Nothing good happens on the internet after 2 a.m. That’s what I told myself after I clicked into my filtered inbox (aka the abyss) on OkCupid late one night and received a message explaining “all the things” one user and his “boy” would do to me in a dark room should they get me alone. There it was, sitting heavy in by my inbox, in graphic and grammatically traumatic detail.

As a seasoned woman-person who writes on the internet, I’m no stranger to the occasional insult, sexually charged angry diatribe, or short-and-sweet slur. I took screenshots, forwarded it on to a groupchat with my best friends, and tried my hardest to laugh. While I typically don’t shy away from posting tamer messages on social media, I hesitated and decided this one could stay among friends. But as the minutes went on, I started feel more uneasy. I decided to disable my account, and for a little while just enjoy the company of my dogs, and only my dogs.

At this point, online dating sites are as ubiquitous as any other social network. According to the Pew Research Center, 15 percent of adults have reported using some kind of dating website or app, with the number of people 18–24 using them tripling since 2013. You’d be hard pressed to go to any bar, coffee shop, or college campus and not find someone lazily swiping through a parade of potential baes.

But to find someone who can actually make your heart (or other assorted organs) go pitter-pat on OkCupid, Tinder, Grindr, Bumble, Hinge, Scruff, Her, or any other matchmaking app, you need to fight past a fair number of not just duds, but occasionally scary jerks. That means ignoring the terrible, no good, very bad messages, and putting effort into the few good ones. And then for some people, wading through the slush pile is just too much.

Katie Kausch, 22, first downloaded Tinder while in college in New York City. She’d had some luck and met a partner that she happily dated for some time on the app, but said that, generally, she wasn’t swooned by the overtures from her would-be suitors—she was disgusted and seriously creeped out.

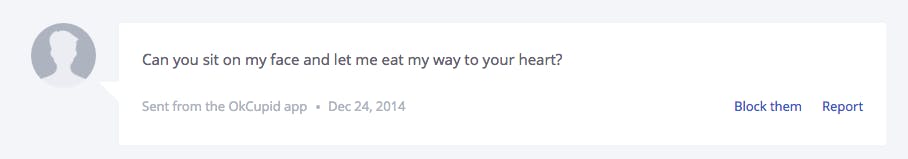

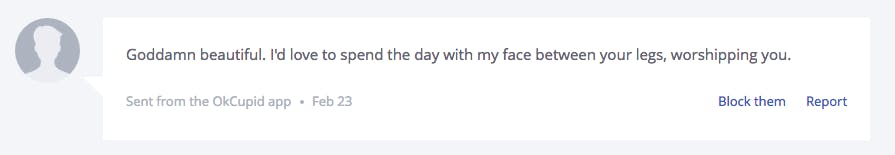

“I received some variation of ‘sit on my face’ very frequently,” she said. “Another notable line? One guy told me he couldn’t guarantee I wouldn’t end up at the bottom of the Hudson on our date. I quickly unmatched him.”

Her messages aren’t outliers. About 25 percent of teens have had to unfriend or block a person on social media due to uncomfortable flirting tactics, according to another Pew study. It’s disproportionately affecting young girls—with 35 percent of all teen girls surveyed making those flirt-blocking moves, as opposed to 16 percent of teen boys.

Other online daters I spoke with reported openers that were just as tactless as the former and as yikes-worthy as the latter. Whether they were on the receiving end of weirdly intimate requests for photos or regaled with unsolicited accounts of some rando’s darkest sexual fantasy, most of the online daters I spoke with had similar coping methods to mine: screenshot, send over to friends to compare battle stories, and then block the sender.

Most of the messages went ignored.

It seems that ignoring creeps is still the most common advice given to women, even by professionals. Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, says that ignoring, along with employing a liberal use of the delete button, is probably the best way (or at least the best of the easiest ways) to react to a barrage of uncomfortable or harassing messages.

“[Getting those messages] shouldn’t change your outlook about dating or yourself—because it isn’t about those things. It’s about their need for attention or their sense of inferiority,” Rutledge said. “Easier said than done, of course.”

According to Rutledge, dealing with online harassers requires folks to apply some of the same tactics they would when dealing with an entitled creep IRL. But “people with low self-esteem and low self-regulation,” she says, obviously think they can get away with more in an app than they would in the real world.

“Just like in real life, when people say rude things to you, when guys catcall from a construction sites, we’re programmed to disregard them,” Rutledge said. “We already know which kinds of levels of sexual harassment or bad behavior. We understand that context, we just need to develop a new way of thinking about it.”

“So you have to learn to get fast with the delete key or treat them as jokes with your friends, however it diffuses them and disempowers them,” she continued, “because by worrying about them or thinking that somehow it’s about you, it’s giving them a power they don’t warrant. If someone’s going to say something like that, the content is about them, it’s not about you.”

She adds that it might not be a bad idea to head off to a different app if harassment gets too intense—like you’d do when you leave a bar full of creeps: “If you’re seeing a lot of those kinds of comments, then that tells you about how that general site is managed, and you have to make an evaluation of what you want out of this.”

But like so much in our culture, telling the harassed to ignore, laugh, and walk away puts the onus on the harassed. For every cutting Instagram post featuring the “receipts” of some intolerable d-bag’s behavior, for every joke among friends, there’s someone who internalizes those messages, someone who walks away less comfortable in a space (digital or not) than they might’ve been before.

In Jessica Valenti’s memoir Sex Object, she gives a cutting assessment of the power play of mocking harassers, zeroing in on the flaws of such oft-repeated advice to ignore:

“Pretending these offenses roll off of our backs is strategic—don’t give them the f-cking satisfaction—but it isn’t the truth. You lose something along the way. Mocking the men who hurt us—as mockable as they are—starts to feel like acquiescing to the most condescending of catcalls, You look better when you smile,” Valenti writes. “Because even subversive sarcasm adds a cool-girl nonchalance, an updated, sharper version of the expectation that when be forever pleasant, even as we’re eating shit.”

Along with the feeling like you’re somehow giving in to the harassment by responding to it at all, there’s all that emotional and mental labor of deciding the “right” response—and that’s just as tiring.

“For every cutting Instagram post featuring the “receipts” of some intolerable d-bag’s behavior, for every joke among friends, there’s someone who internalizes those messages, someone who walks away less comfortable in a space than they might’ve been before.”

As Valenti writes: “This sort of posturing is a performance that requires strength I do not have anymore. Rolling with the punches and giving as good as we’re getting requires that we subsume our pain under a veneer of ‘I don’t give a shit.’ This inability to be vulnerable—the unwillingness to be victims, even if we are—doesn’t protect us, it just covers up the wreckage.”

But, perhaps that’s why that in-between step of sharing and talking about the weird and uncomfortable messages matters: You don’t necessarily have to laugh if that doesn’t make you feel better—but it still feels better than letting it seem normal and not talking about it at all.

“It’s a way of establishing a new norm,” Rutledge said. “It’s a way of enforcing what’s OK behavior or not-OK behavior.”

Emily May, co-founder and executive director of anti-harassment organization Hollaback (and the now award-winning online harassment reporting tool Heartmob) argues that sharing these experiences is actually a vital thing, and that taking some kind of action can actually have a healing effect.

Citing a study on online harassment from from the RAD campaign, craigconnects, and Lincoln Park Strategies, May says that the implications of online harassment aren’t all that different from harassment IRL: They can include lowered self-esteem, fear in their personal and professional lives, anxiety, depression, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“Online harassment is at the lower end of sexual violence because disproportionately we see it’s women who are impacted, especially women of color, targeted based on their identity—race, gender, sexuality, etc.,” May said. “The internet is a place where increasingly people need to be for professional, dating, and social reasons. Asking people to leave the internet is asking them to disconnect them from their people.”

So, rest assured, she doesn’t see online harassment as something you can just delete or unplug away. Instead, she says, online communities need to self-police, find ways to hold the platform accountable, and those who are able should keep telling their stories—which is low-key the reason Heartmob was created: to foster a built-in community that can offer resources, methods of self-care, and means of taking action for people who face online abuse and harassment.

“There are situations and times where you can’t deal with a sassy response and you just want to tune it out, and I think that’s OK, too,” she said. “For your own health and your own sanity, [it’s beneficial] to have some kind of other response in the world: whether it’s telling a friend, sharing in a group of empathetic people who understand what you’re going through, or even speaking out about harassment in a larger, political way.”

Particularly in online dating, the harassment can be sort of isolating—because it’s just you and the person sending you unsolicited garbage. However, May says it’s important to find ways to make sure you don’t feel alone and you don’t feel like you’re somehow welcoming this kind of behavior.

“For your own health and your own sanity, it’s beneficial to have some kind of other response to these messages: whether it’s telling a friend, sharing in a group of empathetic people or even speaking out about harassment in a larger, political way.”

“In online dating, we hear tons of stories of random penises being sent to you, or comments about you or your body that are totally unsolicited,” May said. “There’s this idea that by putting yourself out there for dating, you are saying: ‘I’m a sex object, consume me as you will’—but that’s not true. Opting into dating isn’t the same as opting into being treated as a sex object.”

After dealing with too many harassing messages—like near death threats—Kausch finally deleted her Tinder for good. She said the messages always made her feel “dirty,” as though she somehow deserved that kind of negative attention for putting herself out there on the apps. It didn’t help, she said, that some of her friends repeatedly told her that her discomfort wasn’t actually that big of a deal—that she should just ignore it.

“Some of my friends would tell me to stop overreacting—especially some men I know who use the same apps—but I no longer consider them friends,” she said. “My experiences are valid, and I don’t want to hang with people who belittle what makes me feel uncomfortable or unsafe… I’m looking for something more serious, and being sent these messages makes me feel not worthy of respect.”

She said she did try to fight back occasionally, drafting up a form letter to copy and paste into the particularly bad ones. She tried to remind these men that they weren’t just shouting into the void, but into the inbox of a human being with feelings.

“I started sending them this long, detailed message about sexual harassment and perpetuating rape culture, and pointing out that I call myself a feminist in my bio—so why are they even bothering?”

The results, as you’d probably imagine, varied: “One man was very apologetic—he’d forgotten real people were receiving these messages,” she said. “Another started yelling at me that I accused him of ‘sexual assault,’ even though I was very careful to only use the word ‘harass.’”

And “most were ‘neutral,’” she said, “’cause they just unmatched me right away.”

As for me, I reactivated my OkCupid and Tinder accounts for the first time a few weeks after that horrible, no good, very bad message. During a long night on the couch with two of my best friends and a few bottles of wine, it seemed like it was time to gaze back into the abyss.

Glancing at the inbox, I realized the match algorithm tended to help me opt-out of reading the messages that rub me the wrong way. I know they’re there, of course—one intrepid suitor asked if I really knew how to use my mouth, another wanted to know why I think I’m “too good to reply” to him with my “fat nose,” a third who tried three times to “chat” wanted me to know I was a “bitch.”

I’ll admit: In those moments, surrounded by good wine and better friends, it was much easier to laugh.

Katherine Speller is a writer and journalist who unapologetically screenshots 90% of her text communications and is likely to try (and fail) to sand off her fingerprints someday. She’s low-key only bothering with online dating to meet more dogs.