One year into a double life sentence, Ross Ulbricht planted an apple seed in a sun-lit corner of his prison cell. It came to life in a damp towel before a guard took the sapling away. Instead of throwing it out, someone placed the small plant in the counselor’s office.

Just happy that the plant was alive, Ulbricht got another wet towel, dabbed it with vitamins, and started growing another tree inside his cell. His mother, Lyn Ulbricht, says that’s how her son makes his imprisonment “a little more humane.”

The mouse Ulbricht and his cellmate adopted—the prison has a lot of mice running around—isn’t so easily caught by authorities. Ulbricht feeds and houses it in a little cardboard box, but no guard has snatched the rodent yet.

Ulbricht turned 32 on Sunday, March 27. Apple seeds and pet mice are some of the tiny realities that occupy life for Ulbricht a year after being convicted of being the kingpin behind Silk Road, the multimillion dollar Dark Net drug market that launched him to international fame.

Ulbricht now lives in New York City’s Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC). His mother and father picked up from their Texas home to live in a small apartment nearby. It’s been a taxing trip for the couple—financially, physically, emotionally. Lyn is tired. She recently suffered a heart attack followed by a diagnosis of broken heart syndrome.

“It seems wrong that a citizen must be ruined financially to seek justice in the U.S., but this seems to be the case, at least for us.”

It’s been a year of near silence for Ulbricht, at least as far as the general public is concerned. He doesn’t speak to the media, so his mother has been his voice. Lyn travels the world speaking at libertarian festivals and raising thousands of dollars for her son’s appeal. She’s become a small political storm on a range of criminal justice issues like fair trials, due process rights, sentencing laws, and Internet privacy.

“It’s very clear that drugs are not the reason Ross is in there,” she told me at a meeting in Manhattan before visiting her son in prison. “He’s there because he was a political threat, because of the political philosophy of the site, of Bitcoin, of Tor, all of that.”

She’s not alone in that interpretation. Ulbricht’s trial and sentencing has been criticized in briefs to the court by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Drug Policy Alliance, Electronic Frontier Foundation, Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, Just Leadership USA, and former federal judge Nancy Gertner. Writing for Forbes, legal analyst Sarah Jeong called it “the trial that wasn’t.”

The U.S. government paints a very different picture of Ulbricht, whom a jury found guilty of seven felonies that include drug trafficking, operating a criminal enterprise, money laundering, computer crimes, and identity fraud. Prosecutors successfully argued that Silk Road vendors sold some 614,305 bitcoins—$80 million, at the time of the transactions—worth of marijuana, LSD, methamphetamines, and other illegal goods. The government also contended that drugs purchased on Silk Road contributed to the deadly overdoses of six individuals.

“Make no mistake: Ulbricht was a drug dealer and criminal profiteer who exploited people’s addictions and contributed to the deaths of at least six young people,” Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara said in a statement after Ulbricht’s sentencing. “Ulbricht went from hiding his cybercrime identity to becoming the face of cybercrime and as today’s sentence proves, no one is above the law.”

Then there’s the allegations of six murder-for-hire schemes. The government says there’s no evidence any murders ever took place, and they were never actually charged in court. In fact, neither the alleged murder-for-hire schemes nor Silk Road’s alleged role in the death of six young people were tried or proven in court. But both still played a major role in the sentencing.

Near the end of the trial, New York federal prosecutors urged the judge to “send a message” with a long prison sentence for Ulbricht because he was “willing to use violence to protect his enterprise.”

Of the seven felonies Ulbrich stands convicted of, nowhere on the list is murder for hire.

Ulbricht’s family and legal team are building toward an appeal this summer with significant costs. Compiling and binding copies of the brief alone cost $13,667.90 from PrintingHouse Press, a successful appellate services provider. Hiring a pathologist to go over two autopsy reports for people who allegedly died of drugs purchased on Silk Road cost $9,000. Overall, the family has raised more than $433,000 for the legal defense.

“It seems wrong that a citizen must be ruined financially to seek justice in the U.S., but this seems to be the case, at least for us,” she said. “I believe it is one explanation why 97 percent of the accused take a plea, even admitting to acts they haven’t committed.”

