When Pax Jones answers the phone on a lazy Monday night, it’s clear from the sound of their voice that they are annoyed. The 23-year-old is getting stared down by some locals in Querétaro, Mexico, where they’re visiting. “I’m pissed off,” they tell the Daily Dot. “I’m sitting down in a mall and people are staring at me like I’m a monkey in a zoo.”

This overt kind of othering isn’t new to Jones, who identifies as a non-binary, Black femme. In fact, the hyper-visibility and simultaneous erasure—not to mention the violence—that follows dark-skinned people of color is why they created the viral movement #UnfairandLovely in the first place.

And it’s why they are fighting to reclaim it.

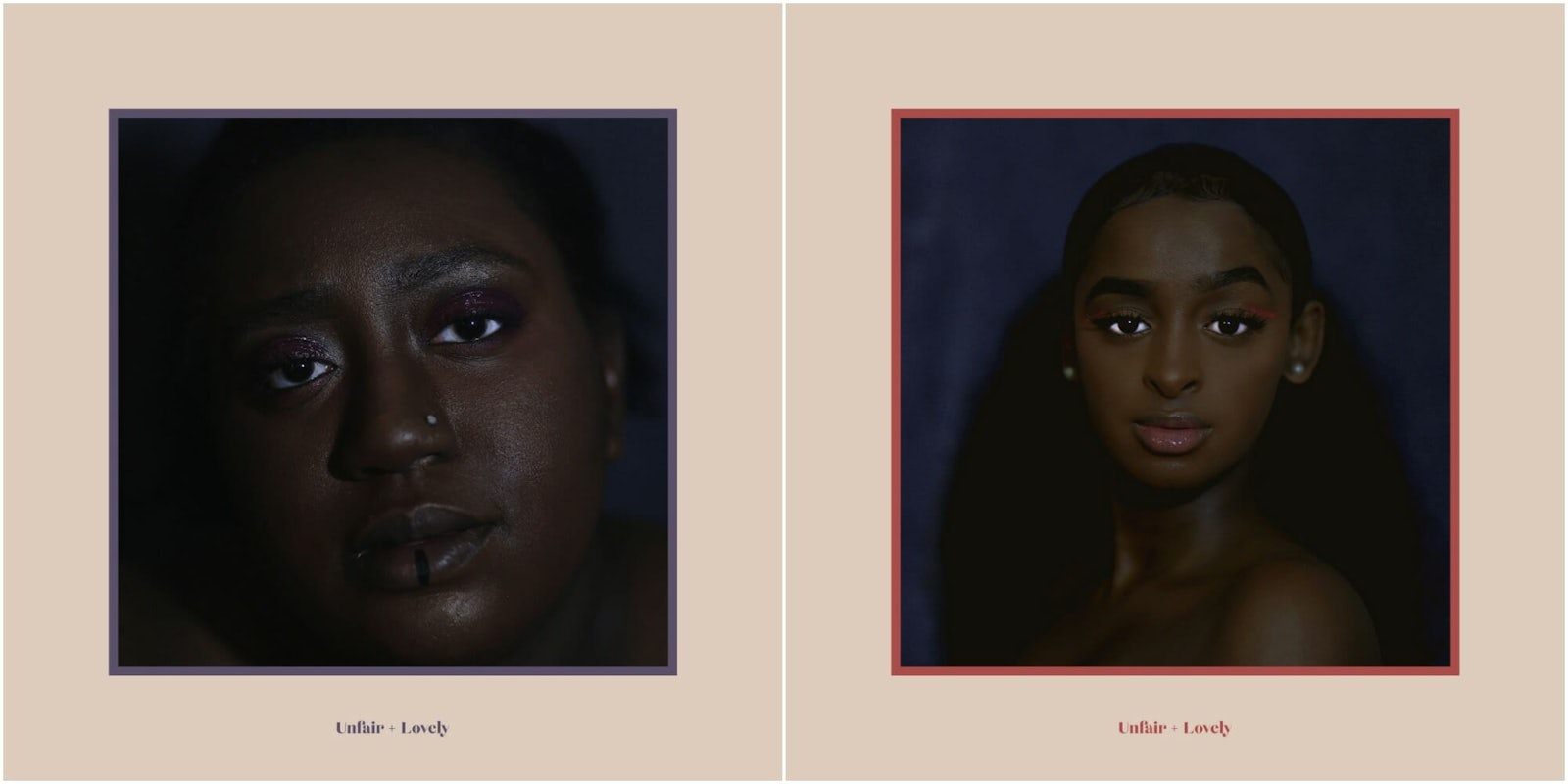

Jones, a photographer, founded the movement by accident. In December 2015, they decided to center a photo series on the global impact of colorism and posted the photos on Tumblr. The photos went viral almost overnight. Listening to the wise advice of a friend, Jones slapped on the hashtag “#UnfairandLovely,” and suddenly the social media movement was born. Hundreds, then thousands, of dark-skinned women from around the world began posting photos of themselves using the hashtag.

Jones’ aim was to fight colorism which, in simple terms, can be defined as the preferential treatment lighter people of color receive over their darker-skinned peers. The phrase “Unfair and Lovely” itself was inspired by the skin lightening cream “Fair and Lovely,” popular in Asian communities. Many of the photos Jones included in their initial project featured friends, including their partner at the time who is a dark-skinned Tamil woman.The act of skin bleaching and lightening isn’t specific to Asian cultures, though.

“Colorism is much more complicated than we think it is. It intersects a lot of different points of identity,” Jones says. “That’s really what my goal was, to show that there is this thing we’re all talking about independently, so let’s talk about it together, and let’s also talk about the nuance.”

As the selfies rolled in, Jones was stunned that so many people immediately connected to the movement, proving the need for discussions centered around colorism. But the rapid pace at which it spread, and the number of people participating without ever having seen their photos made Jones uneasy. “I was excited that something was happening and people were paying attention, but it kind of felt strange,” Jones says. “That hashtag is obviously not a photo series. To me, it was a single concept, and for other people, it’s definitely not. So I felt like I was doing something wrong.”

The movement exploded in 2016 and media outlets quickly picked up the story, but it slowly became clear that the media coverage and engagement in Unfair and Lovely was not as inclusive as Jones originally intended. An early article labeled it as a movement specifically for dark-skinned South Asian women.

The article was written by two freshmen for the student-run magazine at Jones’ college, both of whom are South Asian. One writer says that looking back, she understands how the article failed the movement. “If I could go back, I would want a Black person writing the article,” Zoya Zia, now a junior, tells the Daily Dot. “Having Pax as more of the main focus of the interview would have been better, but just not erasing people who are responsible for the vision.”

The other writer Rachana Jadala, who now works on the #UnfairandLovely team to strategize how they can include other communities of color, says the first article “went the way it did because the visuals were South Asian women, so that’s the superficial level people engaged with.”

Eventually, the story got picked up by BuzzFeed, the BBC, USA Today, and several other major outlets—and each of those stories contained the same mischaracterization.

“My biggest issue is when I read any sort of article and the center of it was ‘this movement for dark-skinned South Asian women.’ Not only was that misinformation, but it carried over to other places,” Jones explains. “I remember very distinctly seeing someone having a conversation saying, ‘Why are Black girls trying to come into this hashtag? You guys already have #BlackGirlMagic, you already have this, you already have that, this isn’t for you.’ And when I saw that, I was just like, ‘OK, well, this is over with.’”

On Twitter and Instagram, Jones attempted to mitigate the misunderstanding by correcting people, but it seemed like the misplaced buzz had already snowballed. They watched as others commodified the phrase, slapping it on merchandise and selling their movement via woke T-shirts. Someone even created an Instagram using the slogan only featuring South Asian women. Jones even reached out to the account and to Instagram itself to have it taken down for copyright infringement, but was unsuccessful. The Instagram is still active today with more than 10,000 followers.

Ironically, the thing that made their movement so successful, a hashtag, is the same thing that swept the movement out from under Jones’ feet. Feeling disappointed and out of control forced Jones to step away from the project. “It got to the point where I had to remind myself that I even did anything. I think it definitely made me feel insignificant to say the absolute least,” Jones says. “People, especially Black femmes for whatever reason, always have to remind themselves that they did do work. Even though people are going to convince us that we didn’t.”

Jones never planned to return after leaving the movement. In fact, they wanted nothing to do with it. But a year after walking away, they noticed that people were still using the hashtag, that BuzzFeed was still producing content about the movement, and that the phrase Unfair and Lovely still resonated with so many dark-skinned people around the world. It was then Jones decided to reclaim it.

They got a lawyer, paid for a trademark, and started coming up with ideas for a relaunch. Two years after the movement’s inception, on Jan. 19, Jones and their team launched a new website with new #UnfairandLovely branding. “I gave myself that initial push and that initial push was claiming my ownership formally,” Jones says. “The way that I’m reclaiming is rebranding it by ingraining what I wanted to be there from the jump. Basically re-baking the cake and adding my own ingredients instead of letting other people come into the kitchen.”

The new movement is focused on education: first through Twitter, and later through a curriculum and learning materials Jones intends to provide to people outside of the internet. “Step one is education, because there’s still so many people who have no idea what it is even though they’re experiencing it,” Jones explains. “The target is all people of color who have the potential to experience colorism. We view colorism as a global phenomenon. We want the reach to be global.”

The #UnfairandLovely team is also taking more rigorous steps to make sure all dark-skinned people of color feel included. “We want #UnfairandLovely to be focused on the most marginalized bodies,” says Sarah Ogunmuyiwa, who helps create social media content for the movement. “We want to see fat bodies, and trans women’s bodies, and Black girls’ bodies. If we have photo projects, we want to make sure we have not just cis, heteronormative femmes. We want our projects to focus on unconventional beauty and uplift the voices of people who don’t usually get heard.”

When asked what advice they have for other young Black innovators, many of whom are also at risk of having their ideas taken and misconstrued online, Jones says they should never be afraid to claim and reclaim what belongs to them.

“At some point, you have to realize that if these people wanted to give you whatever it is you’re asking for, you wouldn’t have to ask for it in the first place,” Jones says. “So stop asking for these things that are yours, and take them.”