My question upon entering Space Jam, a solo gallery exhibition by Devin Troy Strother that draws inspiration from the highest-grossing basketball movie in history, was childish, almost petulant: Where are the Looney Tunes characters, I wondered—is this guy afraid to get sued?

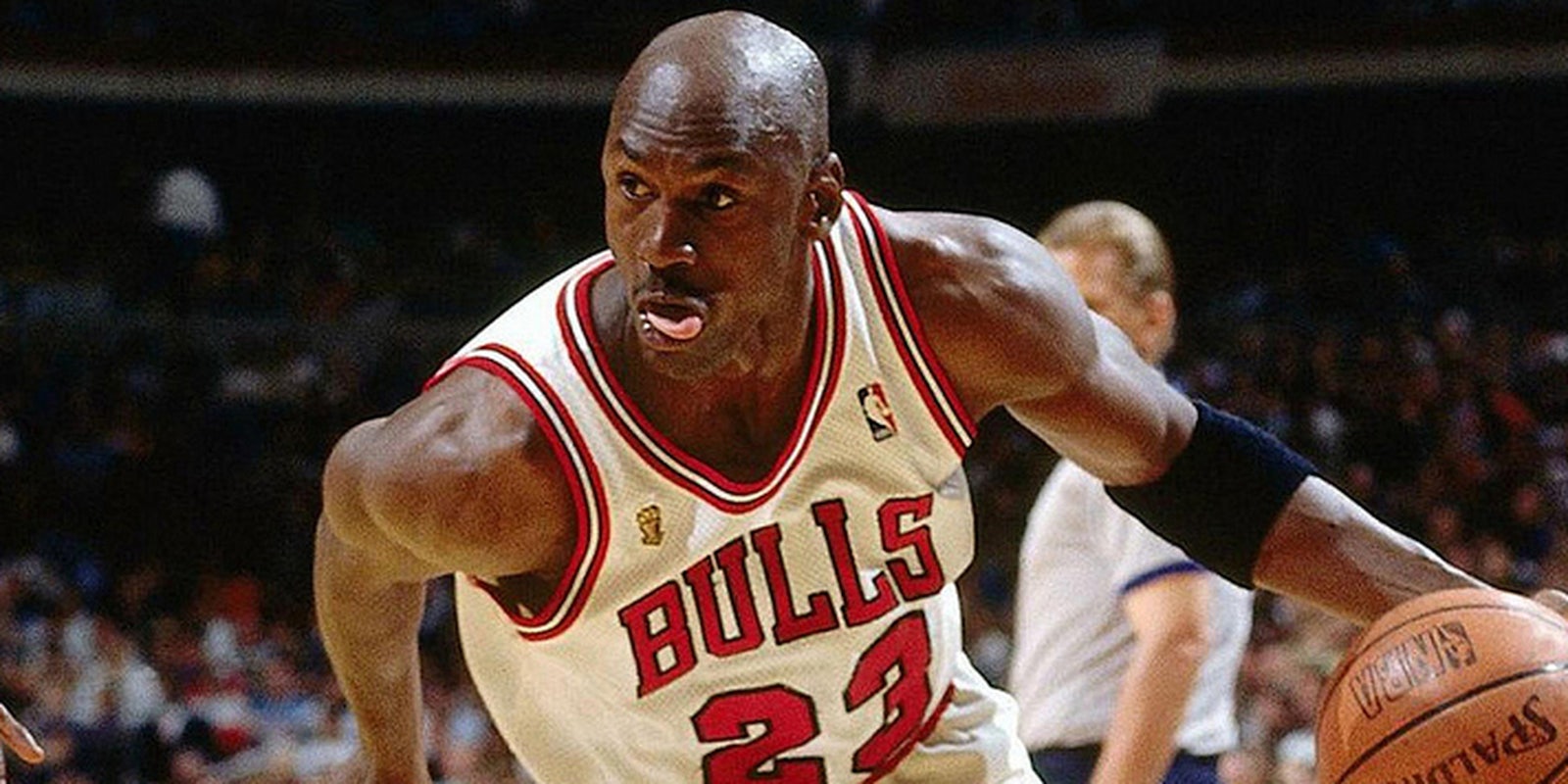

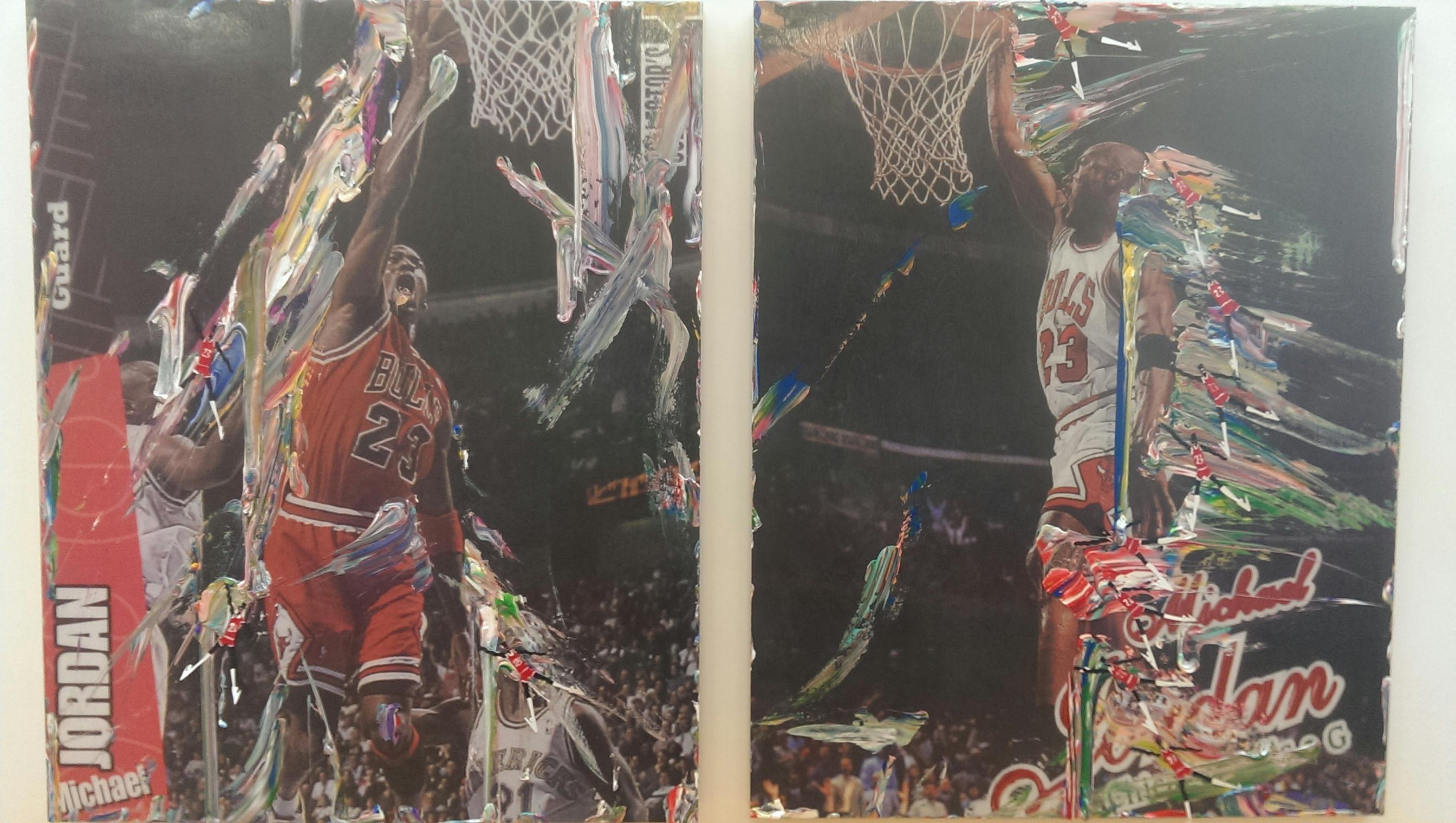

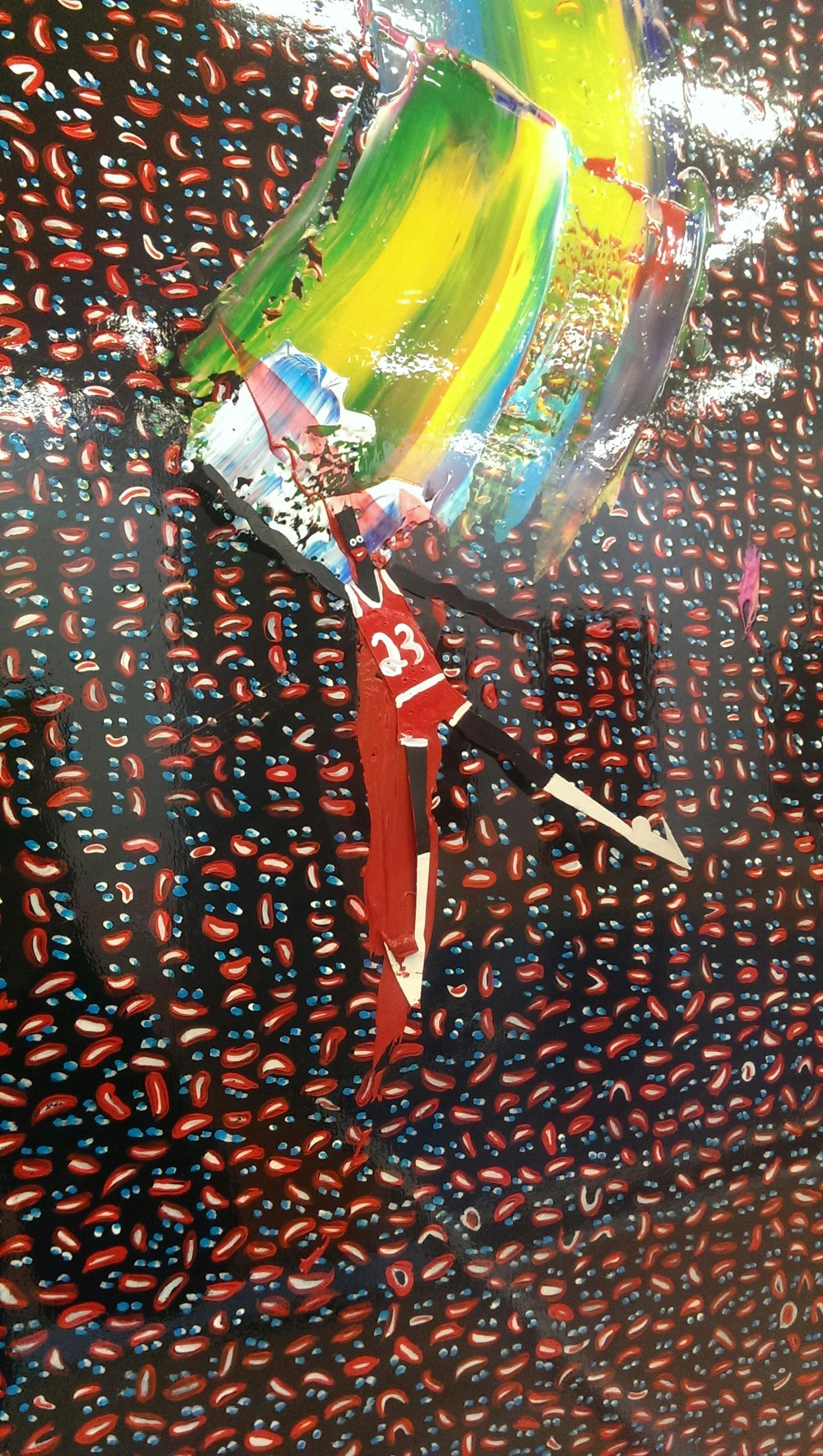

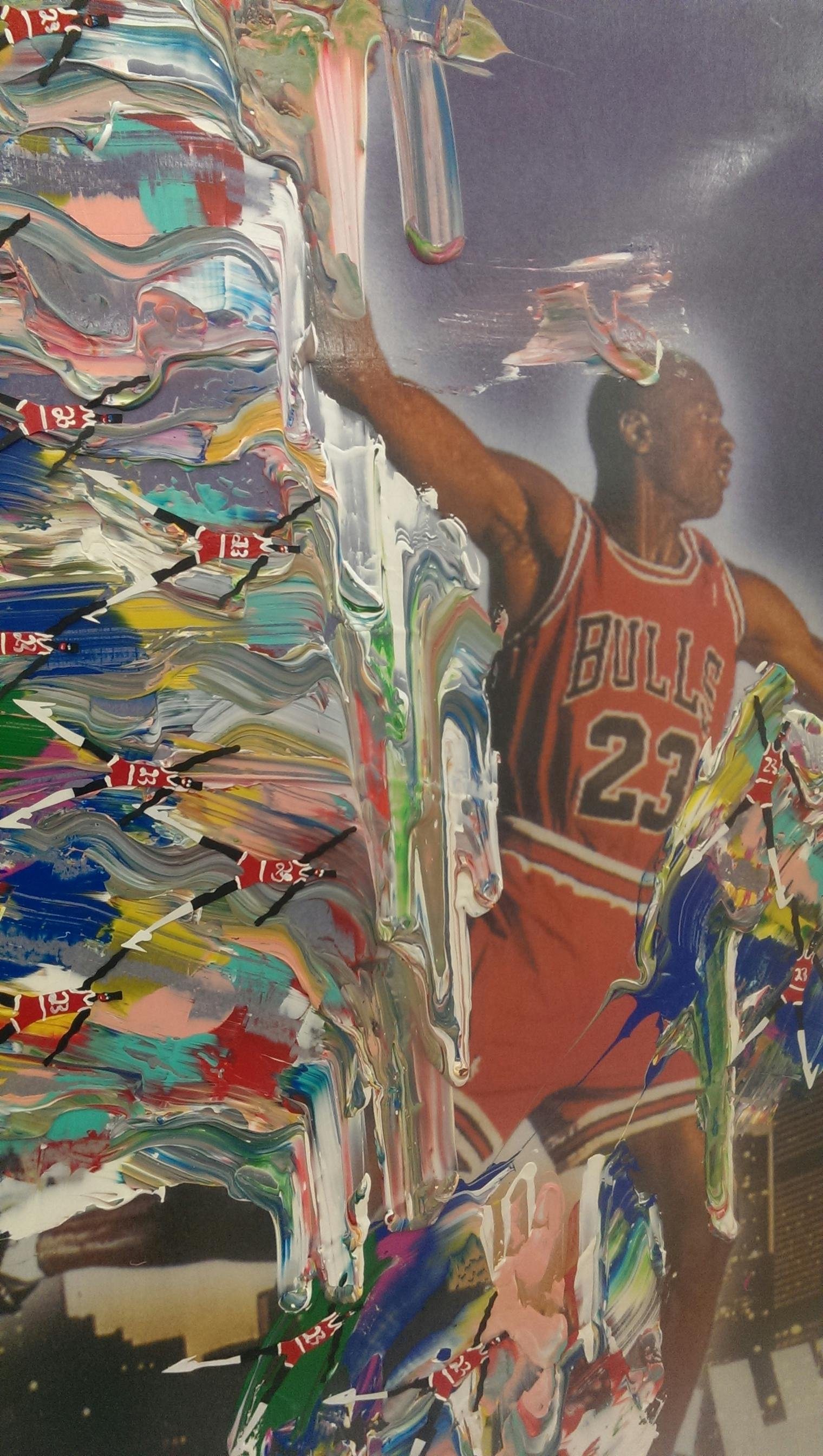

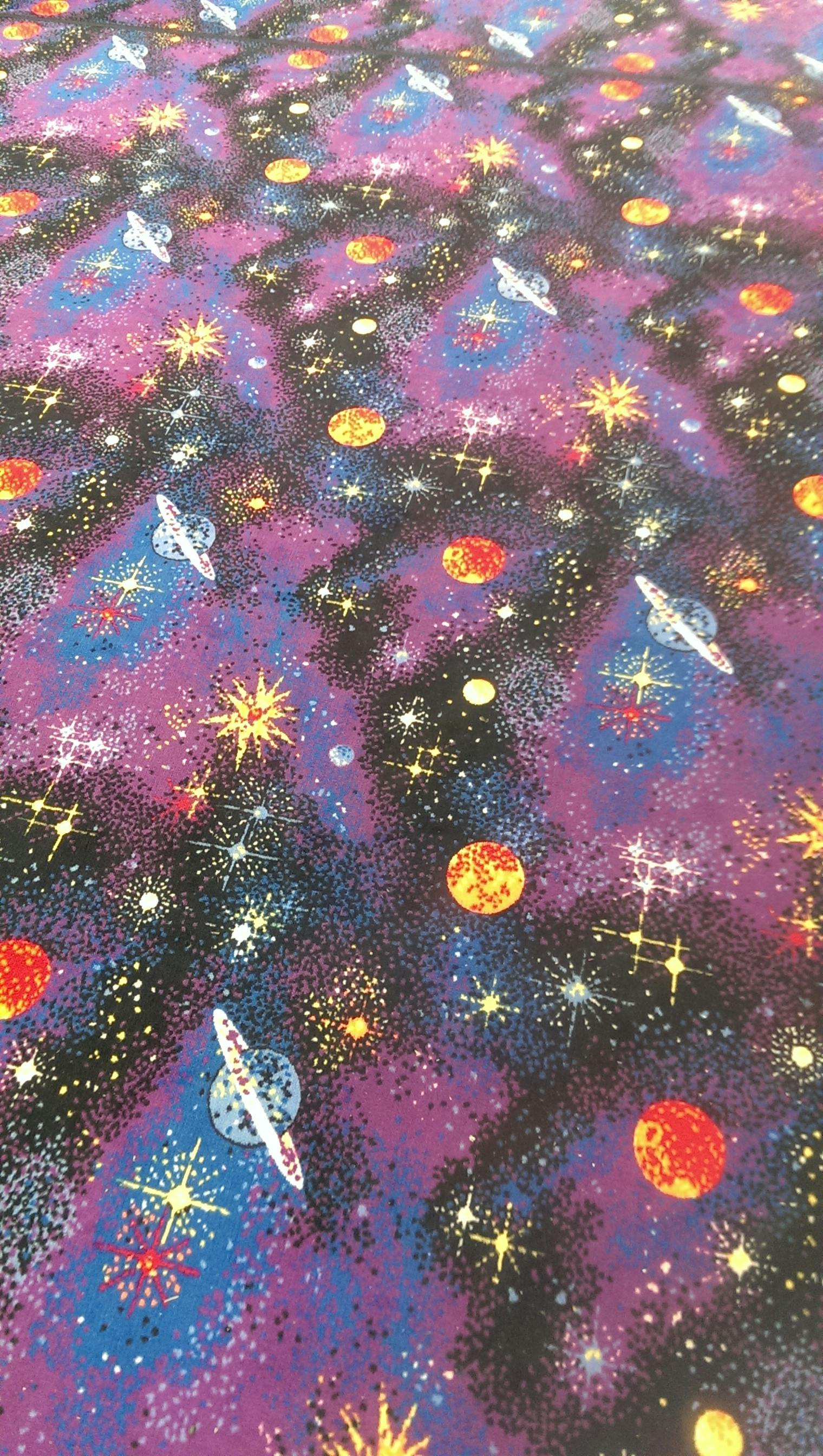

But visit the show for yourself—through Feb. 14 at New York’s Marlborough Chelsea—and the tenuous link to its avowed source material becomes a concern wholly subordinate to body and hue, surface and reflection, drive and defeat. As with the watershed film, Michael Jordan is the true star, and Strother depicts his athletic prowess (at its height) as the sort of thing that can plausibly shred the fabric of our reality. It opens rifts into dimensions of pure artifice. His gestures emerge and cohere from cacophony of color: it’s Jordan as cartoon, not in one.

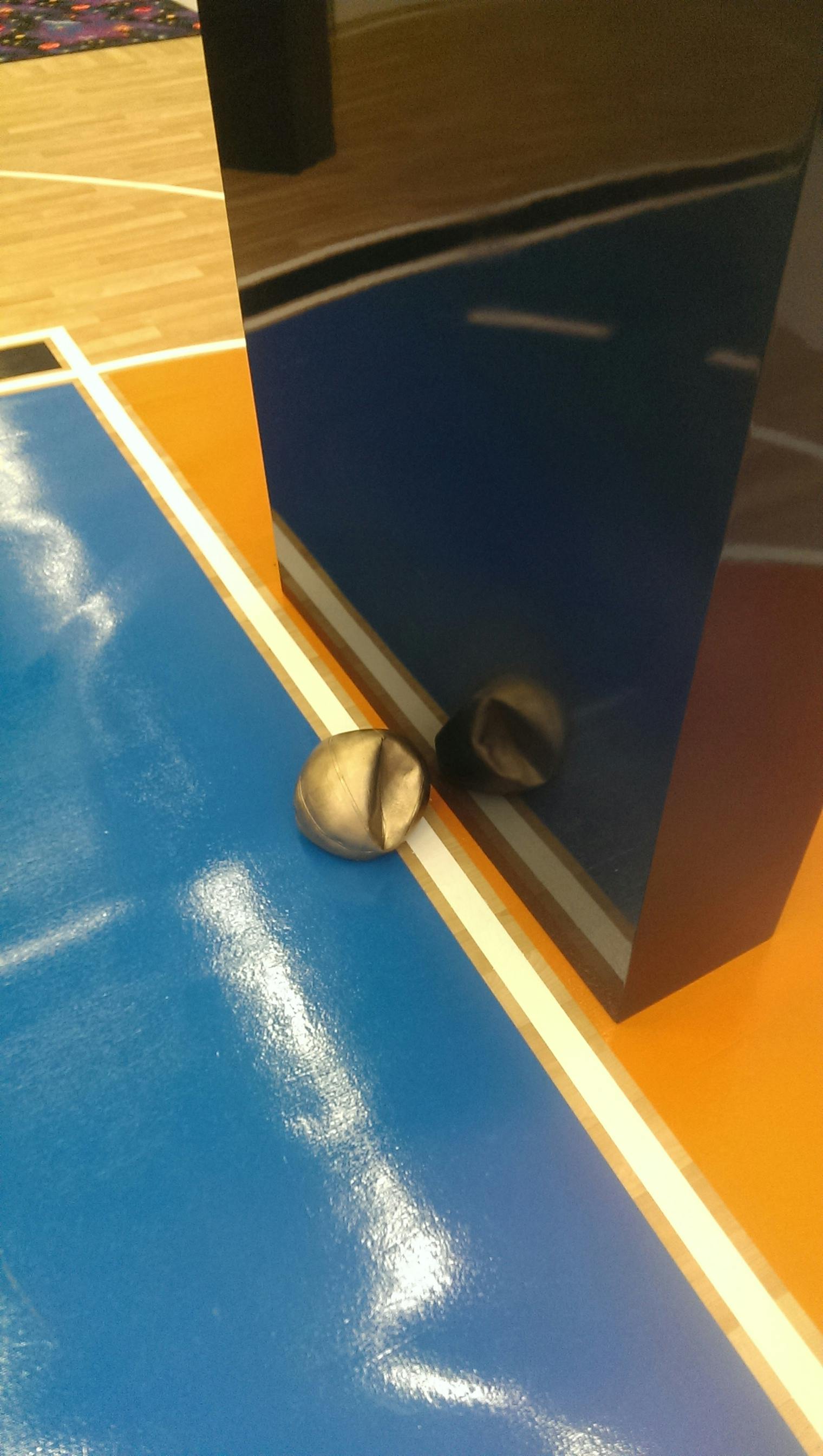

This is how we view professional sports: a collection of physically improbable persons achieving physically impossible ends. Not for nothing does the movie depict Jordan’s arms stretching like taffy for a half-court dunk. The best alley-oops enact the same balletic absurdity of the finest Bugs Bunny prank. And Strother’s truncated court, the fixed plane against which kinetic beauty is staged, reminds us of the cheap, static, and endlessly recycled backgrounds in a Road Runner chase sequence. Then there are the punctured gold basketballs, heavy black monoliths, and marble backboards, items that marry visions of glory to solid limits. Space Jam, it’s worth remembering, was a revisionist history of Jordan’s disastrous and short-lived pro baseball career, that odd interregnum between his glorious NBA regimes.

The exhibit loses focus when given over to mere collage and by-the-numbers abstraction, though it retains, in tangled pennants and gratuitous glitter and chunky paint, the fiendish inertia of an animated world. Race looms over much of the work as well—Jordan is sometimes given a face out of the minstrel tradition, one that patterns across a few canvases, though Strother has said in an interview that his exaggerated red-white-and-blue features have more to do with being an American than African-American. Really, what’s more American than leading the U.S. “Dream Team” to Olympic glory in 1992 only to later say that you would rather have gone golfing and sure as hell won’t be playing in the 1996 games?

Lurking beneath all is the specter of commercialism. Strother’s supersaturated tones are as loud and attention-snaring as a highway billboard or subway poster (or NBA franchise uniform). Space Jam was derided by many critics as a well-calculated though underwritten cash grab, an extended Nike ad that leveraged the return of basketball’s prodigal son to resurrect long-dormant Warner Bros. intellectual property. That it mocked Disney with a failing amusement park called Moron Mountain doesn’t excuse its craven need for blockbuster status, more than confirmed by rumors of a LeBron James–starring sequel. You could attack Strother’s more slapdash pieces, too, as low-stakes, high-profit eye candy, but they’re imbued with the same earnest charms that make their namesake feel less cynical than silly.

Neither Space Jam has a message, per se. If they ring hollow, it’s because they principally exist as exercises in style and form, alchemic brews with more than a passing resemblance to confusing, overcrowded dreams. But both posit that delusions of greatness—again, consider Jordan’s move to baseball—are nearly as potent as victory itself. As R. Kelly sang: “I believe I can fly/I believe I can touch the sky.” Maybe believing is enough.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIQn8pab8Vc

Photo by Jason H. Smith/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)