For all James Fosdike knows, the theft could have been going on for months. It wasn’t until an eagle-eyed Twitter user alerted the Australian illustrator did he find out that a replica of his artwork was available for purchase on an on-demand apparel website called Teespring. It was one, he’d eventually learn, of thousands of iterations of his designs being made into T-shirts and sold on the site by anonymous internet pirates.

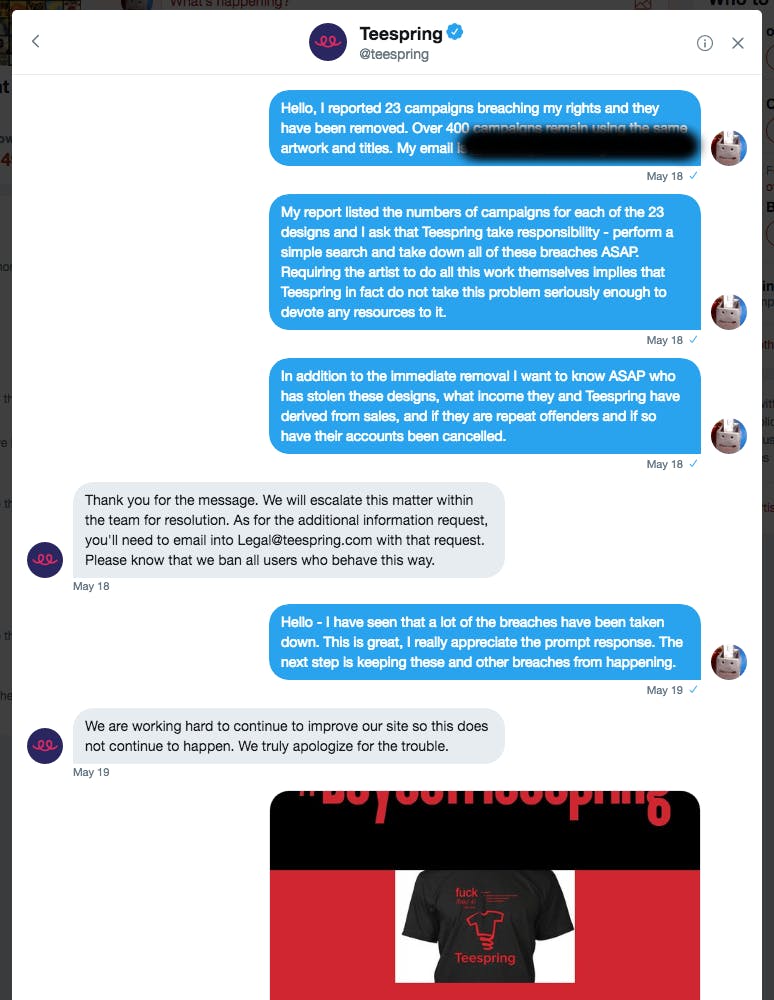

When he reached out to Teespring about the stolen work, he did what was asked by the company to prove the designs were his. The merchandise was eventually removed, but that process was only the beginning of an endless, time-consuming cycle. Ultimately, he found himself stuck in a game of copyright whack-a-mole.

“Every time I was getting stuff taken down … new ones would pop up,” he explains. “It would just be a case of [Teespring] replying to me saying, ‘We’ve taken down these,’ and I’d respond with, ‘Well here’s a bunch of new ones,’” a process he says made him feel as if he were trapped on a “depressing hamster wheel of gloom.”

Fosdike isn’t alone in his complaints. On Teespring, “creators” can launch campaigns for products to be sold for a limited time. The site then manufactures the design, with the proceeds going either into the wallet of the “person who created that design,” per the website, or to the creator’s designated charity.

But a number of independent artists who say they’ve found their work stolen and resold on Teespring haven’t seen any of those profits. They also have to continuously monitor whether others are stealing and selling their work, therefore losing money not only on potential sales, but also on the time they spend tracking stolen designs down. Because a pirated product often ends up looking shoddy and unprofessional—a pixelated and unfocused version of the original illustration—the artist’s reputation and credibility might also take a hit. The problem on Teespring is widespread enough, it has prompted the circulation of a Change.org petition, with over 2,000 supporters, demanding the company act on copyright infringement.

“I don’t want to say that the problem of an artist’s stolen work is bigger than anything else, because it’s [not],” Fosdike says, “but it’s my livelihood and I’m supporting a family with my artwork alone, so it’s a real pain in the ass to have to deal with this.”

Piracy is nothing new to creatives: Musicians have to worry about keeping their work off unauthorized YouTube channels; publishers need to police illegally uploaded PDFs; designers must make sure people aren’t pulling their logos and looks for illicit resale. Big brands may be able to keep teams on retainer to address copyright and trademark violations, but independent artists often can’t eat that cost. And while one might hope that the platforms where piracy happens would take responsibility for the theft they inadvertently facilitate, they often seem to hide behind copyright laws.

As part of its acceptable use policy, Teespring does mandate that creators aka “sellers”—not to be confused with “vendors,” according to a Teespring representative, as “’vendor’ falsely implies that we select our users and control and direct their activities”—use original work. Teespring also reserves the right to cancel a campaign or membership if a user “infringe[s] or violate[s] any intellectual property or other rights of others.” When asked if the company was aware of piracy taking place on its platform, a representative offered the following statement:

“Teespring confronts the same issues as countless other online platforms where the public can freely post content. Whenever rights-owners provide notice or we otherwise become aware of specific instances of user generated content that appears to infringe, we promptly take appropriate action.”

In response to a DM from Fosdike on Jan. 12, a company spokesperson told him: “Our team is taking IP issues very seriously and we are currently working on several initiatives to make reporting and prevention more effective going forward. We’re aiming to implement these initiatives early next week.”

That was Jan. 15, at which point Fosdike says just 200 of the over 2,000 examples of pirated work had been removed. While he waited on the company to get a handle on the situation, new products featuring his stolen designs popped up. Nearly six months later, Teespring says it did make an update in January but declined to say what that was, outside of the following:

“Teespring utilizes technology tools and internal processes to try to prevent users from uploading content that infringes [on] the rights of others. Among other things, Teespring provides convenient, user-friendly tools for rights-owners to utilize to notify Teespring of specific infringements by users, and Teespring promptly takes appropriate action and responds to rights-owner communications. Teespring’s technology tools and process remain confidential in order avoid alerting potential infringers of ways that may aid them in trying to evade our systems.”

And yet, the designers whose work gets stolen haven’t seen many changes in Teespring’s protocol.

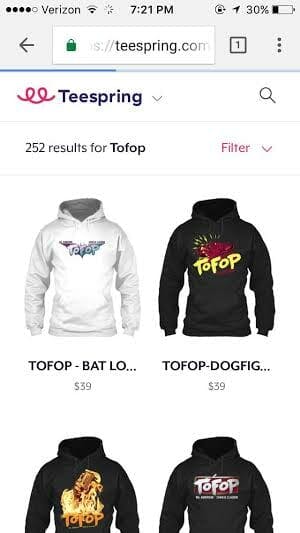

Chris Rees is another Australian designer locked in the Sisyphean cycle of fighting uphill to get one work removed, only to have a fresh avalanche of piracy tumble back down. Like Fosdike, Rees noticed that the problem sellers—whose names, unhelpfully, aren’t included on their Teespring pages—seem to rip his most popular designs off Redbubble, the platform where both artists authorize legitimate sales of their work. (Redbubble also advertises which of its vendors’ items sell the best, perhaps giving pirates an idea of what’s most profitable to steal.) And like Fosdike, he only discovered he was a theft victim when he heard about the Teespring problem on Twitter and decided to check it out.

He says he found other people selling around 30 of his designs on the platform, a total of about 270 campaigns, and set about the time-draining process of gathering press clippings and documentation of his work, all the information Teespring requested to prove he was the original artist and to meet the claim requirements of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). Teespring responded quickly, he says, and promptly took down the design. He followed up with an email linking to all the other examples of piracy he’d like removed, and a few days later, when Teespring said they’d taken down all the illegal copies, he assumed the matter was settled. That was in mid-May.

Fast-forward to June 10, when he took another spin through Teespring’s pages and found roughly 90 campaigns using his artwork. He notified the site again, and they responded two days later saying they’d scrubbed the pirated designs from the site. But almost immediately, he saw those products cropping up again.

Both Rees and Fosdike admitted that piracy of this flavor posed a problem on other retail sites, but said Teespring proved uniquely difficult to police. Teespring, Rees says, puts the onus on the victim to prove their work is their work, and to make sure the company stays on top of piracy.

“The nub of the problem is that [Teespring] has been getting feedback telling them what they need to do, and their response is ‘we’re working constantly to improve our processes,’ which is the kind of terminology you hear all the time from an airline that lets people down,” Rees says. “None of us have any idea [how to figure out] how many have been sold of our designs through this means, and therefore how much money that we have missed out on that we could feasibly have got if these buyers had come to our legitimate sites.”

According to Barry Heyman—founding and principal attorney at the New York-based Heyman Law who focuses on protecting intellectual property—piracy of this nature is widespread, and assigning blame is more difficult than one might expect. The DMCA, enacted in 1998, protects against copyright infringement online, but according to Heyman, often acts like an inadvertent shield for online service providers (OSPs) like YouTube, Google, or in this case, Teespring: If they can claim that they had no knowledge of piracy occurring on their platforms, if they aren’t earning money off of pirated works, and if they solicit user agreement to terms and conditions that prohibit users from uploading work to which they don’t have the rights, OSPs may not be legally liable for stolen content.

“They can’t monitor everything that gets uploaded to make sure that it’s original,” Heyman says of OSPs. “They have to have an agreement where the vendor or person that’s uploading it takes responsibility and says that it is original.”

If it’s not original, the person doing the uploading—in this case, the person who pulled a copyrighted image off of Redbubble and used it on Teespring—violates the law, even before money is exchanged. If an OSP receives a DMCA request to remove the material and they do, they’ve stayed within the law. But, Heyman continues, “There’s a tug of war there between [original authors] having to send take-down notices to YouTube or, in this case, to Teespring and constantly monitor this stuff.”

Where Teespring might find itself on shaky legal ground, however, is in the profit arena. How Teespring makes its money is the creator pays the company a flat-fee for the item they want printed, which is pro-rated depending on how much volume they sell, according to a Teespring representative. In turn, Teespring handles the manufacture of the goods, the sales platform, and the shipping. The creator makes money by selling the printed goods at a markup, keeping—or donating—whatever profit their “campaign” turns.

Unfortunately for Teespring, there does exist some recent legal precedent for copyright infringement: Greg Young Publishing v. Zazzle, a very similar lawsuit in which the court found Zazzle legally responsible for the copyright infringement taking place on its platform. Zazzle operates almost exactly the same way Teespring does, and because Zazzle (like Teespring) controls the manufacture of goods, it also profits from the sale of those goods. Because it benefited financially from copyright infringement, it was deemed liable for damages.

Still, Heyman cautions, “The knee-jerk reaction is to blame the platform,” and to a degree, it might deserve it. But the larger question, as he sees it, may lie with OSP protections. People want to hold someone accountable for theft: A platform that both enables users to pirate work anonymously and fails to police it should take some responsibility. But if court cases ramp up, what could be more likely—and more necessary—is a change to the law that was implemented at the dawn of the internet.