of President-elect Donald Trump who claim this assertion is patently ridiculous.

“The DNC was hacked. John Podesta was hacked. Russia did not ‘hack’ the 2016 presidential election,” or so the argument goes, from Twitter and Reddit to cable news. (Some, like former Trump advisor Steve Cortes, argue that even Podesta wasn’t “hacked,” but instead “gave into a phishing scheme.” More on that later.)

.@CortesSteve: “Podesta was not hacked. He gave into a phishing scheme…who falls for that?” #inners https://t.co/kGKSDovxr6

— All In with Chris Hayes (@allinwithchris) December 30, 2016

This assertion gained steam Thursday night after the FBI and Department of Homeland Security released a 13-page Joint Analysis Report (JAR) outlining why the U.S. intelligence community believes Moscow is to blame for hacks and leaks against the Democratic National Committee and Podesta, Hillary Clinton‘s 2016 campaign manager.

Russia, for the record, denies any involvement. And at least two independent security researchers agree that the JAR fails to provide conclusive evidence that Russian intelligence “hacked” the Democrats, regardless of whether it did. Far more evidence is needed, and much of that evidence likely remains classified (if you believe it exists).

Still, the JAR and the Obama administration’s aggressive sanctions on Russian intelligence agencies and officials and ejection of 35 Russian diplomats from U.S. soil make it more difficult to doubt, as Trump has, that Russia was behind the attacks against the Democrats. Without further information, we’re not going to solve the puzzle of whether Russia was behind these attacks, however. So, we’re left to debate whether “election hacking” is an accurate description of events.

Dear media, the election wasn’t hacked. The DNC was. Big difference. #FakeNews pic.twitter.com/YFJn7sfWj3

— Palmetto Joe (@Palmetto_Joe) December 29, 2016

The media is, I can only assume, largely to blame for popularizing the notion that Russia’s alleged hack of the Democrats and leak of hot-button emails constitutes an “election hack” or “election hacking.” Go ahead, Google it. You’ll see countless headlines—including plenty from the Daily Dot, most of which I probably wrote—using these phrases or something close to them.

So, is the media full of shit? Is it spreading “fake news,” or is it correct to say that Russia allegedly “hacked the U.S. election” and Trump supporters are just splitting hairs to keep their man from looking less legit?

Yes—all of the above.

