If you’re familiar with Peter Daou, it is probably from the Democratic primary posting wars of 2016, which then morphed into the #Resistance movement that has dominated American political Twitter since Donald Trump was elected president.

Along with Tom Watson, Daou was the preeminent “Hillary Man,” the nickname given to guys who stood against the perceived “Bernie Bro” menace online, tweeting in defense of Hillary at every opportunity in the run-up to 2016. He was such committed Clintonite that he launched the liberal media watchdog site Verrit which aimed to largely to combat “fake news” about HRC and those in her orbit.

Daou has spent countless hours on social media defending Hillary Clinton and posting against the enemies of liberalism. Though he has recently committed the cardinal #Resistance sin of offering an olive branch to Bernie Sanders, if his book is any indication, he doesn’t regret his time spent in the posting trenches.

In fact, he wants you to join the fight.

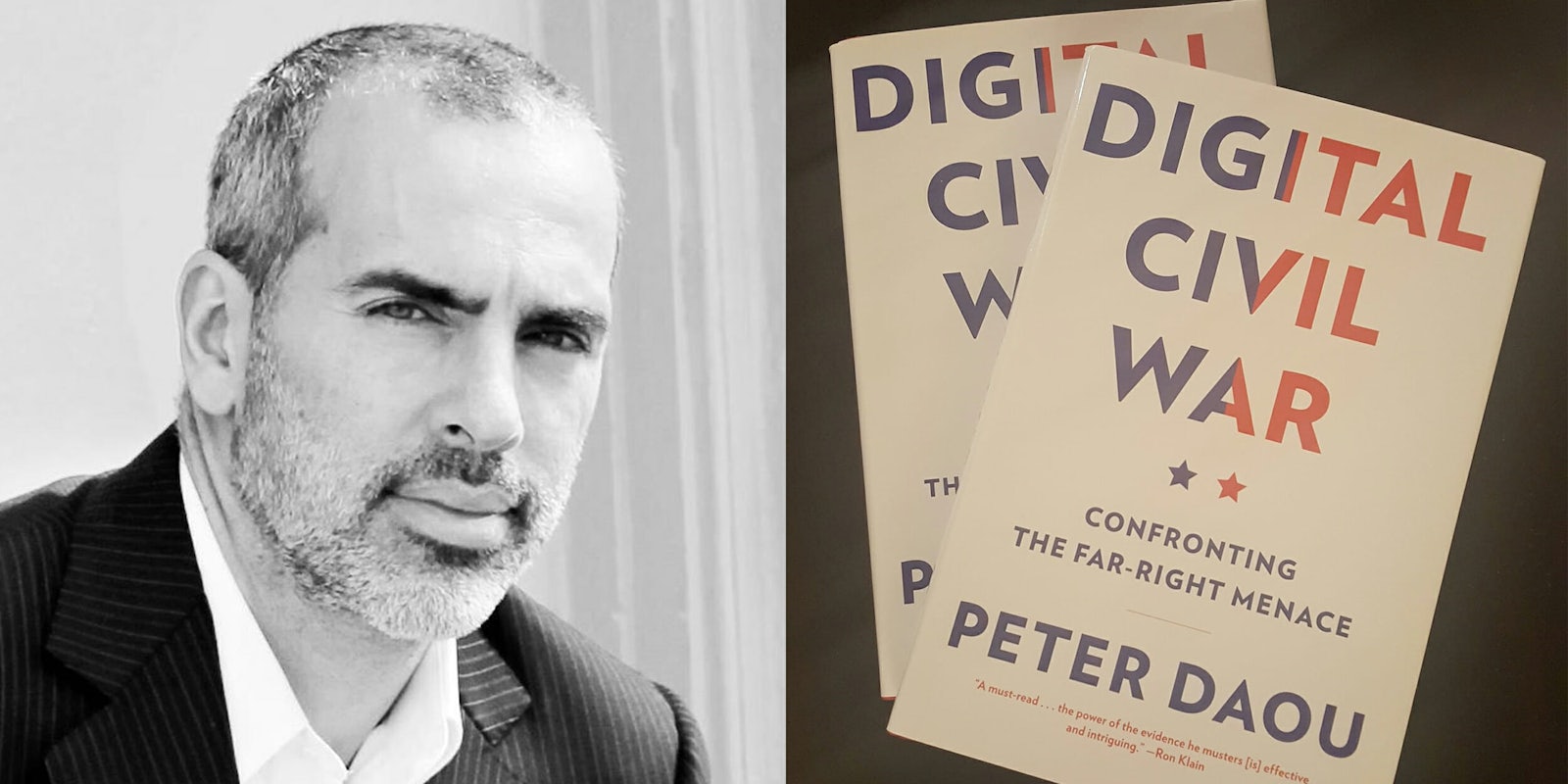

In his new book, Digital Civil War: Confronting the Far Right Menace, Peter Daou lays out the case that the new frontier in the battle between liberals and conservatives is social media and it is every liberal’s patriotic duty to post.

Daou believes the stakes are high and the situation is grave. He writes without a hint of irony, “Logging on every day is entering a war zone, a gauntlet of verbal abuse, gaslighting, and harassment. The unrelenting toxicity of social media is a feature, not a bug, of digital warfare.” He even goes as far as to say, “The Lebanese Civil War…prepared me for America’s Civil War” (Daou came of age in war-torn Lebanon).

Perhaps, Daou’s views are extreme, but even if he speaks hyperbolically, Digital Civil War does work decently as a piece of political media criticism. Daou effectively discusses issues that make online discourse unbearable. He takes aim at the “both-siderism” of mainstream media, access journalism, the siloed-off media world of Fox News viewers, and the rise of fake news.

In a kind of digital oral history, Daou chronicles various hot button issues and the social media movements that have accompanied them. He reminds us of #TakeAKnee and #ShoutYourAbortion. He is careful to note that Parkland student Emma Gonzalez amassed more Twitter followers than the NRA. With heavy sourcing and statistics, and direct quotes from Twitter accounts both massive and obscure, Daou creates a kind of Twitter oral history of the big moments in the #Resistance, from the Robert Mueller investigation to Charlottesville.

The irony of Daou’s work, however, is that he falls into the same trap he is criticizing in the online right. He repeatedly scolds conservatives, and particularly figures in the #MAGA ecosystem, for unleashing vitriol online that muddies the discourse and poisons the nation’s politics. While it is clear that Daou has good intentions, his assessment of the political landscape is just as limited as his opponents’. He hates the trolls, but just like them, he measures political success by rhetorical wins, not material change.

In his conclusion, he argues, “These bitter social media clashes are now a full-blown Digital Civil War, a relentless barrage of personal attacks, threats, harassment, and hate, where rational discourse and reasoned debate are the first casualties.”

He goes on to say, “When we clash over our ideals and principles, it shouldn’t be a contest of who can be the meanest and snarkiest, who can humiliate and “dunk on” each other, who can join the biggest and angriest mob … Good people want to make things better for those around them. It’s part of life’s purpose.”

But how do we make things better? Daou believes it is rational discourse aimed at “finding common-sense solutions.” For Daou, politics is the discourse, and winning that discourse will fix politics.

It doesn’t take a Marxist scholar to point out that Daou’s reduction of our political realities to social media infighting minimizes the material conditions that actually comprise politics. He sees Republicans as a falsely aggrieved group, rather than people with legitimate concerns.

Daou writes, “…no cultural myth is more pervasive, no dogma more entrenched, than that of the small-town white male being the quintessential or ‘real’ American, and his struggles the only meaningful ones.” While that may be true, it doesn’t mean that voters on the other side don’t have meaningful material concerns. The opioid crisis persists, manufacturing is leaving America, and Hillary Clinton didn’t campaign in Wisconsin. And all of that happened off of Twitter.

For Daou, material conditions are relevant to politics, but they are secondary to messaging. The very first line of the book reads, “Politics is the competing stories we tell our country, our history, our government, our community, and ourselves.” As a left-wing critic, I would argue that politics is power and who gets to wield it. Daou is talking about spin.

What happens online can impact people’s material conditions, but no matter how many followers Emma Gonzalez has on Twitter, her classmates are still dead.

Like his opponents on the right, Daou and his comrades in digital arms have divorced their discourse from reality. Daou writes about Twitter posts as if they are actual blows against Trump, and about “prominent members of the Resistance” as though they are effective activists.

