President Obama recently unveiled a dramatic plan aimed at making your Internet connection suck less.

In one of a slew of new initiatives launched in anticipation of Tuesday’s State of the Union address, Obama announced a dramatic push to improve broadband Internet service for people around the country. The president argued that millions of Americans are underserved by their current options for high-speed Internet. One way to rectify that is to allow local governments to build their own municipal broadband networks.

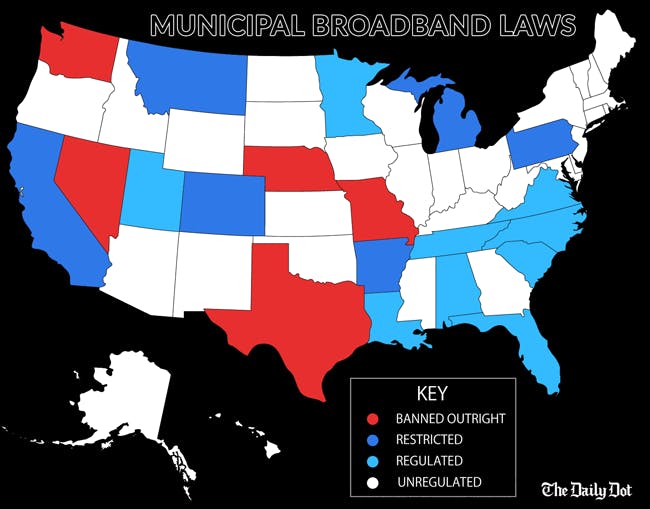

Problem is, state legislatures around the country have passed laws making it considerably more difficult for these public Internet projects to get off the ground. In some states, building municipal broadband is prohibited altogether. President Obama has instructed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to do what it can to invalidate these laws and allow local government to easily set up their own municipal Internet networks

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler is broadly supportive of the idea, although Republicans on the commission have come out in opposition. Wheeler proposed something very similar himself while speaking at cable industry event last year.

Even so, it’s not as if the targeted laws could all be made to disappear in an instant. It’s likely to be a slow process for a range of reasons: The rules were largely put in place at the behest of powerful private telecom firms leery of facing additional competition; invalidating those laws sets the stage for a pitched states’-rights battle; and the laws themselves are far from uniform, meaning there’s likely no single way to push them aside.

In addition, the regulatory authority under which the FCC will be attempting to invalidate the laws, Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act, is extremely broad. It says that the FCC “shall encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans” by “[promoting] competition” and “[removing] barriers to infrastructure investment.”

Figuring out how each of the state laws fit into the puzzle will likely be tricky—especially in the face of stiff Republican and cable-industry opposition.

A handful of states, like Texas and Nebraska, have outright bans on governmental agencies creating their own ISPs and then selling Internet access to the public. However, most of the rules in place are considerably more complicated.

Some states, like California and Montana, have said that local governments can only embark on broadband projects if there are no private entities in the region willing to provide service. On one hand, this rule stops deep-pocketed government entities from undercutting a private sector unable to keep up; however, one of the main goals of brining in municipal Internet is sparking just this type of direct competition.

A report by the New America Foundation noted America’s Internet infrastructure lags behind many other developed nations because major incumbent cable Internet providers rarely face direct competition in a given geographic area. In other words, most Americans have only one, sometimes two, Internet providers available in their area.

For example, when the country’s two largest Internet service providers, Comcast and Time Warner Cable, announced their intention to merge, the companies pointed out that they don’t directly compete against each other in any location in the United States. Therefore, they largely get to act like monopolies. Comcast has developed the reputation of being the worst company in America, but its status as the only option for many consumers leaves people with few, if any, alternatives.

A recent report the Government Accountability Office found that municipal broadband networks typically offer faster speeds for lower prices than private networks. As a result, the private networks then have an incentive to make the necessary investments for providing better service. However, when states like California restrict municipal broadband projects to areas where there isn’t already service, the entire competition-promoting aspect gets wiped out.