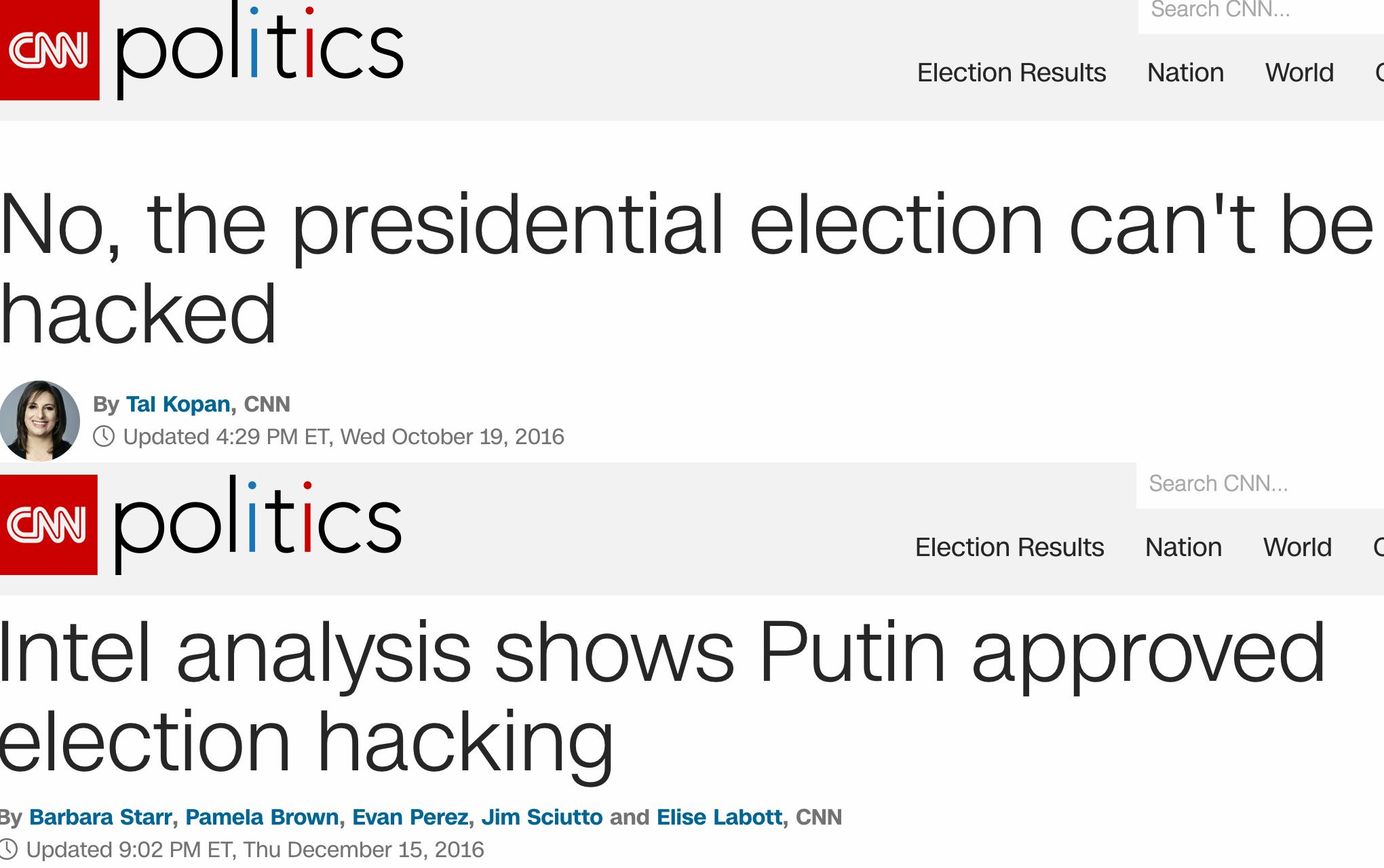

For many, the phrase “election hack” suggests tampering with voting machines to change ballots. Why would anyone think that? Well, for one, the media told them that’s what it meant. They, along with President Barack Obama and others, also told them hacking the U.S. election wasn’t possible (largely in the context of Trump claiming the election was “rigged”)… then told them Russia did exactly that.

The issue here is that “hacking” does not just mean breaching a computer system, tampering with code, or installing malware that steals sensitive data. “Hacking” also means social engineering—manipulating people, not machines. Russia is accused of doing both. (In fact, it’s accused of doing both at once—and then some.)

Now, strictly speaking, “hack” generally means manipulating code or machines or gaining access to a protected system, while “social engineering” means manipulating people to achieve a goal. But in practice, social engineering is a prominent hacker tool, and gaining access to protected systems is often possible only because of social engineering. “Humans are the weakest link in the security chain,” the infosec saying goes.

Many of the “hacks” you hear about—whether it’s a celebrity Twitter account hijacked by pranksters or Podesta handing his Gmail login over to Russian intelligence thanks to a spearphishing email—are accomplished through social engineering. Hell, even CIA Director John Brennan’s AOL account was hacked (by a 13-year-old) using social engineering, not some sophisticated code. It’s just part of the hacker’s toolbag, whether you’re a script kiddie or the goddamn GRU.

The “phishing scheme” Podesta and his staff fell for is just one part of what the media reports mean when they say Russia “hacked” the U.S. election. What the media mean in the current context is that, according to U.S. intelligence, Russia breached the DNC and Podesta’s Gmail through social engineering (i.e. convincing but bogus Gmail password-reset emails that gave Russian hackers the login credentials), stole a bunch of emails, leaked them to WikiLeaks and other websites, which then published the documents. This created a cache of records for the media to report on, which it did. Then, by keeping the Democrats’ dirt in the headlines, an air of scandal swayed enough American voters’ away from Clinton—who, confusing the matter further, was embroiled in a separate email scandal of her own—and toward Trump, who ultimately prevailed in the presidential election.

Of course, that doesn’t make a catchy headline.

There is data to support this theory of events, as convoluted as it sounds. A FiveThirtyEight analysis of polls leading up to Nov. 8 found that Clinton’s lead over Trump fell 18.5 percent (from seven points to 5.7 points) amid a deluge of WikiLeaks’ Podesta email releases. Given that Clinton effectively lost the Electoral College to Trump by just under 80,000 votes across three states (Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin), one can argue that Russia’s alleged hack and subsequent leak created a political environment in which enough voters were swayed away from Clinton to change the course of the election and American history along with it.

Then again, that’s just one analysis, and any claim that the DNC and Podesta leaks changed enough votes to swing the election toward Trump remains firmly in the realm of speculation. After all, what voter is going to say Russia played a role in convincing them to vote for Trump— especially when the leaks contained information that, presumably, legitimately turned them against Clinton?

Russia likely did not, according to available evidence, hack any voting machines. But the White House and U.S. intelligence appear convinced that Russia did, at the very least, attempt to socially engineer our collective perception of Clinton and her crew, thereby “hacking” the election.

Ultimately, “election hacking” is an imperfect, imprecise phrase. It appears to have misled some and infuriated others. It is also, if you want to get in the weeds about it, entirely correct.