Opinion

It has become a trend in late-night comedy to apologize for enabling President Donald Trump.

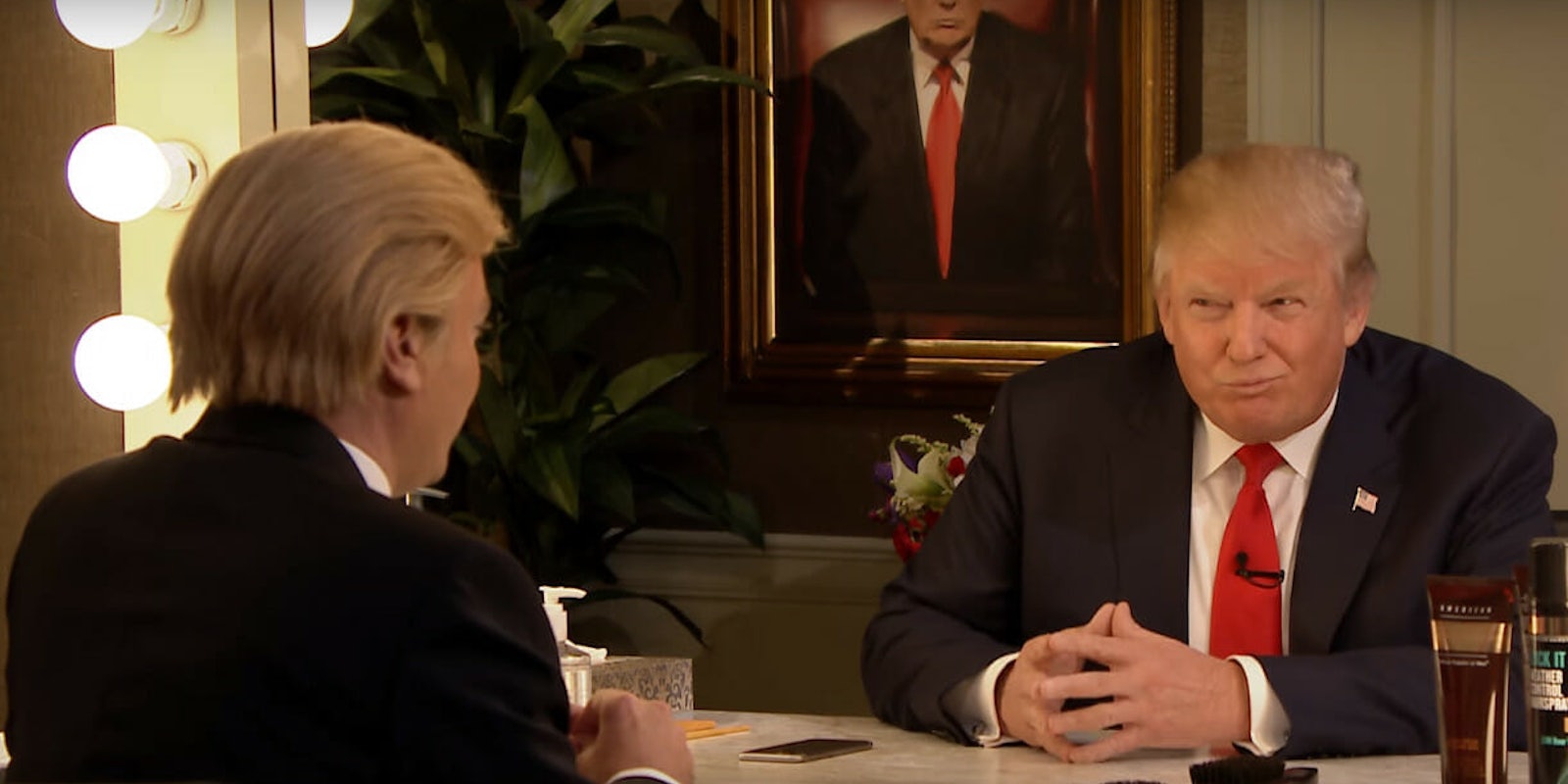

The latest mea culpa came from Jimmy Fallon, who apologized last week for his infamous hair-tousling interview of the commander-in-chief back when he was a general election candidate in September 2016. He told the Hollywood Reporter, “I’m sorry. I don’t want to make anyone angry—I never do and I never will. It’s all in the fun of the show. I made a mistake. I’m sorry if I made anyone mad. And, looking back, I would do it differently.”

