“What do you think about the monkey?” a grinning volunteer, all teeth and gums and wiry hair, asked me.

In any other setting the question might’ve been nonsensical. But here at Wikimania, there was no doubt as to what it referred to: a certain crested black macaque.

This weekend, London’s Barbican Centre opened its arms to Wikimania, the annual three-day event dedicated to Wikipedia and its associated projects. Part-festival and part-industry conference, it was characterized this year by introspection and serious deliberation over the online encyclopedia’s place in the world, 10 years after its inception—a large part of which focused on, yes, the monkey.

One of Wikimania’s biggest news items was actually revealed at a press conference held two days before the beginning of the event. The Wikimedia Foundation, the non-profit organizing body behind Wikipedia, revealed its first-ever transparency report. The report disclosed 56 requests for user data over the past two years, along with 304 “content removal requests.”

But it was only one of these requests that has really stuck in the public imagination.

British photographer David Slater had gone on holiday to Indonesia in 2011. While there, a crested black macaque stole his camera, clicked wildly, and—as luck would have it—snapped a pretty decent selfie. Pleased with the result, Slater returned home and enjoyed minor success from the photo, before discovering that someone had uploaded it to Wikipedia.

Annoyed that someone had uploaded his photo without permission, Slater asked the site to take it down—but the community-based encyclopaedia refused, on the grounds he didn’t own the copyright. The monkey took the photo, and as a non-human animal, Wikipedians reasoned it was unable to hold copyright—letting the photo fall into the public domain.

After this surreal interpretation of copyright law was brought to wider attention in the Transparency Report, the story exploded. It made the front-page of national newspapers, with write-ups by the BBC, The Guardian, the Daily Mail and more, to the delight of Wikimania’s organisers.

“We didn’t have to do any work to publicize this conference,” joked coordinator and Wikimedia UK employee Ed Saperia, “because we’re in the news every day anyway!”

For the most part, the more than 2,000 Wikipedians in attendance embraced the monkey as a symbol of the conference, making knowing references at panels and printing out the photo on posters. Not everyone was happy with the conference’s poster child, however. In his opening remarks, Wikipedia founder and self-described “constitutional monarch,” Jimmy Wales, said he found the response from the media “disappointing,” in light of other topical issues discussed at Wikimania.

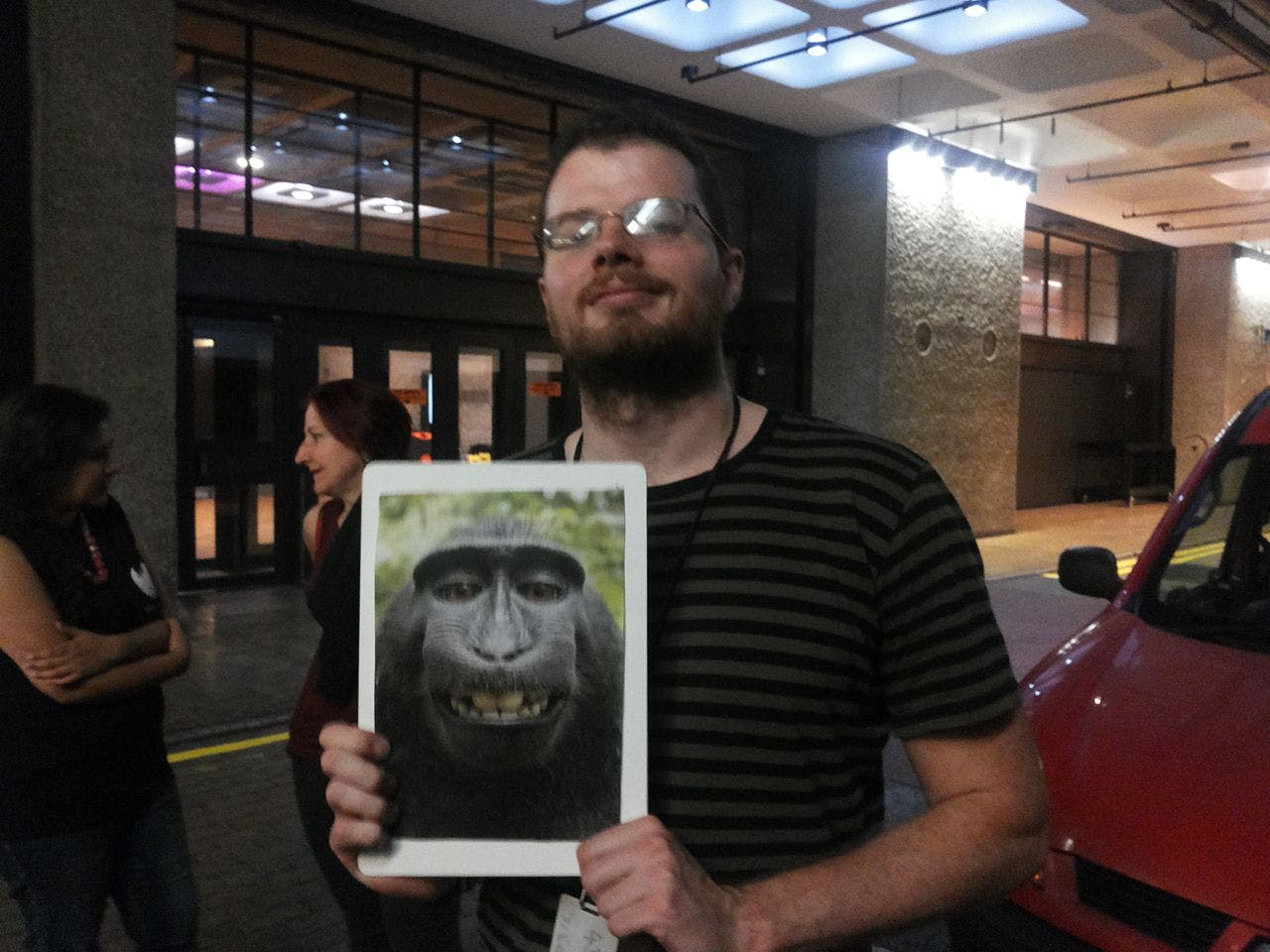

A “monkey selfie” placard that became the focus on numerous “human selfies” over the weekend. Photo via Romaine / Wikimedia Commons (CC 1.0)

A “monkey selfie” placard that became the focus on numerous “human selfies” over the weekend. Photo via Romaine / Wikimedia Commons (CC 1.0)

These were numerous, from the recent appointment of Lila Tretikov to the position of Executive Director at the Wikimedia Foundation, to the ongoing debate over the European “right to be forgotten,” and Wikipedia Zero.

But beyond the hot topics, dozens of user-created panels and round-tables also discussed and debated every aspect of Wikipedia life throughout the weekend. Some issues, like the role and ethics of paid editing in Wikipedia, were relatively accessible to outsiders; others, like the “exchange of deletion/review processes,” or the “value of inclusionism,” remained arcane and inaccessible. It was, after all, an industry conference, and, as a roll call by Jimmy Wales demonstrated, some members have spent a full decade of their lives working on the project.

Like Slater’s monkey misfortune, the “right to be forgotten” hung heavy over the conference—a reminder that there exists a wider world outside the often Byzantine internal politics of the Wikipedia community. The result of a ruling by the European Court of Justice earlier this year, the “right to be forgotten” stipulates that European Union citizens have the right to have “out-dated” or “irrelevant” material removed from online search results, even if the information remains factually accurate.

Lila Tretikov addresses the audience at Wikimania 2014’s opening ceremony. Photo via Rock drum / Creative Commons (CC 4.0)

The legal decision has pitted privacy campaigners against free speech advocates. Wales has angrily railed against it, likening it to “censoring history.” Prior to the conference, the Wikimedia Foundation officially condemned the ruling for “undermining the world’s ability to freely access accurate and verifiable records about individuals and events.”

The Foundation has also established a dedicated page for listing all notices of page removals they receive from search engine. And Tretikov condemned the law during the opening ceremony as passing “the writing of history to corporations.”

The Wikipedia community may view the “right to be forgotten” as a new kind of existential threat to its mission to provide free and open knowledge for everyone. But Wikipedians still found a great deal to celebrate over the weekend, and chief among these was Wikipedia Zero.

The collaborative project with mobile operators around the world provides Wikipedia for free to those who can’t afford to pay Internet data charges in certain parts of the world. The Foundation’s head of engineering, Erik Moller, told the Guardian that it as many as 350 million subscribers may be able to access Wikipedia with the expanding service.

The project, which began with partnerships in Malaysia in 2012, is part of a renewed focus on the developing world and the hundreds of millions of people expected to come online for the first time over the coming years.

The conference also saw the public introduction of the Russian-born Tretikov, the Foundation’s new executive director, hired only a few months prior after more than a year of searching. Tretikov is a product of the Soviet-era “glasnost” period, in which then-President Mikhail Gorbachev called for greater government openness and transparency. The 36-year old stressed in her opening remarks that “there’s another billion people coming online, and [Wikipedia] needs to be there for them.”

She reinforced this message In her keynote speech on Saturday, warning about the dangers of complacency. “The biggest risk next is actually doing nothing,” she said.

Tretikov’s introduction to Wikipedia has not been painless, however, with some criticizing her relative inexperience with the community. Her recent admission that she had only made her first edit on English-language Wikipedia after accepting the position prompted a backlash, with one editor calling her an “amateur.”

Her keynote speech was broad, but understandably light on specifics, and enjoyed a small standing ovation. Speaking to attendees afterwards, it was clear that many remain to be convinced. One Wikipedian told me that “product placement” was just around the corner, a reference to Tretikov’s corporate background at places like Sun Microsystems and SugarCRM.

She also bring 18 years of open-source software experience under her belt. But Wikipedia’s community is famously argumentative, and if she can’t rally support in the months to come then she may be in for an uphill battle.

When Wales took the stage Sunday night to close the conference, he challenged this strain of acrimony head on. To resounding cheers, he told the assembled audience in Barbican Hall that the breed of annoying, confrontational Wikipedian (even if they contribute good content) simply “costs more than they’re worth,” and need to leave the community.

Jimmy Wales on the final night of Wikimania 2014. Photo via Sebastiaan ter Burg / Wikimedia Commons (CC 2.0)

Historically, Wales’ “State of the Wiki” address has been peppered with statistics and factoids, but he eschewed them this year, with the exception of one: That Wikipedia, according to a YouGov poll, is now trusted by British people more than any news source, and is second only in credibility to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

“I’m not going to rest until they trust us more than they ever trusted Encyclopedia Britannica in the past,” Wales declared.

In his speech, Wales laid out a case for “moral ambitiousness,” calling on Wikipedians not to center the debate around the bear minimum standards of behaviour—”promoting a race to the bottom”—but instead to extoll certain virtues, “kindness,” “generosity,” and “forgiveness,” among them.

In the midst of such soul-searching, one can hardly blame the Wikipedia community for reveling in the media curiosity that was the “monkey selfie.” After all, when Tretikov asked her audience how they imagine the Internet in another 10 years she might have been speaking rhetorically—but despite the answers Wikipedians came together to formulate, the big questions remain.

Photo via Tim Strater (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed