SARK is weird. That was my first impression upon receiving her nearly 20-year-old book, Succulent Wild Woman, a few Christmases ago. It was colorful and slightly goofy and used words like “succulent” sincerely. There were tips on how to start journaling, and little sketches of hearts and stars all over the place. But SARK, aka Susan Ariel Rainbow Kennedy, is no joke.

Over the span of nearly 30 years, Kennedy has created an empire. It began with books and posters, and has expanded onto the internet, where she holds video classes and conferences, posts inspirational memes, sends a weekly newsletter, and has hundreds of thousands of people following her every word about life, love, and being a woman. And, according to her, the internet is allowing for emotional vulnerability on a scale we’ve never seen.

SARK, the name, was born in 1982, when Kennedy began selling artwork and posters under that moniker. In 1991, she published her first book, A Creative Companion, as part of a brand to encourage self-discovery and self-acceptance. The book was about “how to free your creative spirit,” a half-self-help-guide, half-journal, full of creative activities and exercises. “Try: studying something in nature for one hour or longer: snails, ants, butterflies, leaves,” she writes, and reminds readers “your desire to feel creatively free is very important.” The book is splattered with rainbow watercolors of flowers and people and shapes, the kind of things you’d finger paint, if you had finger paint and nobody was looking.

All of it looks a little woo-woo on the surface. When I first received Succulent Wild Woman, I figured it was just another New Age-y self-help book that might be good for a laugh. According to Kennedy, that’s the impression a lot of people get.

“I think SARK gets mistaken for being mindlessly positive, and that was never the case,” she told the Daily Dot. “Usually, if someone is saying that, I ask if they’ve read a SARK book, and they confess they haven’t.”

When I finally did crack open the book, what I found were beautiful descriptions of how to find love and acceptance juxtaposed with some extremely serious subjects. SARK writes about the many hardships she’s gone through—eating disorders, depression, and being sexually abused by her brother at a young age.

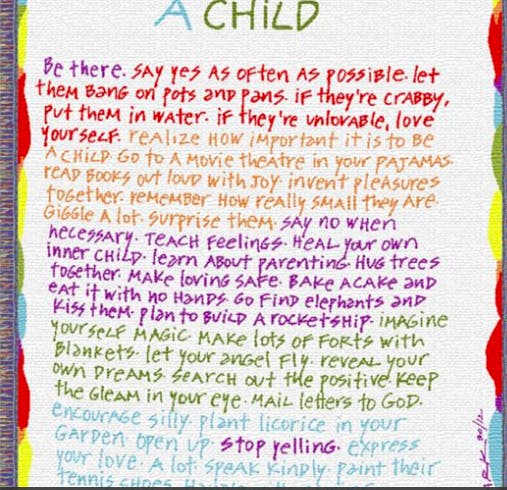

In one section called “How to Forgive Your Father,” she spoke to their disappointments with each other. “I wanted a daughter who would wear an apron and make soup from a ham bone,” he said of her. Through the page, she reveals sadness and love and acceptance. “She feels the love and forgives the pain.” It’s stuff that, I thought, shouldn’t be handwritten next to drawings of hearts and stars.

But for Kennedy, that’s exactly the point. “I insisted on bright colors because, initially, someone could think it’s one thing, but it gets them to go deep without realizing what they’re doing. I like that. I never wanted to approach it like, ‘Here is a tough book about incest and depression and suicide and sadness, and you will learn how to live with these things.’”

That mixture is exactly what drew Ben Yakas, the friend of mine who bought me Kennedy’s book, into her world. “SARK became this joke for a while, especially once I was signed up to her newsletter,” he said. “But something changed over time. I don’t know if SARK wore me down with her sincerity, but I started to find Planet SARK to be more charming than worthy of ridicule or anything like that. What started out as a joke between friends became this strange, sweet presence in my email box unlike any other newsletter I received.”

In many ways, Kennedy’s work is the precursor to the vulnerable, confessional writing we see across the internet, especially from women—which comes with risks. In an essay for Slate, Laura Bennett warns of the dangers of “The First Person Industrial Complex,” which she argues mines women writers for their most personal details at their own peril. “On its face, the personal-essay economy prizes inclusivity and openness; it often privileges the kinds of voices that don’t get mainstream attention. But it can be a dangerous force for the people who participate in it,” she writes. Writer Haley Mlotek argued against Bennett’s point at The Hairpin, saying, “This kind of hand-wringing amounts to the cheapest, most abundant, and most widely-traded commodity in this industry: the business of telling women it would be better to just not write.”

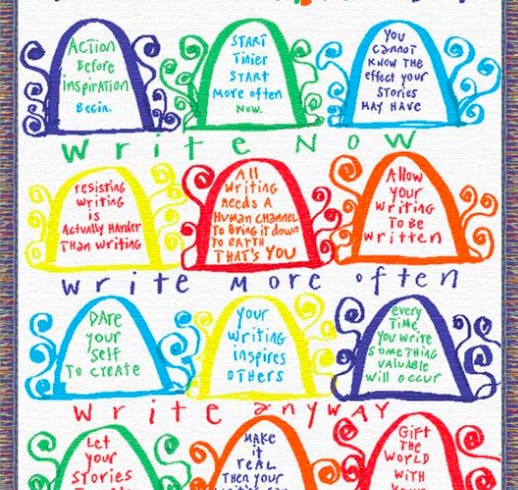

Kennedy understands that writing about such personal issues is scary, and can invite criticism and harassment, but the SARK brand is all about the rewards one gets from taking that risk. “The only way we get unstuck is by naming things, bringing them to light. Isn’t it wonderful how so many things are coming to light?”

On March 6, Kennedy sent an email to newsletter followers saying her fiancé and collaborator, Dr. John Waddell, had died of cancer after being diagnosed just nine months prior. “I am doing well, interspersed with terrifying waves of grief and immense relief that we’re both free from the physical care and emotional space holding that all of this required,” she wrote. “I am allowing all my feelings to be present in my emotional family.” The email was sad and raw and sweet, all at the same time. And for SARK, that’s exactly the kind of emotional complexity the internet fosters.

“I felt like I was waiting all my life for the internet to catch up with me,” Kennedy told the Daily Dot over the phone. “People talk about past lives, but I have future lives. And I have memories of all this incredible technology I used in the future, and I couldn’t believe how archaic it was here.”

In 1998, she started her first website, CampSARK.com, which sold her books and artwork, but also had the Marvelous Messageboard, where users could discuss her teachings, artwork, or anything else they wanted. It was there she started to find a dedicated audience. “People who were on that messageboard in 1998 are now in my Facebook group,” she said.

In the late 2000s, she launched PlanetSARK.com, which is now the core of her business. She has over 140k Facebook followers, 14k Twitter followers, and has sold approximately 2 million books. “I think the internet, everything connected with the internet is miraculous,” she said, noting how Facebook and video conferencing had exploded since her first foray online.

In some ways, it’s incredibly easy to be honest on the internet. People can share every thought on Facebook and Twitter, every selfie on Instagram, and many have used those platforms to explore more radical forms of honesty. The Daily Dot’s Selena Larson recently wrote about how posting selfies helped in her recovery from an eating disorder, and other writers have explored the pros and cons of posting about depression and mental health issues on social media. But what Kennedy hopes to discourage is what she calls “impression management.”

“Our joy and our sadness are together like bird wings. They operate in concert,” she says, and when we use social media to post about just one or the other—only posts about how sad we are, or only posts about what a great time we’re having—nobody gains anything. “People don’t understand how much more emotionally intimate they can be if they share things that are in the fullness of experience.”

Which is hard to do, because everything on social media is, on some level, a performance. People choose what to say and when to say it, to use a filter or not, to open up about struggles in ways that are still protective. They tailor their language depending on if their moms are reading, and tend to save the more brutal honesties for conversations IRL.

But Kennedy leads by example, being forthcoming about the good and the bad, whenever makes sense to do so, and hoping others learn it’s OK to do the same.

Quoting Katherine Hepburn, Kennedy says in one video, “I’m afraid all the time, I just act as if I’m not.” She speaks of fear in the first-person plural, but you can tell she is speaking about herself. When she talks of fear being the voice in your head, saying, “you’re not writing, you’re failing,” you understand it’s something she’s personally felt. She acknowledges negative feelings, yet manages not to dwell on them. She’s afraid, but she isn’t defined by fear.

SARK transcends the internet’s tone problem. What can sound serious face-to-face sounds REALLY serious online, and what may be funny in person can sound glib in a tweet—but she makes those two sides work in concert. And while the internet is also slowly learning of the power of sincerity—as opposed to irony—Kennedy already has that down in spades.

“I will start a call and say, ‘I’m crabby and shy, and why I was thinking this was a good idea,’” she says. “‘And if anyone else feels introverted and shy raise their hand.’ And I’ll say, ‘Let’s welcome the introverts, welcome our shy parts, allow that everyone is where they are right now and that’s exactly where they need to be.’”

Kennedy knows exactly where she needs to be. And maybe, eventually, the internet will catch up with her.