Ten years ago, the autonomous car was science fiction. Now, its adoption is inevitable.

Jeff Klei, president of Continental AG’s North American region, predicts that 54 million autonomous vehicles (AVs) will be on the road by 2035, and Boston Consulting Group estimates 12 million fully autonomous units will be sold annually by that time.

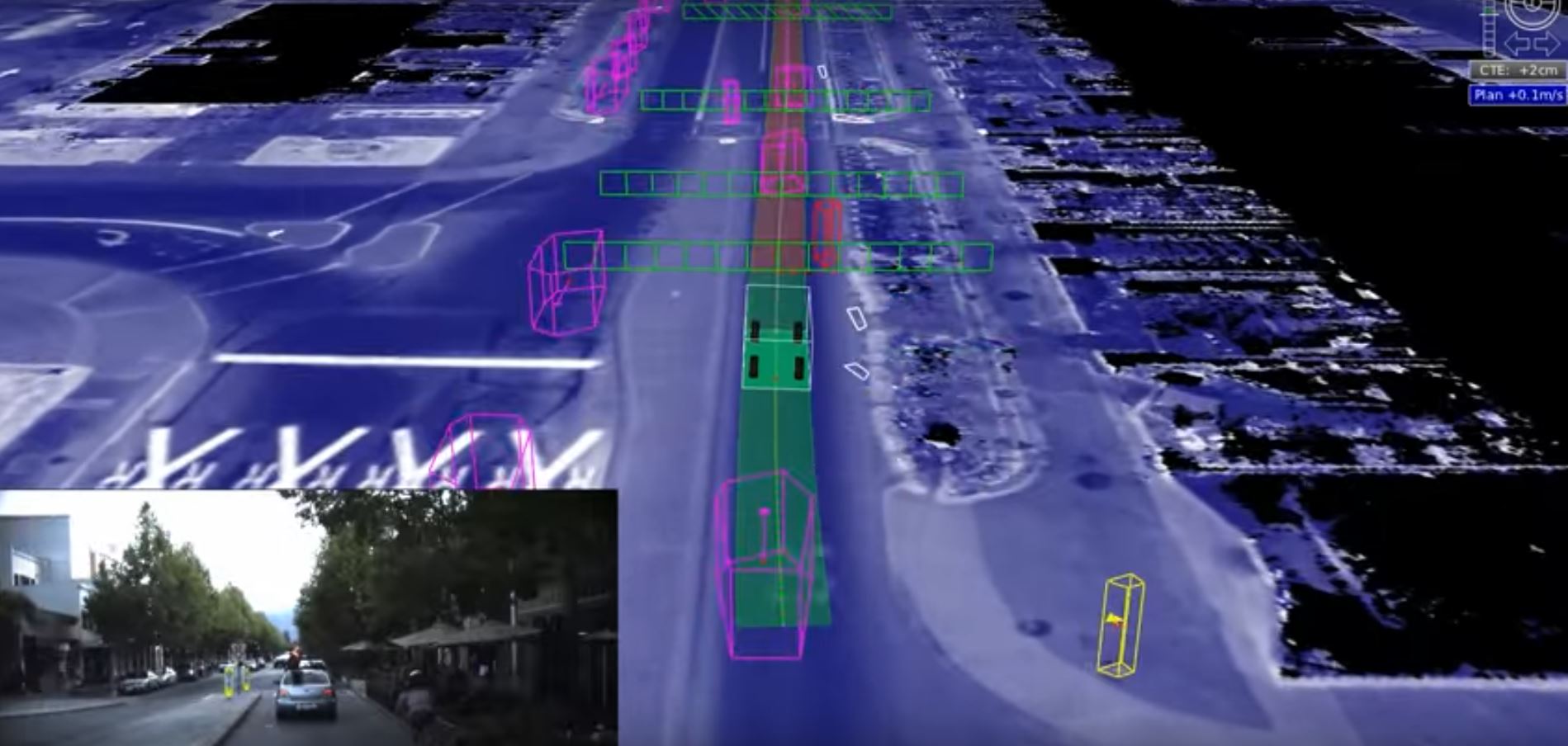

But the technologies used for enabling self-driving cars—light detection and ranging (Lidar), radar, cameras, and sensors—have limitations that are exacerbated by a problem in America that has existed for more than 40 years: its aging transportation infrastructure. America’s roads aren’t compatible with self-driving cars, and automakers aren’t happy.

The CEO of Volvo North America, Lex Kerssemakers, “lost his cool” when one of his cars failed its test during a press event at the Los Angeles Auto Show, according to Reuters.

“It can’t find the lane markings!” Kerssemakers said to Mayor Eric Garcetti. “You need to paint the bloody roads here!”

Poor lane markings may seem trivial, but it’s a big enough problem for Tesla CEO Elon Musk to weigh in, calling the issue “crazy,” after the Tesla Autopilot feature failed to recognize which lane the car was driving in.

“If the lane fades, all hell breaks loose,” Christoph Mertz, a research scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, told Reuters. “But cars have to handle these weird circumstances and have three different ways of doing things in case one fails.”

Traffic signals are also causing issues. Because the majority are not connected to a network, cars must rely on their cameras and sensors to determine if it’s OK to drive through an intersection. This becomes a problem when traffic signals are exposed to direct sunlight. A similar limitation led to the first autonomous car death last year. In July, a man died in his Tesla Model S because the on-board cameras were unable to detect the side of a white truck in bright sunlight. The Tesla drove under the trailer and got its roof sheared off.

America’s infrastructure is failing

For all of the high marks America receives for technological innovation, it lags when it comes to infrastructure.

“The way we pay for and build infrastructure has been frozen in place for decades, and the vehicles using the infrastructure have advanced dramatically,” said Tim Sylvester, CEO of Integrated Roadways, at SXSW.

The nation’s infrastructure received an overall grade of “D-” in a report card published this week by the American Society of Civil Engineers. That grade took 16 categories into account with roads, dams, and airports receiving a “D” rating, while mass transit came in with a “D-.”

An estimated 65 percent of U.S. roads are in poor condition, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, with the country’s transportation infrastructure system rated 12th in the World Economic Forum’s 2014-2015 global competitiveness report. “Inadequate supply of infrastructure” is also seen as one of the country’s problem factors for doing business.

Poor markings and uneven signage on 3 million miles of paved roads in the United States are forcing automakers to develop more sophisticated and expensive sensors and maps to compensate.

The auto industry strikes back

AVs are covering millions of miles of roadways across the country, and they will need to cover millions more before becoming available for commercial use. Automakers aren’t waiting for federal or state governments to improve infrastructure before putting their vehicles on the road.

Mercedes says its “drive pilot” system in the 2017 E Class will work on roads without lane markings by using 23 sensors that look at guard rails, barriers, and other cars to keep in their lanes at up to 84 miles per hour.

The company made it clear at SXSW that it believes extensive 3D mapping is required for fully autonomous vehicles to become a viable product in spite of the current state of roadways in the U.S. Mercedes is working with rivals Audi and BMW to turn Nokia’s former Here into a mapping application for future self-driving cars.

“It can look beyond limitations of on-board cameras and radars, even around corners,” said Deiter Zetsche, CEO of Daimler AG and head of Mercedes-Benz. “A map with real-time data knows about the icy parts of the road around the next curve, or an accident up ahead. It helps you find the last parking spot downtown. If you want fully self-driving and safe cars, you need super accurate and reliable, continuously updating maps.”

Other auto manufacturers are continuing to advance current technologies so they can overcome the struggles they discover when testing automated vehicles under certain conditions.