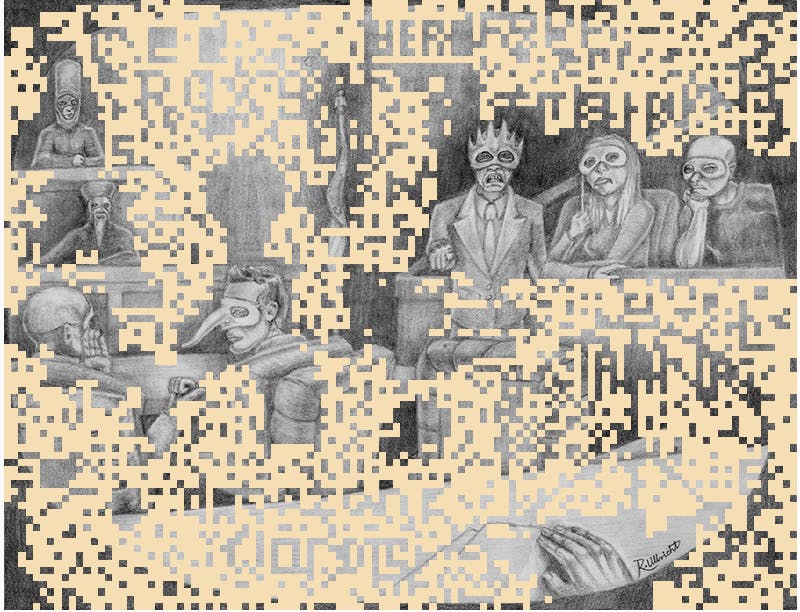

The Ulbrichts have been on an endless fundraiser since Ross’s arrest in October 2013. The latest fundraising idea came to Ulbricht in a dream, he said: An illustration of how he viewed his trial with judge, jury, and prosecutors dressed in horror garb. Supporters pay $1 per pixel to reveal the art and win prizes.

Sticking with Ross has been tricky on occasion, Lyn says, like when he’s moved from prison to prison with little or no notice to his family.

“What I’ve learned from the prisons, my saying is, why ask why? There’s no point, there’s no logic, there’s no explanation,” Lyn explained. “The only reason I knew he moved was a fiancee of another inmate—Ross and him had become friends, texted me and said, ‘Just in case you don’t know, Ross has been moved.’ I was about to go out on a train the next day with my sister up from Virginia to go see him. I didn’t know where he had been moved, where in the country he was. It’s a weird feeling to have no control.”

Without explanation, Ulbricht was moved from MCC prison in downtown Manhattan without any belongings, books, classes, or the friends he’d made over the last year in MCC. Once he said he finally began to settle in, it was back to MCC, still without any belongings. When he got back, Ross’s friends at MCC gave him his old books and chipped in for food.

“It was very sweet, very nice,” Lyn said. “Even though there’s pros and cons to the two places, as far as space and all that, I could tell he’s happier to be back with people he knew, people he’s friends with. He’s been living with a lot of them for a year.”

At MCC, Ulbricht resumed his role as teacher. When he first went behind bars, he quickly began a yoga class inside prison. Now he teaches a GED class to help prisoners get their high school degrees. Three students began correspondence college courses that they credit to Ulbricht, Lyn says. He’s taught physics as well, and continues to tutor individuals.

Ulbricht, who has a Master’s Degree in Materials Science and Engineering from Penn State, has taught physics to Davit Mirzoyan, who in 2012 pleaded guilty to orchestrating a $100 million Medicare fraud scheme, the largest ever charged.

“I didn’t know where he had been moved, where in the country he was. It’s a weird feeling to have no control.”

“It has been challenging to absorb the material, but Ross helps fill in the gaps and patiently explains the concepts to me,” Mirzoyan wrote in a letter to the court during Ulbricht’s trial. “He is attentive and enthusiastic and makes it fun to learn.”

Scott Stammers, who pleaded guilty last year to trying to smuggle 220 pounds of pure North Korean methamphetamines into the United States, became cellmates and fast friends with Ulbricht at the Metropolitan Correctional Center.

“I knew he was facing serious charges and going to trial, yet every night when he’d come back from court, I’d see him mingling with the other inmates, getting to know them, playing table tennis and just being at ease,” Stammers wrote. “Of all the people in our unit, Ross is facing the most time, but he never complains or tries to bring anyone down. On the contrary, he’s often the one to remind us to look on the bright side and be grateful for the blessings we still have.”

Teaching is both gratifying and distracting in a very narrow world.

“It’s very boring in there, it’s extremely limited physically,” his mother explained. “To be frank, Ross is very intelligent, and intellectually it’s hard for him to find peers to talk to. Not everyone—he’s met some people. But some of these people, he said, are very close to being retarded. They probably shouldn’t even be in there at all. He’s not snobby, he’s very accessible, makes friends with everyone. But I think he would love to have a great talk about artificial intelligence. That’s not gonna happen. He gets bored.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated for context and clarity.

Illustration by Jason Reed