Opinion

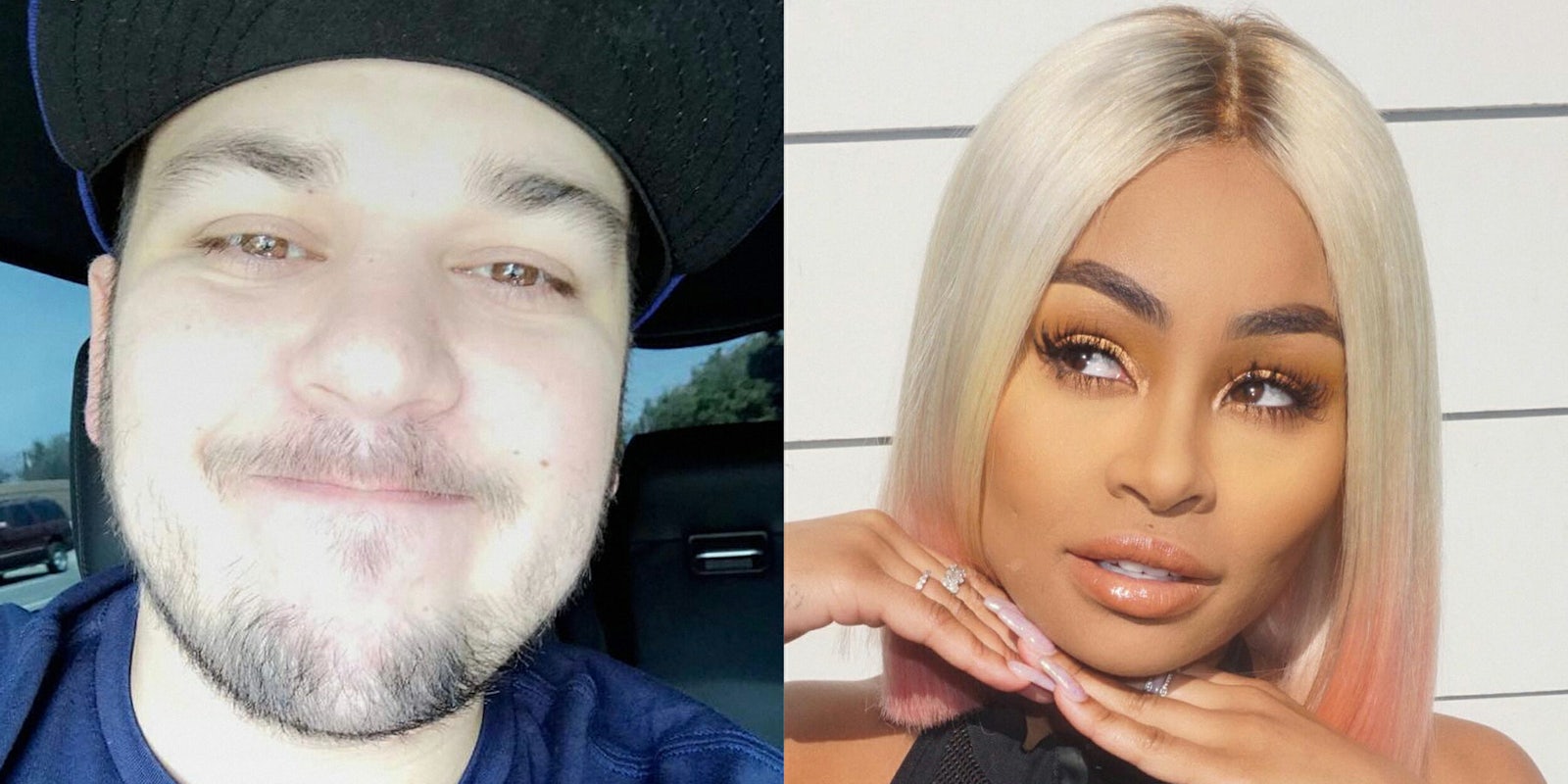

America’s most inescapable reality show dynasty knows how to make headlines, but unfortunately for Rob Kardashian, potentially committing a sex crime is the wrong kind.

The 30-year-old sock designer and brother to Kim, Kourtney, Khloe, Kendall, and Kylie was temporarily banned from Instagram on Wednesday after he began sharing sexually explicit photos of Blac Chyna, his ex-fiancé. In a series of posts, which he then took to Twitter, he accused Chyna of being unfaithful. “But she couldn’t remain loyal and cheated and f**ked way too many people and she got caught and now this is all happening and it’s sad,” Kardashian said of the model and entrepreneur.

https://twitter.com/robkardashian/status/882684690221674496

While the former couple, who share a child together, documented their tumultuous relationship on the E! reality show Rob & Chyna, what transpired on Wednesday crosses a clear line: Sharing nude photos of someone without their consent, especially to enact vengeance on a former lover, is a crime. Often known as “revenge porn,” it’s illegal in 38 states and the District of Columbia. In Illinois, Kardashian’s actions could constitute a felony.

But revenge porn is still a relatively new, and thus complicated, subject in the eyes of the law. New Zealand’s Joshua Ashby has the dubious distinction of being the first person to serve jail time for posting an ex’s nudes on Facebook. In 2010, he spent months in prison under the country’s morality and decency codes, because the Kiwi government didn’t have laws specifically prohibiting revenge porn. Like many countries, it still doesn’t. Although Germany and the United Kingdom have taken steps to end the practice, the United States still lacks federal legislation banning nonconsensual pornography.

That could be because internet law is still not-well-treaded territory, but it could also be because, like most hard-to-prosecute crimes, the victims are women.

Let’s take a brief look at the data on revenge porn, which is more widespread than you might think. A survey from the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI) found that 90 percent of those who had their private photos and videos distributed were women. The survey doesn’t provide hard data on the overall number of victims, but we can extrapolate: The Atlantic reports that around 10 percent of all people claim that a former partner has harassed them by threatening to leak their most guarded, intimate moments to the public, and around 60 percent of assailants will make good on those threats.

If those numbers are accurate, that means more than 1.7 million of the estimated 125.9 million adult women in the U.S. have been victims of revenge porn.

At least anecdotally, the disproportionate impact of revenge porn on women is obvious. The vast majority of the celebrities targeted in the 2014 nude photo leak on 4chan (pejoratively dubbed “The Fappening”) were female. They included Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Upton, and Ariana Grande. Actress Mischa Barton, the former teen soap star who appeared on The O.C., won a lawsuit filed earlier this year against ex-boyfriend Jon Zacharias. Barton claimed in court that he filmed her without her consent and then began to shop the recording to porn outlets as a “sex tape.”

The public ordeal of being a revenge porn survivor also often has long-term consequences. In addition to experiencing job loss and public shame, the CRRI found that nearly half of victims considered taking their own life as a result. A staggering 93 percent suffered severe anxiety and depression during the aftermath.

Imagine how it must have felt for Leah Juliett, a 14-year-old student who had private photos of her distributed to every guy in her high school. Her male classmates might not have known her name, but they knew what she looked like naked. There’s also Nikki Rettelle, whose ex-boyfriend planted hidden cameras in her home to record her every move. Rettelle told CNN that the man, who she mockingly calls “Mr. Wonderful,” sold the footage to websites like IsAnyoneUp and UGotPosted. The latter was run by Kevin Bollaert, who received an 18-month prison sentence in 2015. He also operated a site where you could pay $350 to remove the same photos he posted.

The laws that protect these women vary by state, and they often aren’t enough. What constitutes consent in one locality could be very different from another.

One major issue is the conundrum of having “evidence” that will satisfy potential prejudices of a judge and jury. TMZ speculated that should Blac Chyna decide to pursue her case, it could be a challenge: She “liked” Kardashian’s post prior to its removal. That may assist a defense team in proving that the 29-year-old wasn’t harmed by the content being shared—never mind that he it seems clear, by his messaging, that he did so without her consent.

https://twitter.com/robkardashian/status/882690256918781952

Then there are the nearly dozen states that lack any laws on the books criminalizing revenge porn. These include Kentucky, Mississippi, Ohio, and Wyoming, in which Blac Chyna would have no legal recourse for seeking retribution at all. Jeff Metzmeier, who works as an attorney in Louisville, Kentucky, told the city’s Courier Journal that he sees a “dozen” cases every year where the victims simply have no options. Metzmeier said that many are domestic violence survivors who have recently left their abusers; their exes use the threat of sending private photos to shame them into remaining in a toxic, violent relationship.

There has been a push in recent years, however, to strengthen the laws around revenge porn through federal legislation; these bills are designed to help a government that remains light years behind on cybercrime better advocate for victims.

The Online Safety Modernization Act, introduced to Congress in June, would target harassment in digital spaces—whether through doxxing, sexual extortion, or sharing nonconsensual pornography. Since 2015, U.S. Representative Jackie Speier has been pushing her own legislation, called the Privacy Protection Act, and a bill making revenge porn a crime for members of the military passed the House of Representatives earlier this year. Called the Protecting the Rights of Individuals Against Technological Exploitation (PRIVATE) Act, the bill would update the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

While Congress debates the issue, certain states have stepped up their fight against sex crime in digital spaces. California, where Chyna calls home, launched a dedicated eCrime unit in 2011.

But more must be done—not only to allow victims to seek justice but to educate the public on the damage revenge porn does. Although media coverage has correctly labeled Kardashian’s actions for what they are (e.g., potentially illegal), social media has treated the controversy like just another reality show spectacle. Twitter users have posted GIFs of Michael Jackson eating popcorn, the time-tested expression of a platform waiting for more juicy drama. What happened to Chyna, though, isn’t entertainment. It’s yet another example of abusive men using social media to shame women into submission.

If Chyna decides to press charges, she will have the ability to have her day in court. But we must fight for a world where all victims have the same opportunity.