Twenty-five-year-old Peiying Feng spent most of her life split between living in China and living in Canada. To hear her tell it, the two are very different places when it comes to talking about sex.

“I remember two embarrassing sex-ed classes in Canada, and then it was back to China where there was nothing,” said Feng, who moved back to China at age 14 and attended college there before moving to New York for grad school.

“In college, there was a pamphlet shoved under the dorm room door with a bunch of food menus,” Feng said of her single encounter with Chinese sex ed. “If it’s not exam-related, they don’t teach it. And they screen sexual images out of movies.”

As a young woman who has observed firsthand disappointingly inadequate sex education in three different countries, Feng was on a mission: to create the first fun and popular game for teens that also happens to feature information about sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

As part of her final Master’s degree project at the Design and Technology program at Parsons, Feng designed Tap That: a mobile video game in which adorable characters fall for each other, make out, and expose each other to STIs in the process.

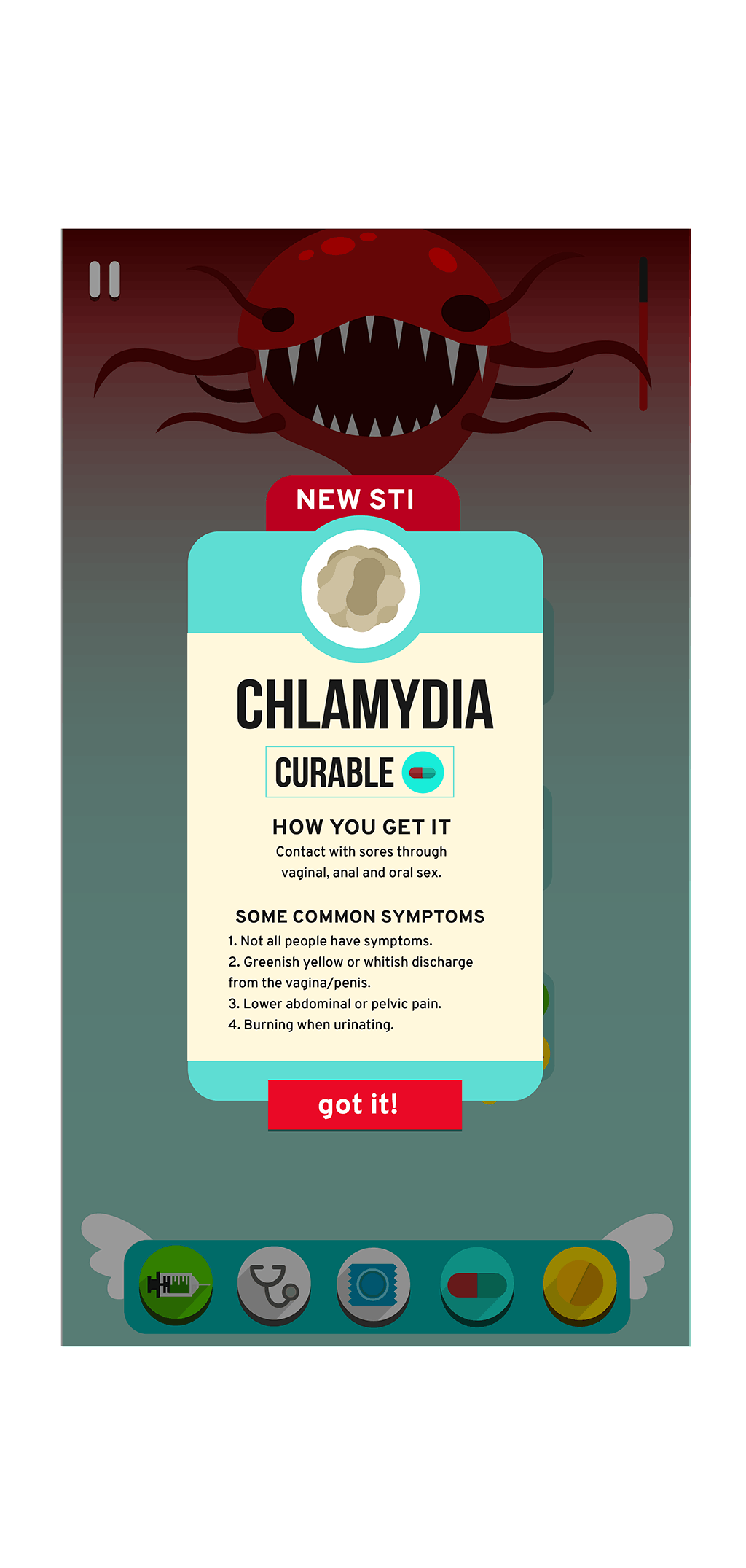

In Tap That, you never know when your characters will turn out to carry infections. One might turn green randomly, which means it’s sick. The game prompts users to diagnose from among nine different sexually transmitted infections (HPV; chlamydia; syphilis; hepatitis A, B, or C; herpes; gonorrhea; or HIV), which are either noted as “curable” or “treatable.” Then you choose between medication to cure it or treatment to manage it. If you get to it fast enough, a condom button helps protect the partner who is not sick from the partner who is sick.

Feng recently brought a beta version of Tap That to the Daily Dot offices for a few test plays (it does not yet have a release date). The game moves fast, but it’s addictive and stylish and it’s easy to forget you’re playing a game that’s essentially a sex-ed class. And that’s exactly what Feng wants; she knows her target audience has too much game-playing expertise to bother with something that’s not fun.

“I don’t even want teen players to think about the fact that it’s educational,” said Feng. “Unless it’s an excuse for your parents to let you play more games.”

Most STI-prevention apps focus on helping users locate testing facilities, like the government’s aids.gov locator. The most popular dating apps have recently added testing locator services, too: Tinder launched its partnership with Healthvana this January, following in the footsteps of the gay hookup app Scruff, which started running targeted STI-prevention ads in 2015. And recently, an Indigogo campaign was launched for Mately, an app that will allow Tinder matches to know who’s been tested for STDs and HIV.

There are also tons of apps for people living with STDs: from Aidsmap’s HIV drug glossary to dating apps like Hift and PositiveSingles that help people with herpes find understanding partners.

But there’s an enormous dearth of STD-prevention apps aimed at the one population that most needs sexual education: teens.

According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), youth ages 15–24 make up about half of the 20 million new STI cases that appear every year. One 2009 study found that four out of every 10 teenage girls ages 14–19 have a sexually transmitted disease like gonorrhea, chlamydia, herpes, or HPV.

The need for mobile technology to reach teens where they spend the majority of their time—on their phones—and teach STI prevention is indisputable. However, the first such game didn’t come about until 2014, when the Centers for Disease Control launched a development contest called Game On, offering a $30,000 total payout for the best STD-prevention games designed for mobile platforms.

One of the winners of the contest, STD Dodger—a retro-Atari throwback with falling STI modules—is currently in the App Store. In both STD Dodger and Tap That, the player can easily feel overwhelmed by the difficulty of avoiding what seems like a really nonstop onslaught of diseases. It may leave less sexually experienced teens wondering if sex is truly such a constant risk—and that’s exactly the point, because it is. The only way to win either game is to engage in protective activities (like condoms, testing, and treatment) that essentially buy time and a way to briefly avoid colliding with infections.

Feng is still working through the kinks, if you will, of her game’s rapid-fire hookups between horny characters who seem unaware of the monsters lurking at the edge of every hot date.

“I try to take people’s feedback and work it into the game,” Feng told the Daily Dot. She’s been able to test the game’s playability with her target audience via a Parsons partnership program with local middle schools and high schools that brought teens into the classroom to check out the design students’ various mobile apps.

“My target audience is 13–15 year olds, right before they start having sex,” said Feng. “The teens younger than 13 didn’t really have an understanding of what sex was. The 17-year-olds already had some knowledge of what the subjects were, and they were able to play and just have fun.”

“I had one girl who kept playing over and over,” Feng recalled. “They all thought it was a better than a sex-ed class, which I agree with.”

Feng’s background, in and of itself, is a clear example of why games like Tap That are so direly needed. She recalled the absurdity of Chinese approaches to sex education (which is virtually none) in a conservative culture that relies heavily on abortion. Due to the one-child rule, said Feng, abortion is “widely available and encouraged,” but there is zero information about sexually transmitted infections. As a result, Feng watched as her high school classmates engaged in rampant sexual activity without any awareness of STIs or even how pregnancy occurs.

“A lot of teens are having sex, but they are learning everything from porn sites,” Feng told the Daily Dot. “I knew girls who were like 14 or 15 and already having sex. You don’t teach them about STDs or contraception, so they don’t even know if they have STDs.”

Feng said that in China “girls are raised to be really obedient” and frequently don’t say anything if their boyfriends refuse to use condoms. “I had friends who would ask the weirdest questions about sex—like, ‘If I kiss a guy, will I get pregnant?’”

Unfortunately, sexual education isn’t widely accessible in America, either. According to a March 2016 overview of state-by-state sex-ed policies published by the Guttmacher Institute, less than half of U.S. states mandate that sex education be taught. Ironically, while only 24 states mandate some form of sex education in schools, 36 states and the District of Columbia mandate that parents be allowed to remove their children from sex education classes if they are taught, and 26 states require that abstinence be stressed. The overarching state of sex education in the U.S. is one in which youth are supposed to be taught not to have sex at all, and parents are encouraged to shield their children from learning about sex, period.

“I was really surprised,” said Feng. “The states has this reputation of being more sexually open than the East. All this talk of abortion and abstinence-only education and stuff—it doesn’t make sense to me that people are so critical of sex. Teens are not going to just stop having sex because you tell them to.”

Ideally, Tap That could be a series along the lines of the Angry Birds franchise but for real-life sexual complications and conundrums; each installment could expose the game’s sex-loving couples to different challenges, such as unintended pregnancy or problems with consent. But for Feng and all other game developers seeking to educate the teen population about sex or anything else, the final crucible is that the game be fun to play.

“After all, sex is supposed to be a positive experience,” wrote Feng in a paper explaining her game. “So why shouldn’t sex education be as well?”