Opinion

Trans/Sex is a column about trans peoples’ relationships with love, sex, and their bodies. Have a topic suggestion? Contact Ana Valens at avalens@dailydot.com or @acvalens on Twitter.

…

Here are some trans erotica ideas I’ve been kicking around since releasing my first game last year:

- A robot trans girl and her trans lesbian creator realize their attraction to each other during an internal “calibration” process

- A lesbian Medusa seduces and fucks an Athenian trans woman warrior who both fears and desires her

- A gigantic cis woman devours a small, timid, yet masochistically eager trans girl

- Two lesbians rip and tear into each other’s bodies, delighting in one another’s bloody flesh until nothing remains

These ideas aren’t meant to be edgy, weird, or push boundaries. I don’t want to make people feel uncomfortable or trigger a trauma response. I want to write these because they give me butterflies in my tummy. I love monstrous women with a passion that hasn’t gone away in 25 years and probably won’t in the next 25. Trans feminine art often includes elements of body horror, sometimes alongside suffocating, even brutal levels of physical intimacy. Fear and obsession over how our bodies will be perceived intersect with deep, traumatic desires to “fit in” with society. I turn to erotica to explore these gruesome, violent, self-destructive cravings.

But every time I sit down to write a new fiction story, I get anxious. Many young queer people online do not respond well to difficult and uncomfortable sexual material, like guro porn or monstrous lesbians who use force to get what they want. This is laughable to me. I grew up on sadomasochistic fantasies of giant women destroying cities and devouring tiny men, and as of yet, I have not actually turned into a 200-foot woman, let alone destroyed an entire city. But that doesn’t make the danger of retribution any less real. Society deems trans feminine people as boundary violators, which means trans artists playing with erotic violence and horrific desires become the inconvenient problem that needs to be “eliminated” for other genders’ safety.

“I’m not gonna beat around the bush I WILL do whatever I can to stop these people and if it means hurting them, isolating them, or taking away their source of income, I’ll do it!” one Twitter user wrote in a viral thread. “If people actively participate in this culture, they’re fair game. We need to protect our community. […] this is about intracommunity safety, eliminating people who hurt and threaten MY communities from within.”

Before you can eliminate a person, you eliminate their art. And there’s no better way to do that than through a harassment campaign.

Earlier this month, Clarkesworld magazine published Isabel Fall’s short story “I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter,” a work of trans satire from a little-known writer. Within days, Clarkesworld pulled the story at Fall’s request amid enormous backlash from parts of the trans community. An archived version is available here.

Fall’s story follows a “somatic female” whose “attack helicopter” gender identity is instituted after “tactical-role gender reassignment.” It’s a clever premise that plays with genderfuckery and body horror while touching on many aspects of transness within capitalism, the American military-industrial complex, and everyday life. It also describes the insecurities trans women experience with their genders and bodies without outright making fun of us for having them.

“Some people say that there is no gender, that it is a postmodern construct, that in fact there are only man and woman and a few marginal confusions. To those people I ask: if your body-fact is enough to establish your gender, you would willingly wear bright dresses and cry at movies, wouldn’t you?” Fall’s titular attack helicopter says. “Have you ever guarded anything so vigilantly as you protect yourself against the shame of gender-wrong? The same force that keeps you from gender-wrong is the force that keeps me from fucking up.”

Many readers assumed the story could only come from a bigot, a right-wing troll, or a cis person because “I sexually identify as an Attack Helicopter” is a notorious transphobic meme. But the meme is the point. After the story was pulled, editor Neil Clarke confirmed that Fall “honestly and very personally wanted to take away some of the power of that very hurtful meme.” This was lost on a huge portion of Fall’s detractors.

“I genuinely don’t understand the criticism of the story but it’s hard to find what the original criticism was, now. It seems like everything is meta-criticism at this point, and I can’t really tell where the original critiques were coming from, beyond a discomfort with the title of the story,” trans comic artist Carta Monir told me. “It feels like this story was the victim of some kind of avalanche effect that I don’t really understand.”

Avalanches have fallen on marginalized artists for quite some time. Last year, Snotgirl artist Leslie Hung helped an artist creating Devil May Cry yaoi fanart depicting adult characters Dante and Nero together. In the series’ canon, Dante is Nero’s uncle, making the fan art about an incestuous relationship. The fan world quickly became divided over Hung, leading her to, as she later put it, get “canceled”.

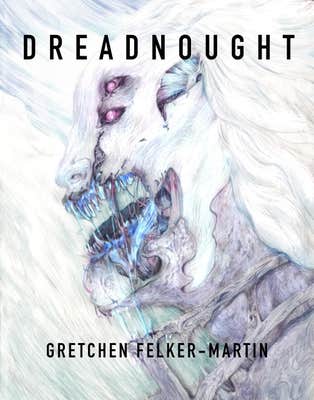

Horror author and film critic Gretchen Felker-Martin spoke out shortly after with an essay called “I Don’t Wanna Grow Up (And Neither Can You).”. In it, she explores how a group of left-leaning millennials and Gen Zers are policing art that depicts “pedophilia, self-harm, intimate partner abuse, necrophilia, violence against children,” and other sensitive topics. These critics only approve art that depicts taboo as fundamentally bad, as if, for example, your average reader needs a reminder that a professor-student lesbian erotica story should not be reenacted with your real students.

“There’s nothing wrong with escapism. There’s nothing wrong with not wanting to or not being able to engage with art about horrific things. The problem begins when you look at the people who can, who need to, and decide that they can’t either, that they’re going to have to bend to your worldview or you’ll call them pedophiles and Nazis and incest apologists and run them out of town,” Felker-Martin writes.

Felker-Martin knows first-hand why “messy queer art” is so important. Much of her own work deals with “trauma and misery and self-loathing and a bunch of other stuff it absolutely fucking sucks to lug around with you through life,” she told me. Uncomfortable art lets her reckon with the “rotten, rancid parts of being queer,” including internalized hatred of oneself. And just as her own art is complicated, so are her detractors. She theorizes an “admixture of repression, self-infantilization, transmisogyny, and assimilationism” motivate their actions. This leads to a childlike obsession with art stripped of queer pain, making these young viewers perfect consumers for corporate media churned out by Disney, Cartoon Network, and Netflix.

“You’ve got increasingly sexless, homogenized mass media to which an exhausted public has gravitated en masse, a country culturally obsessed with security and punishment, a sense that the people above us ruining our lives are basically untouchable; it creates this sort of hopeless, like, destrudo, like a death drive to destroy as much as you possibly can,” Felker-Martin said. “And I think at a very basic level, the people participating in these harassment campaigns are expressing misogyny and transmisogyny that they’ve repressed within themselves and which they can ‘safely’ vent by attacking visible deviants.”

Monir, on the other hand, points to horizontal violence among trans women, as she believes some of our trans sisters become so overwhelmed with their powerlessness against large discriminatory social structures that they instead “turn to things that they do have power over.” Self-hatred, lack of large-scale community spaces, geographical social isolation from an IRL queer community, and the growing pains of young adult life further enable “the meanest kinds of vitriol” among trans women.

Monir doesn’t approve of these people’s behavior, and she warns people of color (particularly trans women of color) are “more vulnerable to harsh and unfair criticism.” But it’s not as if Monir simply wants to reverse the power dynamic over these young queers. She cares about their wellbeing and thinks it’s important not to fight traumatizing behavior with traumatizing behavior.

“I think, ultimately, there’s a question of what it means to be hurt by a work of art. There are plenty of things that I’ve read or seen that have caused me distress, personally, but there’s a pretty big difference between causing me personal distress and causing harm on a larger, societal level,” Monir told me. “People take art and they assign personal meanings to it, and they’ll look at it and think about it in ways that we could never have anticipated. The important thing is making art that feels genuine and honest to ourselves, and trusting our readers and audiences to look at whatever we’re presenting in good faith.”

The queer community’s strength lies in its weirdness, its nonconformity, its comfort with the uncomfortable, its power to heal from pain (or make pain into pleasure). When we start policing what artwork is valid and what must be banned, Felker-Martin said, we make it “harder for queer people to earn a living, harder for us to connect with each other on a personal level,” and “harder for us to feel safe in public and even with each other.” Even if you don’t enjoy writers like Felker-Martin, artists like Monir, or satirists like Fall, they unconditionally deserve the right to create art.

“I frequently have to remind myself that just because something is bad isn’t enough reason for me to tear it apart in public, especially if it’ll only be seen by like a maximum of a few dozen people,” Monir said. “I’m making work for the pleasure of making it, with the hope that it’ll reach other people and make them feel things. I know that my peers are doing the same.”

READ MORE:

- In 2019, I learned why Pride isn’t Pride without kink

- Andrea Long Chu’s ‘Females’ signs up for cisnormativity

- Porn has a trans representation problem

- How can we create more inclusive sex education offline?

Editor’s note: An additional quote by Gretchen Felker-Martin has been added for clarity and context.