“The first approach that most are taking is self-sufficiency with a vehicle with some measure of redundancy and a lot of robustness built into the vehicle,” said Peter Kosak, the global director of urban mobility at General Motors. “The idea is to use a combo of sensors—Lidar, radar, cameras, and a lot of AI created from simulations and real world testing, to reach self-sufficiency and not rely on infrastructure.”

But another, potentially more reliable way of ensuring the safety of an autonomous vehicle, is enabling a car not only to see infrastructure, but also to converse with it.

Cars must talk to the roads

In vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication, a car uses a network connection to speak with the infrastructure around it. The infrastructure gathers global or local information on traffic and road conditions and suggests certain behaviors on a group of vehicles. For example, the speed and acceleration of vehicles and distances would be suggested by the infrastructure on the basis of traffic conditions to optimize overall emissions and fuel consumption, according to the IEEE Control Systems Society.

“You can’t just rely on vehicle sensors,” Klei told Auto News Europe at Automotive News World Congress. “You need data from the cloud to tell you what’s going on.”

Audi became the first car company to use V2I communication in August. The new feature lets the company’s cars communicate with traffic light infrastructure in select cities across the U.S. The car receives signal information from the traffic management system that monitors traffic lights with its built-in LTE connection.

“This feature represents Audi’s first step in vehicle-to-infrastructure integration,” Pom Malhotra, general manager of connected vehicles, said in a statement. “In the future we could envision this technology integrated into vehicle navigation, start/stop functionality, and can even be used to help improve traffic flow in municipalities. These improvements could lead to better overall efficiency and shorter commuting times.”

It could even reduce pollution on the roads as the industry moves toward electric vehicles. If vehicles knew how traffic lights operated in real time, carbon production would go down about 200 billion tons per year, according to Matt Ginsberg, CEO of Connected Signals.

There is no question V2I could provide significant benefits for AVs, but funding for those projects remains a wild card. The average cost of a single V2I site could reach $51,650, which would cover planning, equipment, installation, connectivity, and signal upgrades, according to the General Accountability Office.

Who’s paying for it?

Trillions of dollars need to be invested in today’s roads for federal or local governments to responsibly address congestion and compatibility with self-driving vehicles. There are two ways the government gets money from its roads: a fuel (or road use) tax, and toll roads. Neither method is consumer friendly, nor has either proven very effective. But self-driving cars present unique avenues of revenue from parties outside the public sector.

“The funding model that exists for infrastructure in the U.S. hasn’t changed in decades,” Hector Negroni, CEO at Fundamental Credit Opportunities, said at SXSW. “It’s benign and unsophisticated compared to our needs. The primary means of funding needs to be augmented by the participation of private capital, and it’s an important part of evolution in the marketplace when you think of the participants.”

Those participants include some of the largest technology and automotive companies in the world. On one side of the spectrum are Google, Facebook, and Uber, new players to automotive who have been rigorously testing AVs for years. Then, of course, there are the traditional automakers, all of which are racing to release the first viable fully autonomous car. Users, the government, and the tech industries need to be ones to fund the roads. It will require a public-private partnership, and a community of legislators and researchers and engineers and technology companies and automobile manufacturers, according to Andrew NG and Yuanqing Lin at Baidu.

“There is a shortage of funding for the scope and scale of needs that we have,” Negroni said. “It’s unlikely the immediate answer is going to be to open the floodgate of federal dollars downstream. We have to make it more competitive for private capital and rethink our models (gas and property tax) for revenue.”

The shift from public to private funding could be spurred by the ace the government holds in its back pocket: big data. The value of data to private companies cannot be stressed enough. Tech and automotive companies need to know how people operate—their wants and needs—in order to be competitive in the marketplace. As technology demands 5G wireless, the amount of data the government collects is going to be an incredible source of value for advancing infrastructure.

If federal and state governments can work with automakers and technology companies to find a solution to funding infrastructure, it could usher in a new era for safer, more efficient travel, and may even lead to the end of human driving altogether.