“It feels like casting a spell and releasing it out into the world.”

Interdisciplinary artist Yumi Sakugawa is explaining what it’s like to share her content on Instagram where, if an image touches the right collective nerve, it can circulate widely and touch more people than she ever imagined.

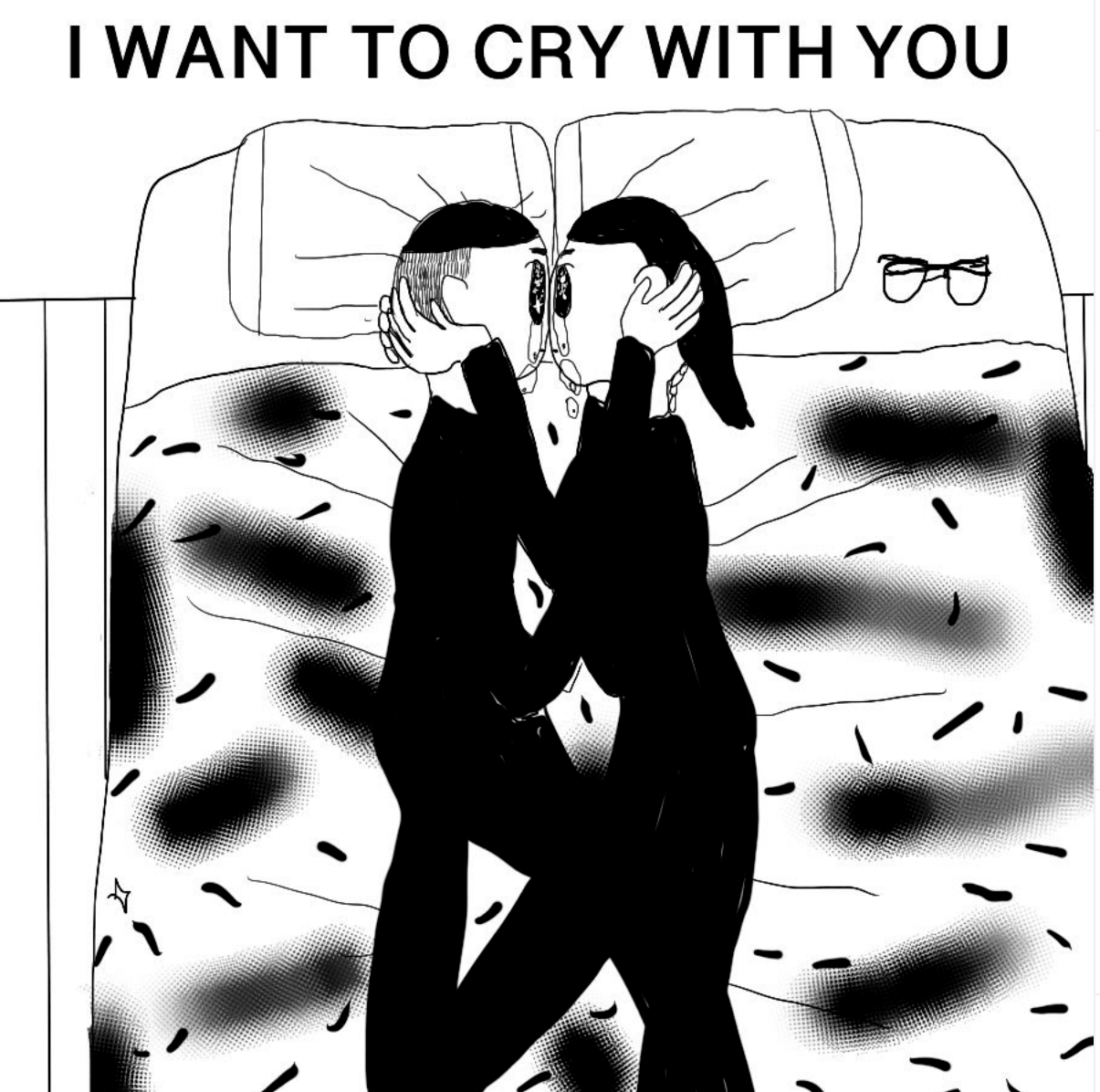

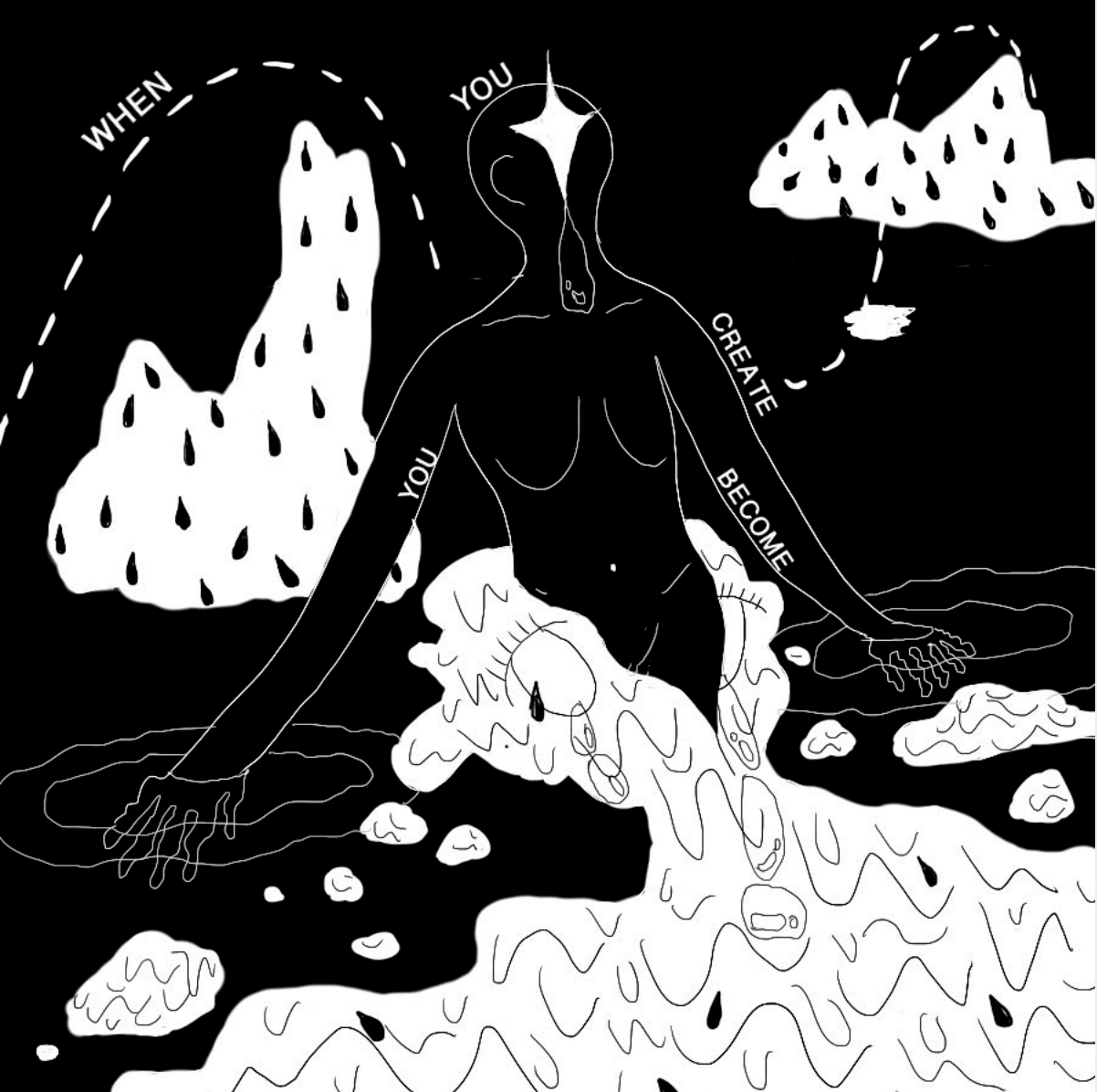

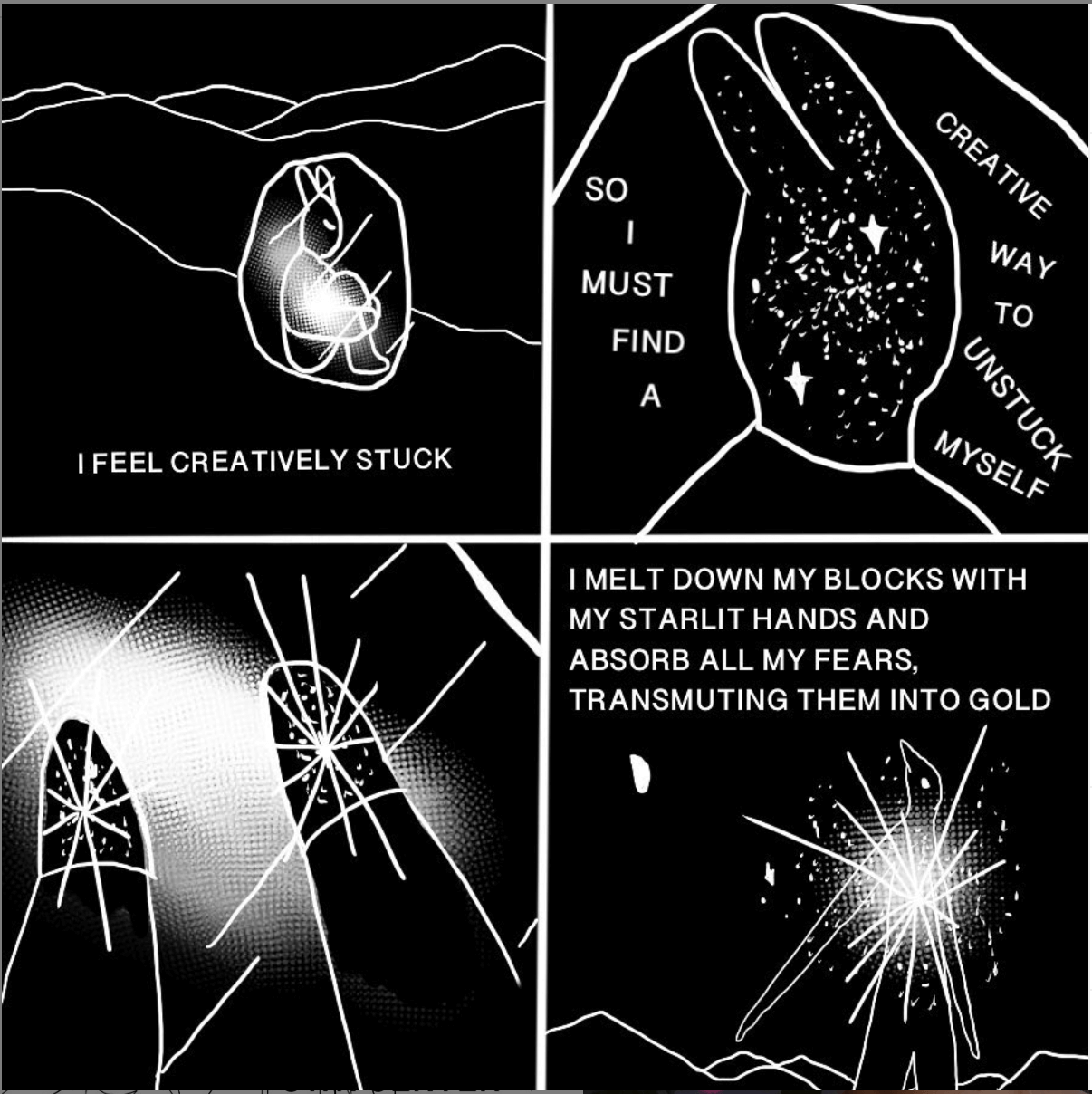

Since September, she’s kept a daily practice of posting at least one drawing and one text-based image to her account. Sakugawa, 34, studied fine arts at the University of California, Los Angeles. She creates art about pleasure, desire, sadness, and the monstrous shame that gets in the way of our creativity. Her Instagram is part diary, part self-help manual, and it subverts what we’ve come to expect from what is typically an attention-seeking, carefully curated space. Sakugawa shares raw ideas and deep, dark pain. But her messages are bold and empowering. She takes ownership of fear and shame and encourages her followers to do the same.

“For me that feels like such a great privilege and honor to do that for people,” Sakugawa tells the Daily Dot.

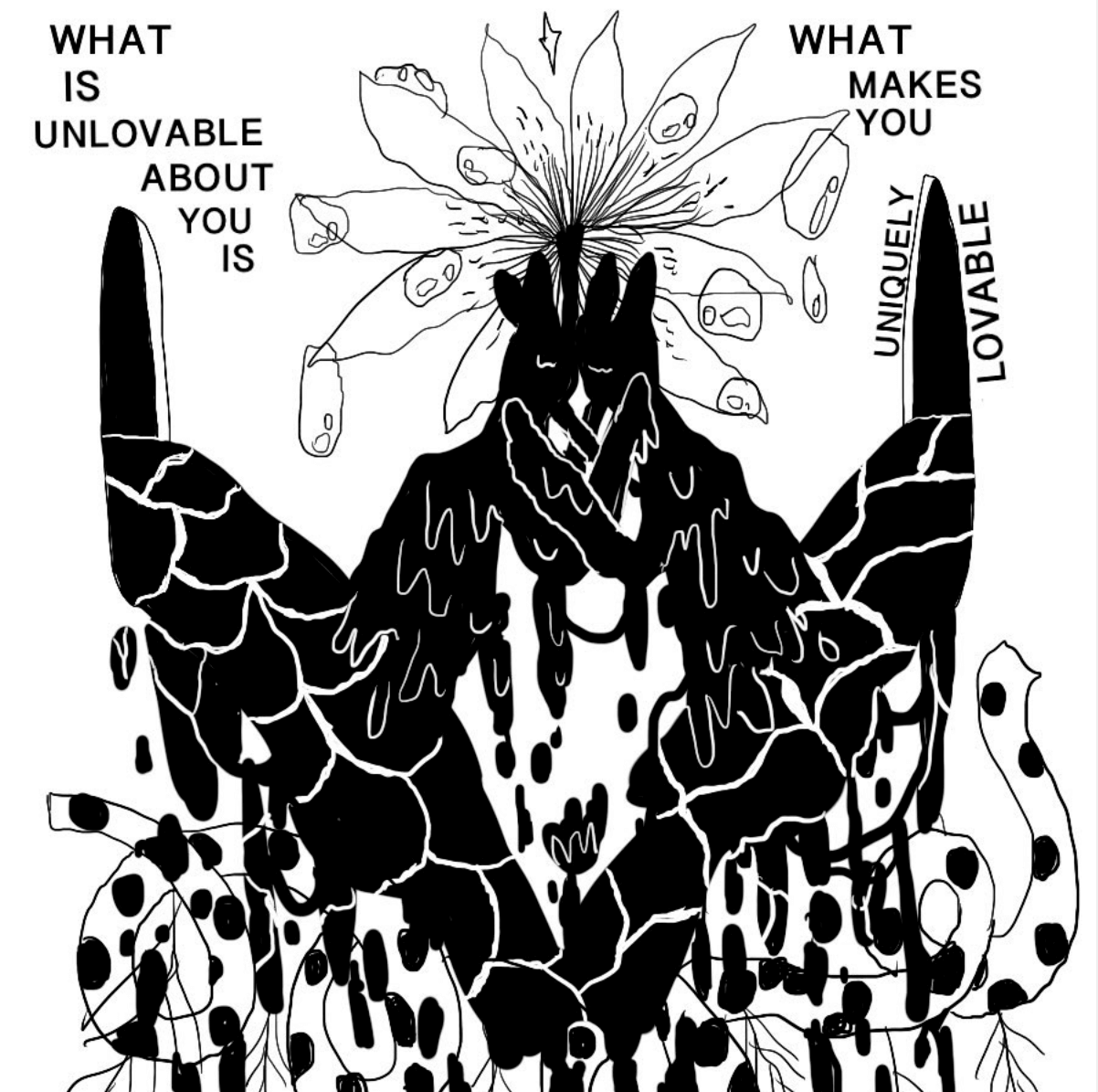

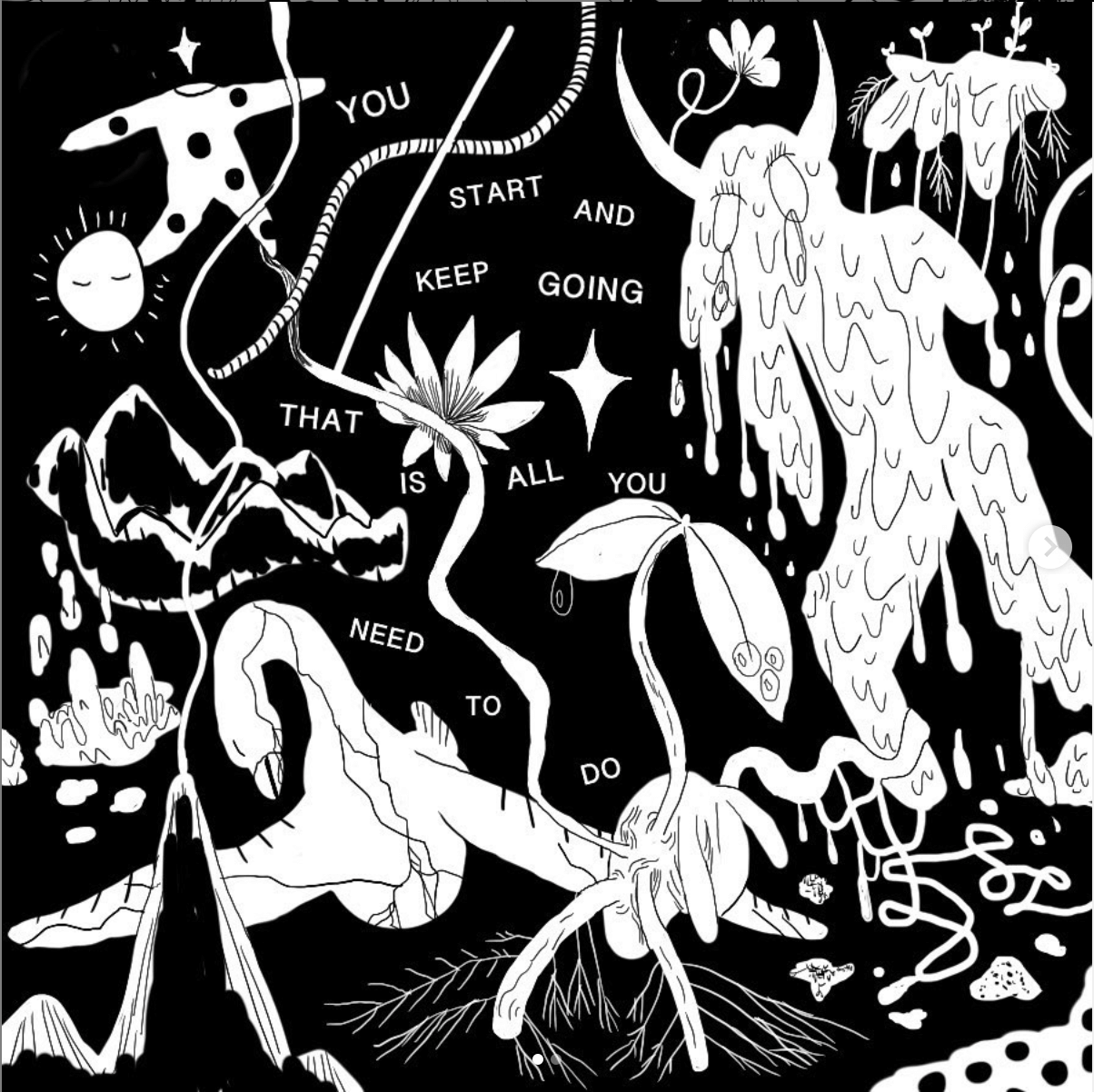

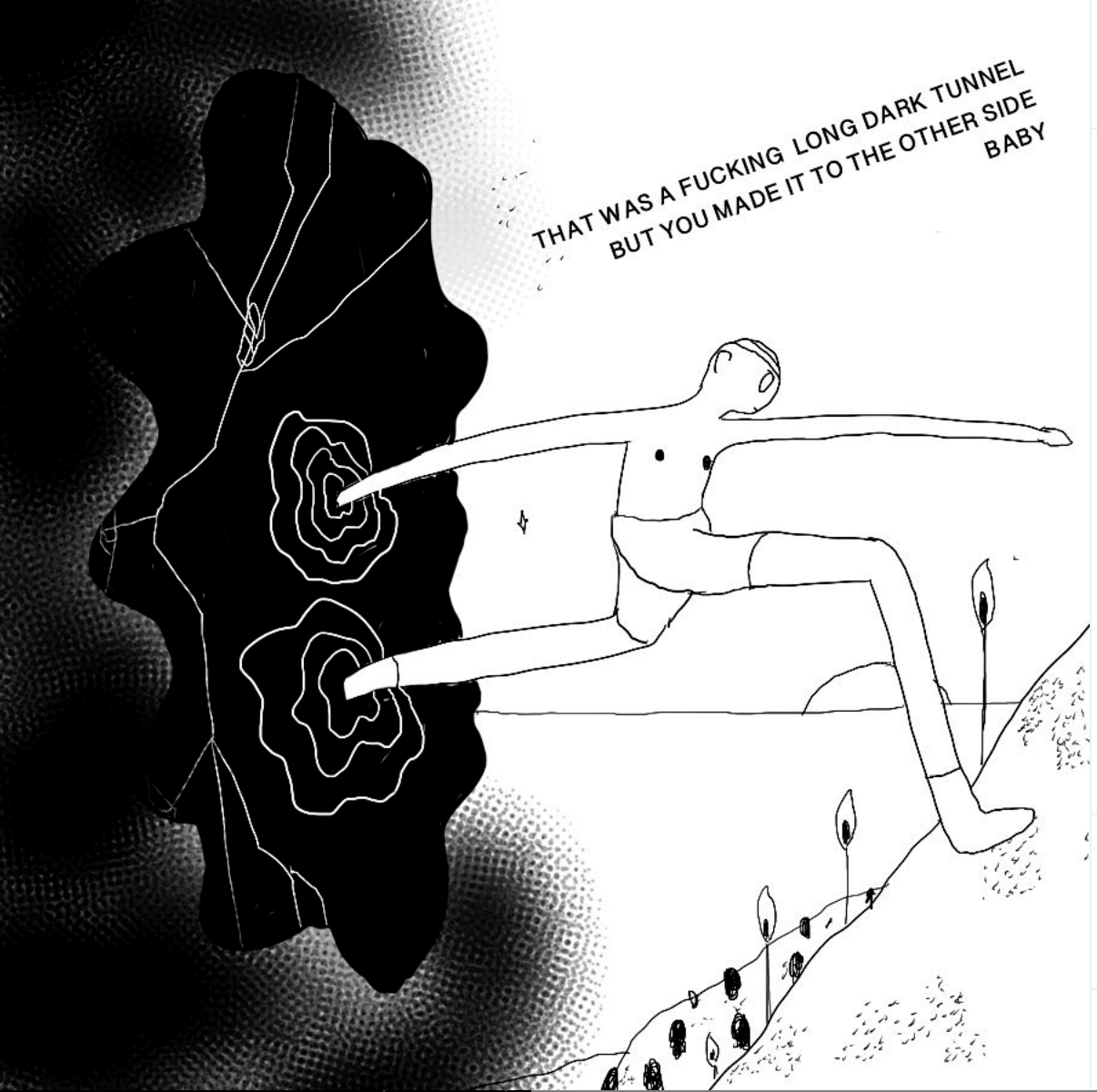

Sakugawa isn’t afraid to get dark, and it shows. Her Instagram feed is now home to black and white renderings of demons, tears, and unmet desires. Sharp precise lines give way to figures that expand, meld and open up to reveal shimmering jewels of hope. Discoveries of self-love are paired with revelatory affirmations. But this is far from watered-down “love yourself” rhetoric. In an era when flowery self-help memes have become increasingly pervasive, Sakugawa’s art offers a welcome jolt. Like a cup of black coffee served piping hot, her art is as comforting as it is electrifying.

Earlier in 2019, Sakugawa, who defines herself as an interdisciplinary artist, began experimenting with what she shares on social media. She decided to share dating experiences on her Instagram stories in a series she called “mindful dating.” According to Sakugawa, the ephemeral nature of Instagram stories allowed her to take risks she normally wouldn’t. She tells the Daily Dot, “It was really fun to play around in this space that was really very public but was hidden in plain sight… I was able to play around with how open and vulnerable and honest I could be with my feelings.”

READ MORE:

- Tara Booth’s Instagram art embraces the comedy in mental health struggles

- Artist says Thinx underwear campaign ripped off their memes (updated)

- The delicate balance of disclosing mental illness on social media

- 10 essential self-care tips in the wake of #MeToo

Prior to posting about her dating experiences, Sakugawa had reached a point where she felt she needed to take a social media sabbatical. “It just wasn’t fun for me. It just touched on so many insecurities I had about a fear of being judged, FOMO, being hyper-aware of group dynamics and social hierarchies,” she says. “It brought up so much social anxiety in me that I had to take a break from it.”

But Sakugawa says she learned a lot from her time away from social media, which has allowed her to share in new ways. “That was this period of healing for my mental health [and] also really reflecting on how I relate to people in general. Because of this long hiatus, I really did a deep excavation around ideas of power and visibility, and using your voice to speak on things that are scary but honest.”

Emboldened by the positive feedback she got from her mindful dating stories, Sakugawa revisited her Instagram feed with a renewed sense of mindfulness and began challenging herself to post drawings and text-based images on a daily basis.

While she often draws inspiration from her personal experiences, Sakugawa notes that she’s also mindful of what her audience might connect with. “I’m always interested in finding that sweet spot in between [what’s] resonant with what I’m going through… and then to share that with people who may be going through so many things,” she said.

“It’s really grounding for me too, to have this daily practice,” she added.

The content Sakugawa has been sharing since she began her daily practice bristles with raw creative energy. Her art never feels superficial or polished. Instead, by excavating deeper levels of discomfort, Sakugawa reveals ways in which the very shame that makes us feels small can become a tool for expansion and empowerment. In the world of her drawings, which often appear to be set against the backdrop of outer space or some other dimension, the figures stretch and shift as they transmute their pain to experience new levels of freedom and empowerment.

“I think for me social media is a space where I push the edges of my comfort zone,” Sakugawa says. For example, while she typically enjoys the restriction of a black and white palette, Sakugawa has recently posted drawings where she experiments with color.

Sakugawa also hosts online “creativity workshops” where she prompts attendees to investigate their creative blocks and reshape them into inspiration. Blending journaling and drawing prompts with meditation, Sakugawa creates a space where participants can safely explore the beliefs that might be holding them back. A workshop I attended in October was surprisingly playful, considering the content. Participants described their creative shame monsters with humor and bemusement. When we created the opposite of our shame monsters, participants cheered each other on, delighting in our diverse, newly birthed creations.

Recently, Sakugawa has also begun co-hosting workshops for Asian femme-identifying people to help them overcome the “shame of not being enough.” Sakugawa, who has authored “self-help” books in the past, says that self-help spaces tend to be overwhelmingly white. She cocreated IRL workshops in the hopes of offering other Asian femmes a support space for the specific challenges they face that might otherwise go unspoken. “I think there’s an unacknowledged psychic trauma in having to assimilate—in not feeling that you belong in the culture of your family and in the culture [within which] you’re pressured to assimilate,” Sakugawa explains.

Whether she’s hosting IRL workshops, digital seminars, or posting to her Instagram feed, Sakugawa seems to be stretching herself to hold space for collective transformation. Given her humanitarian aims, her choice to engage so heavily with the internet, a space that’s often seen as highly negative, could seem counterintuitive. But Sakugawa sees it differently: “I think of the magical cosmology that we’re all part of one web… I think the internet is an interesting place to think about the interconnected web that we’re all a part of. We’re all linked.”