After the FBI shuttered a burgeoning online narcotics bazaar called the Silk Road in 2013, an anonymous bureau spokesperson proudly gloated about the feds’ ability to net some of the dark web’s biggest players.

“This is supposed to be some invisible black market bazaar. We made it visible,” they told Forbes at the time, adding, rather menacingly, that “no one is beyond the reach of the FBI. We will find you.”

Three years later, and it seems as if the dark web’s consortium of online drug peddlers—many of them Silk Road copycats—interpreted the FBI’s threat as more of a challenge. Not only have authorities the world over done a lackluster job of cracking down on internet drug dealers, the shady sector has experienced substantial growth under their watch.

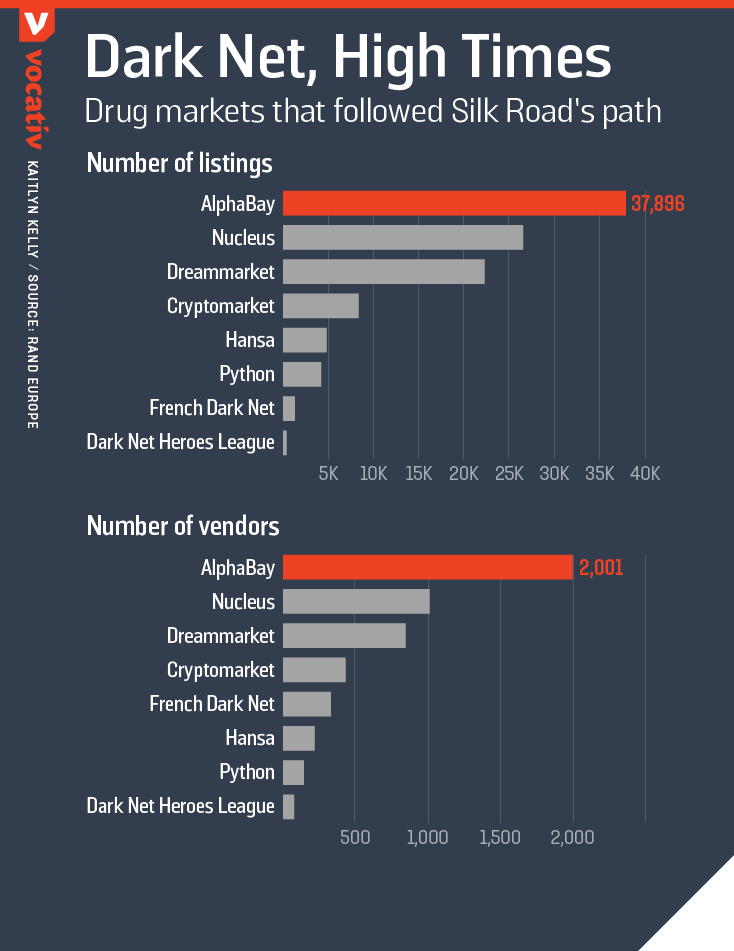

According to a new report from RAND Europe, online drug transactions on dark net markets (DNMs) have tripled in the three years since the Silk Road was taken down by the FBI, while revenues have roughly doubled in the same time period. Analyzing data from January, the report found that “around 50 so-called cryptomarkets and vendor shops where vendors and buyers find each other anonymously to trade illegal drugs, new psychoactive substances, prescription drugs, and other goods and services,” have effectively taken the Silk Road’s place.

Commissioned by the Netherlands’ Ministry of Security and Justice, the study scraped eight of the largest 50 “live cryptomarkets and single-vendor shops.” Researchers discovered that these eight contained 105,811 listings—roughly 80 percent of all listings across all 50 DNMs. Of those listings, about 57 percent were drugs. The eight DNMs analyzed were found to generate a total monthly revenue of $14.2 million; a month before it was shut down by the FBI, researchers believed the Silk Road raked in more than $7 million. “So, despite law enforcement intervention and various exit scams on these marketplaces, cryptomarkets have survived,” the report says.

Tim Bingham, a drug trends researcher who has followed and written about the Silk Road for years, said such findings don’t surprise him or his professional peers at all. “I think a number of us expected, once Silk Road went down, that other markets would spring up,” he told Vocativ in an interview. “You see the expanse of vendors having their own market places. That was its own natural progression—it was bound to happen.”

The RAND report notes the ever-shifting nature of internet drug businesses. Bingham believes that while Silk Road was hugely influential both in pioneering many aspects of the dark net drug trade as well as creating a trustworthy and anonymous community, that model is not the future. Rather, a more decentralized approach to vending appears be in the cards. “I think you’re going to start seeing server-less market places where it’s very much peer-to-peer, where you can download an open source code,” he said. “I think that’s going to be a development.”

Regardless of what form they take, sellers have been able to proliferate simply because of widespread demand for these types of marketplaces. Consumers flock online, the report says, because of the transparency and comprehensiveness DNMs provide, and because they think doing so is easier and safer than purchasing drugs offline.

For John Collins, coordinator of the London School of Economics’ IDEAS International Drug Policy Project, DNMs don’t exclusively highlight the possible futures or business-side of drugs—they may point a way forward for policymakers, as well.

“The dark web may indeed reduce the harms of drugs and drug markets through the elimination of violence as a mechanism for contract enforcement and giving buyers more control over quality,” Collins told Vocativ in an email. “Some, as the RAND report highlights, are concerned this may lead to new consumer initiation. I think in the current climate where the harms of prohibition and the war on drugs are so visible in so many contexts, that anything which offers short term harm reduction for illicit markets should be explored.”