Fallon isn’t the first late-night star to apologize for hosting Trump. Several Saturday Night Live cast members have expressed regret for allowing Trump to star on the show almost exactly one year before the 2016 general election. Shorty after Trump was elected, Kate McKinnon came onstage dressed as Hillary and played Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” in an attempt to make up for the show’s collective enabling of Trump. The gesture was meant as one of defiance, but to many observers, it came off as far too little, too late.

While some reflection about the media’s collective normalizing of Trump is certainly in order, this particular problem has been with us far longer than the Donald’s political career. Politicians shouldn’t go on late-night shows at all. Politicians have been using comedy to normalize their views and rehabilitate their image for decades. It’s time we stopped letting them.

Imagine this. Two months before a presidential election, a candidate who would go on to win the country’s highest office, only to become mired in scandal and divide the nation, cracks the audience up as a guest of one of America’s most-watched comedy shows. Of course, I’m talking about the time Richard Nixon appeared on Laugh-In and said “Sock it to me?” in 1968.

One key difference with Laugh-In is that the writers were under no delusions that they were being subversive or challenging the status quo. Head writer Paul W. Keyes was such a diehard Nixon supporter that he had even written jokes for his speeches. Keyes wanted Nixon to take a little bit of the sour note off of his image, which many on the right blamed for his 1960 loss to John F. Kennedy.

Since its origins, SNL has allowed politicians of both parties on its air. In 1976, President Gerald Ford made a cameo after Chevy Chase popularized a caricature of the president as clumsy and aloof. Presidential hopefuls have appeared on the show regularly ever since: Jesse Jackson, Al Gore, Sarah Palin, Rudy Giuliani, Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, John McCain, and many other politicians have made appearances.

Why do politicians agree to go on a show that is ostensibly built to mock them? Just like Nixon, other politicians know the appearance will humanize them. Ford only agreed to go on SNL because of the popularity of Chase’s sympathetic impression. It is delusional to think that every politician since hasn’t made the same calculation.

It is ludicrous to think that you can have a politician on your show and satire them effectively. Being backstage or in the writers’ room means you are literally in on the joke. Just look back at Tina Fey’s incredibly sympathetic Sarah Palin impression which culminated with a cameo by the former Alaska governor. You have to wonder if the hockey mom harbinger of the Tea Party would have faded from our collective consciousness long ago if it wasn’t for Fey’s impression. SNL clearly seems to think Fey and Palin’s legacies are connected: The show had Fey reprise her role as the would-be vice president this year.

You might argue that more traditional late-night shows, as opposed to sketch shows, have a long history of political guests. This is true. Johnny Carson helped rehabilitate Nixon for a national audience as well. But, Carson didn’t consider himself a political comedian, and if anything he sought to defend the status quo. Carson having political guests is a great argument for why today’s more politically minded hosts shouldn’t. Carson knew something that today’s comedians don’t: Politicians can be your friends or your targets. They can’t be both.

This problem has become more pronounced in recent years, as the line between journalism and comedy has blurred. While Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert were always careful to insist they weren’t in the journalism business, the shows that have followed in their footsteps have had an explicitly journalistic feel. Many of them have journalists on staff.

Meanwhile, late-night hosts like Seth Meyers and Jimmy Kimmel have taken on a more earnest and thoughtful pose under Trump. It seems that every network late-night host is more concerned trying to be the next Walter Cronkite than joke writing. The desire for reasoned voices in the age of Trump and the legacy of Stewart—who always carefully made sure to dress and talk like a newsman, but never be a newsman—has led to this blurring between journalism and comedy.

By hiring journalists and looking like journalists, these satirists fall into the trap of needing to “represent both sides” and “maintain objectivity” like actual journalists. This isn’t the goal of satire. You don’t hear from the Archbishop of Canterbury in The Life of Brian. Jonathan Swift didn’t reserve column space for the British prime minister in A Modest Proposal. Hitler doesn’t make a winking cameo at the end of The Great Dictator.

Satire and journalism are very different things.

As American comedy has adopted this more earnest, journalistic tone, the idea that comedy should be attacking politicians has faded further from view. Kimmel recently played a friendly game of basketball with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Trevor Noah’s debate with Tomi Lahren was lauded as respectful by all the “serious pundits.” (I would characterize the interview as “flirtatious,” and neither is a good look.)