Other states have rules in place that require municipal broadband projects to add in additional costs into their models, even though those costs don’t actually exist. For instance, even though local governments can borrow money at much lower rates than private firms by issuing bonds, they may still have to act like they’re paying higher rates and therefore would be required to charge high prices to their customers.

“In North Carolina,” municipal broadband advocate Chris Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance tells the Daily Dot, “the law says that muni networks would have to calculate the taxes that a private company would have to pay—which is an interesting turn of phrase as Time Warner Cable and others often pay much less than they ‘would have to pay’ due to fuzzy math.”

“The impact of these laws is that a community that moves forward opens itself up to years of litigation as courts will have to figure out what such poorly conceived laws mean,” Mitchell added. “So the danger isn’t so much the cost of additional dollars but the exposure to years of court room wrangling.”

Here is a map showing all the states with anti-municipal broadband laws Obama wants the FCC to go after, along with brief descriptions of the restrictions in place in each state.

Alabama: Municipal broadband services can’t use local taxes to pay start-up costs, eliminating one of the biggest advantages possessed by government infrastructure projects. Each stand-alone service has to be self-sustaining—meaning no “triple play” bundles of phone, TV, and Internet service. A public vote is required before every project.

Arkansas: Only municipalities already providing public electricity service can offer broadband.

California: Utilities can only provide municipal broadband to an area if no private entity is willing to do it. If a private firm pops up, the municipality has to immediately sell or lease the system it spent years building—likely at a loss.

Colorado: A public vote is required in all areas other than where a community has specifically requested service from private companies and been refused.

Florida: All projects are required to be profitable within four years, which rarely happens for any broadband network—even in the private sector. A special ad valorem tax, unique among infrastructure projects, is imposed on pubic broadband efforts.

Louisiana: Requires a public referendum before each municipal broadband projects. Public providers are required to shoulder higher costs than a private company would be required to pay in a similar situation.

Michigan: Before kicking off a public Internet projects, municipalities must seek offers from private firms and cannot build themselves if they receive three or more qualified bids.

Minnesota: A public vote with 65 percent supermajority is required before starting any municipal broadband project.

Missouri: Municipalities are prohibited from offering telecommunications services to the public. Stand-alone broadband is currently exempted, but a bill working its way through the state legislature would eliminate that exemption.

Montana: Governments can only provide broadband if there is no private company offering service in a particular city. If a non-governmental provider starts offering service, municipality can shut down within months.

Nebraska: Public entities are banned from offering broadband service to the public.

Nevada: Towns larger than 25,000 and counties larger than 55,000 are banned from offering any form of telecommunications service.

North Carolina: Public providers are forced to deal with numerous legal roadblocks not encountered by private firms, such as tacking additional costs onto their rates to simulate what a private company would have to pay. All municipal broadband projects must pass public vote before launching.

Pennsylvania: Municipalities are barred from providing comparable services offered by private company. (“Comparable” can only refer to data speed.) Governments are not allowed to look at other factors like price or quality of service.

South Carolina: Municipal networks have to add phantom costs that a private provider might have to pay.

Tennessee: Electric utilities can bring broadband to their service areas, but cannot expand beyond it. For example, Chattanooga’s municipal fiber network is one of the best in the country and this rule prevents it from expanding service to neighboring cities.

Texas: Public sector agencies are prohibited from offering Internet service to the public, both directly and through partnerships with private firms.

Utah: Accounting regulations placed on municipal broadband networks mean that the state has a “de facto prohibition” on such services.

Virginia: Municipal providers are not allowed to subsidize service or charge rates lower than private firms. Nor are they allowed to offer “triple play” packages because providing cable television service is banned.

Washington: Public utilities cannot provide telecommunications service directly to customers—although they can offer wholesale data service to private providers, which can re-sell it to customers.

Photo by Steve Jurvetson/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | pfly/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed