The immigration debate has always been fierce, but President Donald Trump’s State of the Union vow to end “chain migration” has ignited an already-heated fight over immigration reform in Congress—and part of it stems from his word choice.

What is chain migration?

In the United States, U.S. citizens and permanent residents are allowed to sponsor their close non-citizen family members for a green card. Immigration hardliners refer to this as “chain migration” and see it as a loophole that allows an immigrant newly admitted to the United States the ability to sponsor an endless “chain” of unskilled, non-English speaking relatives. Chain migration forms the crux of U.S. immigration policy, accounting for nearly two-thirds of new green cards issued every year, according to Department of Homeland Security statistics. Of the 990,553 foreign nationals admitted to the United States as permanent residents in 2013, nearly 649,763 of them, or 68 percent, were admitted due to family ties.

“Chain migration” became a target of Trump and his nativist base following a failed New York City subway bombing by 27-year-old Bangladesh national Akayad Ullah in December. Ullah, who had come to the United States in 2011, was a “chain migrant” and legal green card holder.

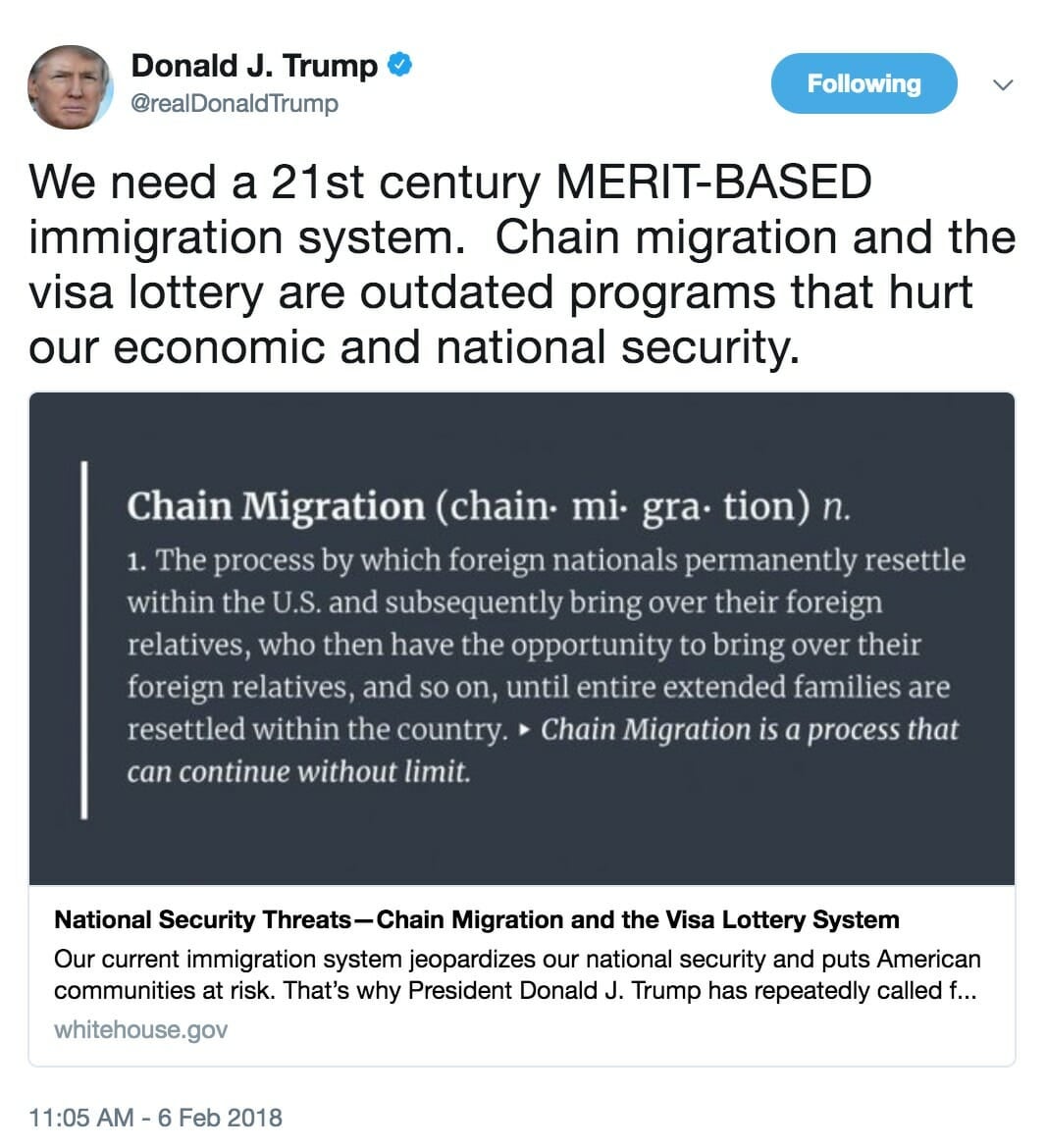

President Trump has tried to normalize the term “chain migration,” going so far as to tweet out a definition for it, though it’s unclear where it came from.

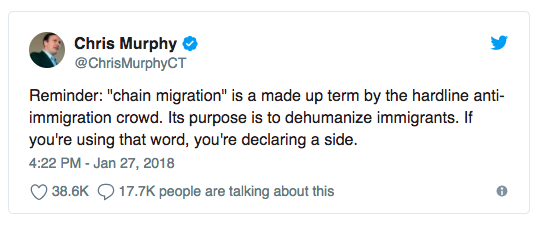

Immigration rights advocates have deemed the term “chain migration” offensive and prefer the term “family reunification.”

“AILA’s position is that the term “chain migration” is offensive and is being utilized by the [Trump] administration and some members of Congress to mislead, and even scare, the public into believing that our immigration system allows massive numbers of extended relatives to gain immigration status in the United States,” wrote Diane Rish, associate director of government relations at the American Immigration Lawyers Association in an email to the Daily Dot.

Added Patrice Lawrence, national policy and advocacy director from Undocublack, an immigrant rights group, chain migration “is a term invented to dehumanize, belittle and reduce immigrants to lesser human beings. The term reminds me of herding cattle or more prominently being chained together the way slaves were forced upon ships that traversed the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea hundreds of years ago. It is a callous term.”

Rish added that the term chain migration appeals to nativists who worry that immigrants are “taking over the country.”

“The reality is that family-based visas are only available to a limited group of close family members, and most of them are subjected to wait times of many years, often decades, before a visa even becomes available,” Rish wrote.

But critics of so-called “chain migration” maintain that the U.S. is losing out on highly skilled immigrants by emphasizing family ties instead. The United States’ family-based immigration policy is different from other Western nations, such as Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, which use point-based immigration systems that prioritize skilled immigrants. In the United States, it’s far more common to be sponsored for a visa by your family member rather than your employer. The Immigration Naturalization Service (INS) allocates 140,000 employment-based green cards per year, which, in 2014, made up roughly 14 percent of the total green cards awarded.

The U.S. made the move towards family-based immigration several decades ago with the passage of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act, or INA. Prior to the 1952 INA, the U.S. relied on a quota-based immigration system that limited immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe and completely banned immigrants from Asian and Arab countries. The 1952 law put new quotas in place and still put a preference on certain racial and ethnic groups, but it also made a key change that shapes U.S. immigration policy to this day. It prioritized immigrants who were immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Immigrants with American relatives were not subject to the quotas put in place by the new law, a policy that remains in effect to this day.

Despite the fact that family reunification has been a part of U.S. immigration policy for more than 50 years, there are still plenty of misconceptions about the system. Here are four myths about the so-called policy of “chain migration.”

4 myths about “chain migration,” debunked

1) Chain migration allows immigrants to bring over extended family

Former foreign service officer Dave Seminara said the following in an op-ed in the Hill on chain migration: “I have five brothers and if I were to move to, say, Australia, I would never assume that all six of us, plus my parents, should be entitled to live there. But that’s exactly what U.S. law offers migrants.”

But Rish from AILA calls Seminara’s statement “blatantly inaccurate.” Chain migration only allows U.S. citizens, not migrants, to sponsor their spouses and unmarried children for green cards. Americans can also petition for green cards for their siblings, parents, and married children, but it is a long and arduous process that can take more than a decade. U.S. citizens must prove that the family relationship is real, meet certain income requirements, and submit a signed affidavit of support stating that the sponsor will be financially responsible for the family member.

“Each prospective immigrant is subjected to extensive background and security checks to screen for ineligibilities, including criminal, national security, health-related, and other inadmissibility grounds,” wrote Rish.

In most cases, prospective applicants must appear in-person for an interview at a local United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) field office prior to approval of the green card.

2) Chain migration is quicker and easier than other paths to citizenship

Far from being an open-door immigration policy, the current backlog of visa applications has made the average wait time to merely apply for a family-based green card more than several years. Applicants from China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines face longer wait times.

If you’re the Polish or Bangladeshi brother of an American citizen, you can now begin to apply for your green card if your priority date—the day the petition was filed—was before June 2004, according to State Department figures.

READ MORE:

- What is universal healthcare?

- Untangling antifa, the controversial protest group at war with the alt-right

- What is socialism, really?

3) DACA recipients will bring their parents and other family members in through chain migration

A beneficiary of not one but two immigration programs, it’s Jeff Session’s worst nightmare. Some Republicans have warned of the potential of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, once they’ve received U.S. citizenship, using family reunification to sponsor their parents and other family members.

“So the number on DACA is 800,000, but every one person can bring in their entire extended family once they reach a certain status. So it’s three or four million, right?” said Rep. Dave Brat (R-Va.), an immigration hardliner, in an interview with NBC’s Chuck Todd.

But hordes of Dreamers sponsoring millions of other immigrants simply hasn’t happened—and can’t happen.

There are nearly 800,000 DACA recipients in the United States. To be approved for DACA, a Dreamer had to have entered the United States before they were 16 years old. Given their young age, it’s unlikely they’ll have spouses or unmarried children in their home country they wish to sponsor. Their siblings are likely DACA recipients themselves. The parents of DACA recipients are disqualified from applying for a green card for 10 years due to entering the country illegally. Add that delay to the additional decades-long approval process to apply for your green card and the potential for parents of DACA recipients to suddenly swell in number appear very slim indeed.

READ MORE:

- The best political podcasts to keep you informed

- Understanding the 25th Amendment, the unlikely path to removing Trump from office

- Who’s going to challenge Trump in 2020? Here are the super-early contenders

4) Illegal immigrants benefit from chain migration

Critics of family reunification say it allows relatives of American citizens to enter the country illegally. NumbersUSA, an anti-immigration group founded by white supremacist John Tanton, say that many relatives of American citizens may feel they are entitled to U.S. citizenship and decide to come here illegally.

From the Numbers USA website:

“Because these distant relatives may eventually obtain a visa on the basis of the extended relationship, they come to see immigration as a right or entitlement. When they realize that they may, in fact, have to wait years for a visa to become available because of annual caps and per-country limits on several of the family-based immigration categories, many decide to come illegally, despite that the law requires them to wait in the home country.”

But this simply isn’t true, considering that entering the country illegally disqualifies someone from applying for a visa to the United States for a length of time.

Rish of AILA dismissed the fears of critics who believe family reunification will result in a flood of illegal immigrants. Immigrants who are illegally in the United States or have overstayed their visa are typically not eligible to become green card holders.

“Such critics do not have a complete understanding of the U.S. immigration system, which typically prohibits or poses serious hurdles to an individual who has been in the United States illegally from obtaining a green card. Thus, such fears that people will remain in the United States and wait out the date until their green card application is approved does not align with how the immigration system works,” Rish said.