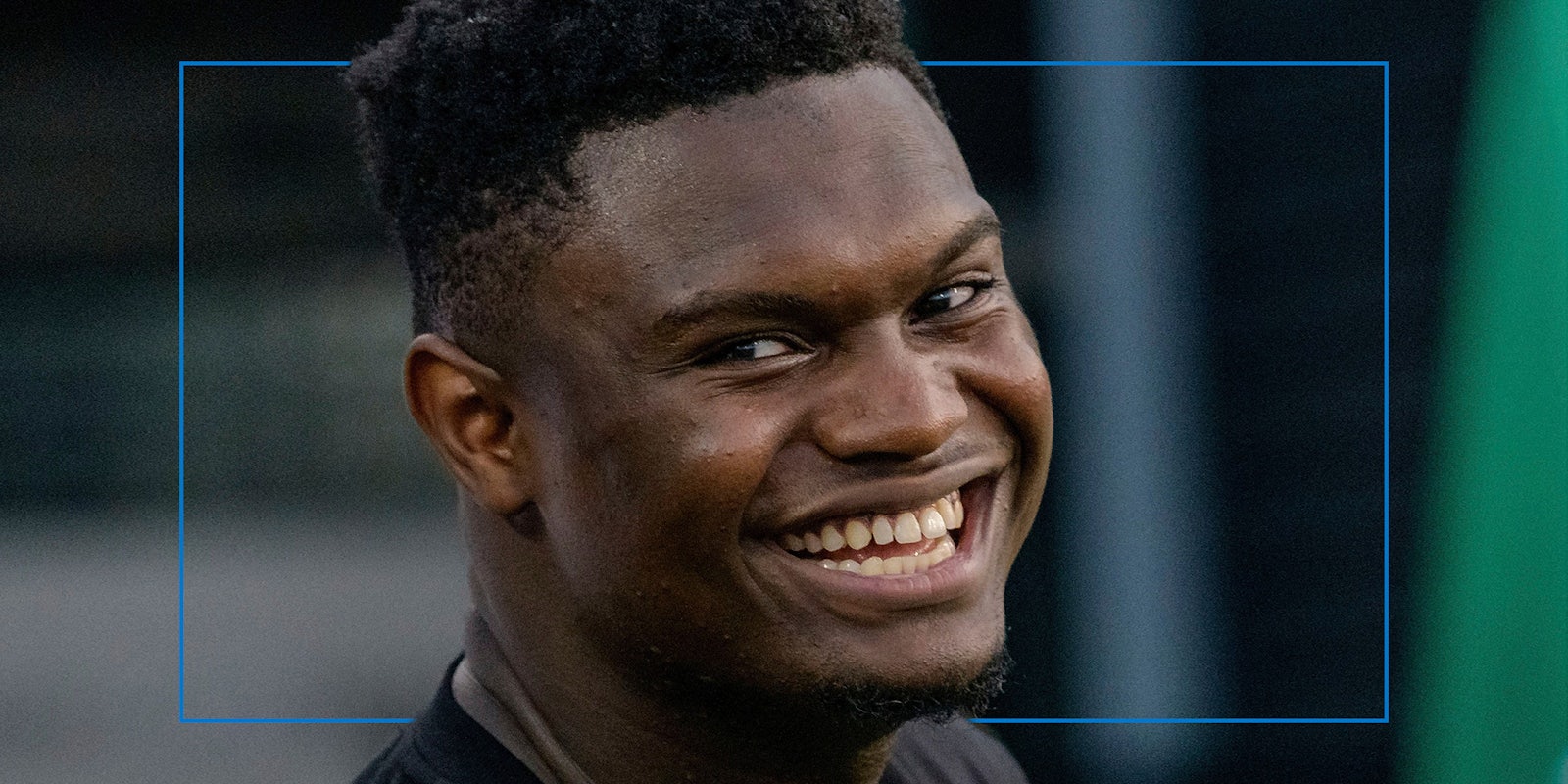

If you only found out who Zion Williamson was through Twitter, the memes would provide the impression that he’s some oversized athlete, mainlining all the food he could find. Never mind the fact that the New Orleans Pelicans forward is one of the NBA’s great young talents, averaging 25.7 points and seven rebounds so far in his career. Never mind that he’s been beset with injuries, which has paused or curtailed the employment of much smaller, slender athletes. No, Zion Williamson, once a teenage darling of the NBA Twitter, has been reduced to a fat guy.

Combined with the consistently shorthanded online discussion around athletes, in which brevity rules, most context has become ironically lost in a time where more information is available than ever before. We demanded access to information that we’ve now collectively refused to utilize.

“It’s become a language for how we understand different athletes and how we classify athletes,” said Dave Zirin, author of The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World, and commentator at the sports and politics nexus. “But it’s existed before, more broadly outside the sports world, for really as long as there been an internet. The idea of targeting, insulting, and flattening people down to one dimension is a lot to overcome. Once you’re an athlete caught up in a meme, it takes work to overcome that.”

The name-calling and meme generation in NBA social media has become both cottage industry and a growing, dimension-erasing monster that affects, flattens, and compounds the public opinion of stars. Players’ perception within social media—somehow simultaneously ephemeral and lasting—is now almost as important as their real-life on-court play. It has also become emblematic of a much larger set of issues. How has it come to this?

A brief history

Author of Best Damn Hip Hop Writing: The Book of Dart, historian and researcher Dart Adams believes the issue dates back to the advent of the 24-hour news cycle leading to social media emergence. Access and information about sports almost instantly came with a cable box and later a modem.

“Back in the days, like the ’70s, ’80s, and even like into the ’90s, when we finally got mass media covering sports and the widespread marketing of it, there were the beginnings of what we have now, like NBA Entertainment putting out the VHS tapes, Inside Stuff on Saturday morning, ESPN, ESPN 2, all that happening,” said the Boston native. “The video games are coming into existence, with Lakers Versus Celtics, then NBA Live from EA Sports.”

“It started around 2001-2002 when people got 24/7 internet, with DSL, T1 lines, and then cable modems. We had whole generations and micro-generations whose interactions with sports have come through the vein of the internet and seeing it through the lens of the internet, and talking about it on the internet.”

What Adams notes, along with the chronology, is significant. Sports video games were a time of early, critical, and siloed chat rooms. A period of message board experiences where people could espouse their opinions and beliefs, often problematic, into the ether. The period also sparked distinct online cultures, many unsettling to various degrees and often under cover of anonymous characters and avatars. The ordinary person with a modem could realize and wield a sense of strength that they could not live in real life.

“[The era birthed] trolling culture, and that’s meme culture before we knew it, as we know it now,” recalled Adams. “I’d say meme culture started around the era of MySpace going into YouTube. I’d say between 2005 and 2007 because I was one of the dudes who used to read Vice.”

Vice, during this era, was an intriguing (and often problematic) touchpoint given, as Adams recalled, that “They made fun of everything.” Adams added that, for better or worse, these notions and behaviors would eventually make their way online. These micro-generations of fans and their language would invade Twitter, essentially treating the platform similar to the message boards of their youth, scaling down nearly everything—and stripping context.

“They have discourse about sports or real-time events in that same vein,” continued Adams. “There’s no nuance. There’s no layering. There’s no, ‘Let’s consider the full context.’ The important thing is to get the jokes off, get them off rapid-fire, get the ‘LMAOs.’ Anybody saying, ‘Actually, the full context is,’ and ‘What you’re forgetting is,’ are entirely thrown to the wayside because you’re taking the fun out of what they’re there for.”

The flattening

For Zion Williamson and many other current athletes, meme culture and analysis-in-280-characters has warped serious discussions around them where the sentiment of the memes/jokes/player-shaming outlasts even the ephemeral quality of social media. Take fellow NBA star Russell Westbrook: A half-season with the LeBron James-led L.A. Lakers today threatens to tank the complete tale of the tape of his spectacular career, which leads to another fascinating quandary that’s grown with the stripping of context: A lack of ever-disintegrating awe and scale.

Social media and meme culture’s flattening of public figures on the whole has reduced their humanity to mere entertainment. But these aren’t pop stars created by a record label, lucky to have a good-enough voice and the right look. Russell Westbrook and Zion Williamson are much better at their craft than most commentators—armchair or employed by a sports network—are at their jobs. Who else can verifiably say they are among the roughly 50 most remarkable people—in the world—at their job?

And who can make the memes? Who gets to apply the undue pressure via jokes and stereotyping? Who is allowed to have power over whom? The idea that Zion Williamson looks like Family Matters character Carl Winslow or former WWE superstar Mark Henry is untrue, weird, and also racist, depending on who suggests it.

The very idea goes back to the notion that Black athletes are part of their white-assigned apparatus as America’s entertainment vehicle, as unreal persons valuable only for unserious consumption. It can become part of a particularly nefarious end of digital blackface that regularly goes unchecked in sports culture, along with bashing players with unusual intensity or negative humor.

For Phillip Lamarr Cunningham, media studies professor at Wake Forest University, another question is: Who benefits in driving the online culture?

“Most of these conversations about players’ abilities are often in reaction to some of the guys who have [TV] shows,” said Cunningham. “I think if you look at Twitter enough, it’s usually responsive to mainstream commentators.”

Cunningham believes there’s a more significant issue in how networks could be perceived as compromised to an extent, increasingly slave to increasingly bite-sized content. No matter how much information is packed within, the inherently descaled, micronized content is often lost in the sea of memes and unserious tweets.

“If you’re just a journalist—you’re just covering the story, and you’re providing analysis on player movements or whatever the case may be—that’s one thing. But when you have to provide some hype or sensationalize to draw eyes, you have to say wild, inflammatory stuff to drive conversations, get clicks, and get visits to your site, it becomes different.”

No end in sight?

Sports media’s growing relationship to meme culture and the need to capture increasingly shortened attention spans are not unique but represent a unique totem. The descaling and refusal of context have bled into all forms of formerly weighty press. The lack of seriousness and depth is dangerous and fraught with profound real-life and existential hazards. It is flattening out much more than naturally massive basketball stars. Is there any way to cease its progress? Is there a public appetite for context? Will Zion Williamson stop being the fat guy?

Zirin notes a reported uptick in print book sales and audio and ebooks. There is hope and hunger for complete stories and context. But Cunningham isn’t sold. Owing to social media’s addictive nature, he recalls numerous passages and studies about social media’s effect on memory. “Short of us—as a society—naturalizing long-form reading again, I don’t know if we can get back to some sense of, ‘Hey, I have this curiosity, and maybe these 280 characters get me to investigate more.’ I think that I think the cat’s out the bag.”