It is clear that having a politician on a late-night comedy show for a cameo doesn’t make the bit funnier. It doesn’t make the satire sharper. Generally, it benefits the politician while offering the show nothing beyond a potential ratings boost. (The ratings of Trump’s SNL episode were the highest in years, good for them.)

At best, a politician’s appearance on a late-night show will be viewed as harmless. At worst, as was the case with Trump’s SNL appearance, it can cause the audience to lose faith in a show’s comedic abilities. It can make you look like a sellout, cozying up like a house cat.

It doesn’t even help the writers. Comedy writer and Struggle Session podcast co-host Jack Allison would know. Allison is a veteran of a major network late-night show, and as someone who has seen behind the curtain, he feels much the same way.

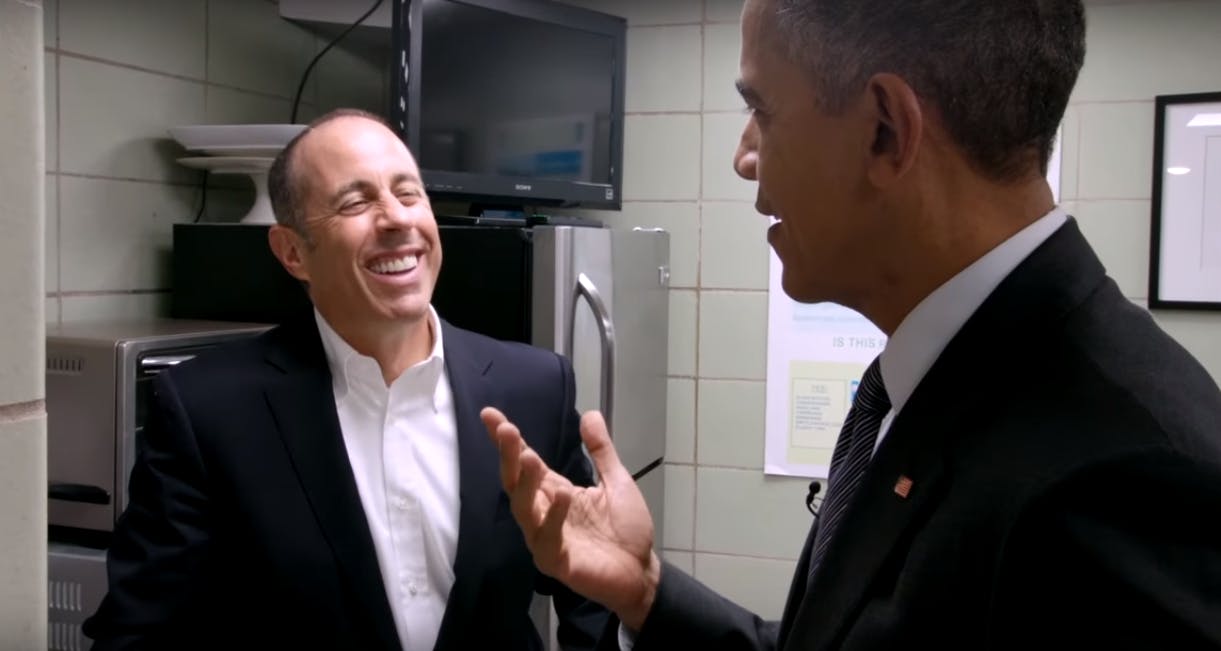

“I say no more politicians on late night shows, or any non-news television, really. Our art and entertainment is at its best when it speaks truth to power, and it’s pretty hard to do that when you’re walking on eggshells because you hope to get a viral video with the people who hold that power. When politicians go on comedy shows especially, they’re getting the free benefit of a highly paid staff of people working together to make them seem not only funny but more human. We should be using our platforms to hold these peoples’ feet to the fire, not for building them up and helping them look cute. I don’t care if it’s Obama getting coffee in cars with comedians, Joe Biden visiting Leslie Knopf, or Trump hosting an entire episode of SNL to promote his presidential run—keep these people off TV, and don’t force your writing staff to write their propaganda,” Allison told the Daily Dot.

If Allison understands this and the writers of Laugh-In understood this in 1968, it’s obvious that today’s late-night hosts are either willfully ignorant or blinded by their pursuit of ratings.

There is no comedic value to having a politician on a late-night show. There is, however, huge potential to damage the show’s credibility. The only positive that could come out of having a politician on as a guest is that the host and their staff could gain more access and goodwill from these elected officials, and be commended for their commitment to civil discourse.

Access, goodwill, and civility are no recipe for good satire.