Daou references a rogues’ gallery of resistance liberals in Digital Civil War, relying almost exclusively on their version of events to diagnose our political moment. Twitter personalities he quotes include but are not limited to Amy Siskind, “Propane Jane,” Eric Boehlert, Imani Gandy, Oliver Willis, Andy Richter, Jill Filipovic, Sarah Kendzior, Leah McElrath, Malcolm Nance, John Fugelsang, Jessica Valenti, Charles P. Pierce, Philippe Reines, Bess Kalb, Marcus Johnson, Symone Sanders, Matthew Chapman, Ed Kilgore, Melissa McEwan, and Joy Reid.

It is important to list all of these names because it is difficult to find an ounce of political disagreement between any of these twenty people. They retweet each other (and Daou) constantly, and choosing to populate the book with this many quotes from such a specific corner of political Twitter demonstrates the ideology of the text.

The effect of chronicling the internet rhetoric of this narrow, ideologically similar group is that an outsized emphasis is placed on the issues they champion. If you only listen to these pundits’ Twitter feeds, you would believe the American political problem is one of civility, decorum, and patriotism. You would also believe that America’s political problems can be solved by getting rid of Trump and besting his supporters online. You would also believe that Russia single-handedly swayed the presidential election and that Hillary Clinton’s campaign is not to blame for her loss.

Digital Civil War makes reference to other viewpoints from time to time but it is incidental in the all-consuming battle, err, war, between the #Resistance and #MAGA.

If you had the Twitter experience that Daou has had on a daily basis for the last four years, you would believe in the digital civil war as well. The last line of your book on politics might be the same as Daou’s. You too might write, “For blue Americans in the twenty-first century—and for principled partrios across the ideological spectrum—the Digital Civil War is about preventing that descent into tyranny by confronting the far-right menace [on Twitter] before it is too late.”

This narrow view of American politics ultimately undercuts would could have been a fine piece of media criticism from Daou. When he breathlessly writes lines like “Lt. Gen. Mark Hertling and information warfare expert Molly McKew likened Russia’s election intrusion to Pearl Harbor and the terrorist attacks of 9/11,” it is painfully clear just how divorced the #resistance Twitter is from material politics.

It may be an obvious point, but it is worth repeating: no one has actually died in this Digital Civil War.

Too often, Daou mistakes empty rhetorical gestures for meaningful action. For example, he praises Beto O’Rourke’s defense of Colin Kaepernick in a video that went viral last year. He fails to mention the O’Rourke voted for a “Blue Lives Matter” bill and has a mixed at best record on race.

Chapters on abortion and guns are probably the most effective in Digital Civil War because Daou is able to tie rhetorical digital activism (or “hashtag activism”) to real world activism. Daou argues that pro-choice commentators pushing back against pro-life hardliners when it comes to issues of female bodily autonomy is useful. Similarly, he argues that discourse around guns and the second amendment is important for a safer society. Daou rightly points out, “The massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, is seen as a turning point in the gun-reform right. Parkland survivors have used social media to mobilize, organize, and inspire people across the country.”

But sometimes tweeting doesn’t work and Daou is loathe to admit that. In chapter 5, “Battle for Faith: Un-Christian Values,” Daou argues that Trump is not worthy of the adoration and respect of the Christian right. He then outlines some of the best social media owns various people have lobed at Trump to that effect. Despite their efforts, evangelicals still overwhelmingly support Trump. It’s unlikely that anyone who wasn’t swayed by the Access Hollywood tape is going to be swayed by Melissa McEwan calling Mike Pence a “snake.”

https://twitter.com/Shakestweetz/status/930436713981337600

Beneath the self-righteousness and myopia Daou sometimes indulges in, Digital Civil War offers some interesting ideas. If he had written this book as a post-mortem on the last few years of internet combat, offering the same number of Twitter sources and back-and-forth analysis of various hashtag wars and trending topics, Daou might have ended up with a useful document of a peculiar political moment.

It is in the book’s call to action, the idea, taken for granted and accepted for face value, that the online battle between #Resistance and #MAGA is a meaningful fight for the soul of a nation, where Daou goes wrong. Digital Civil War makes the reasonable argument that in some ways, Twitter is real life. Misinformation and fake news have real world consequences. Hashtags, informational threads, and tweet blast calls to action can be effective organizing tools.

But, there is more on Heaven and Earth than what is contained in your timeline.