You don’t have to tell Andrew Golis about how bad internet comments are—he already knows. Golis has worked as an editor for Talking Points Memo, Yahoo, and the Atlantic, and he’s married to feminist author Jessica Valenti. When the Guardian commissioned a study of 70 million comments left on its site, it found that the person who attracted the most abusive comments was Valenti.

“For all the progress women have made, there’s always an online comment section or forum somewhere to remind us that, when given anonymity and a keyboard, some men will use the opportunity to harass and threaten,” Valenti wrote about the dubious honor in her column for the Guardian.

As a result of harassment, trolls, and spam bots, many sites (including this one) have opted to shut down their comments sections. So it might seem counter-intuitive that Golis, founder and CEO of This, is suddenly interested in starting one.

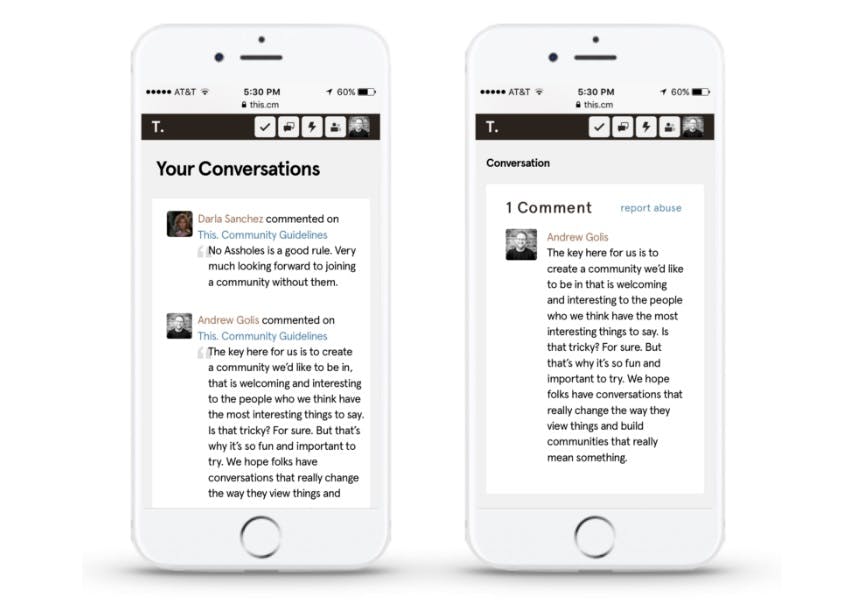

This is a social sharing site that allows users to post one link a day, whether its journalism, entertainment, or arts focused. It has been up and running for over a year without a comments section, but on June 13, it announced in a blog post: “Comments are usually garbage. We’re adding comments to This!”

Possibly the greatest guideline I’ve ever seen on a website’s TOS. Bravo @THISdotcm pic.twitter.com/xd6mhEhvgS

— Nick Graham (@thenickgraham) June 13, 2016

The comments section on This is members-only—only those who are members can share articles or post comments. Posters can also opt out of a comments section on their link, too, if they like.

Golis’s goal, however, is to build conversations from comments and build communities from those conversations. Which is how comment sections work at their best—yet that’s been harder and harder to achieve and maintain over the years.

If you’re older than 1o, you might remember internet communities where the comments were actually fun and fostered lively debates. As a teen, I spent a lot of time in internet chat rooms and then later made friends in the comments section of my own blog and in safer comment spaces like the Hairpin and the Toast. I’ve also been part of many Facebook forums, though each one seems to go sour after a year or two.

“The person who I am on Twitter is jokey, knowing. And that’s not the person who my friends would say I am talking about a book I just read. But that’s the person who is the best at getting retweets or faves.”

But not all sections are created equal (or moderated equally), and anger in a thread often begets more anger. Experts attribute online hostility to anonymity and the immediacy of commenting. No one interrupts you when you are typing furiously on your keyboard, after all. There are few repercussions that affect you in your daily life when you call a woman a “fat, ugly bitch” on Twitter.

Then there’s the hard work of keeping the comments section clean. For five years, I worked as a comment moderator for a love and sex site. Every morning, I would wake, up drink coffee, and begin sorting through comments. By the time 9am rolled around, I was already trash heaps’ deep in dick references.

And that’s if a site even has a dedicated comment moderator. Many rely on filtering software and community reporting, and both means are unreliable. Additionally, a lot of internet publishers believe that comments of any kind show advertisers what a robust community they have. I was often told to err on the side of leaving inflammatory comments in, just to catalyze discussion and increase traffic.

Golis believes the loss of internet comment culture can be attributed in part to the growth of online media. Which, as he explains, transformed small “web islands of sub communities to these big centralized platforms,” he told the Daily Dot. “So because of that, there have been duel effects. So on Twitter or other places, you had better conversations than anything you’d see on a certain site. But as those platforms have gotten bigger, the people who have been active on them have gotten bigger and bigger followings.” This, Golis notes, has resulted in a flood of toxicity.

Golis also argues that social media isn’t conducive to deeply thought-out arguments. He says that the person he is on Twitter is a lot different than the person he is in a one-on-one conversation. “The person who I am on Twitter, by the mode that it sets me up as, is jokey, knowing, and I hate to use the internet cliche, but snarky. And that’s not the person who my friends would say I am sitting at the bar, talking about a book I just read. But that’s the person who is the best at getting retweets or faves.”

This is hoping to smooth over the sharp tones and exchanges of internet voices. Goli hopes that each comment thread can itself become a small sub community of the larger community of This. He also hopes to create link rooms, where people who have all shared the same link can access the same digital space to discuss the article. The site also has pretty firm guidelines that are clear and enjoyable to read. “Don’t be an asshole” is one guideline. In reference to posting information about minors, the guidelines is “leave them alone.”

But if commenting is so problematic, why have comments at all? “Discussion is a vital part of democracy,” Golis argued. “Our culture is currently suffering from a breakdown of a lack of discussion.” And it’s true, any democracy benefits from the rigors of debate, from the college dorm room to the televised town hall.

An article for the BBC posits that our nostalgia for lost communities—including old-fashioned gossip and shit-talking—is what drives us to not only social media, but also to the comments section. “We have a vague sense of having lost something—the idea of chatting to a neighbour or meeting at the village post office,” Dave Harte, a lecturer in media communication at Birmingham City University, says in the piece. “In many ways, it is a media-created perception… But we are always trying to retrieve it and having a digital presence can often seem like a trouble-free replacement for meeting each other.”

So far commenters on This are taking it slow, like neighbors meeting for the first time. And most seem to be engaging with the piece, not by instigating personal attacks. “When you talk about online discussion, what you are really talking about is what kind of communities you want to make,” he said. “And if its a question of what kind of communities we are forming, then it’s a question of, well, everything.”

Golis admits that navigating This’s comments section will surely have its challenges. “But we are also so excited to figure out a way to do this,” he said, “because it is such a huge pain point for many people that they can’t have a decent and interesting conversation in any sort of public space on the internet.”