Ross Hammond hadn’t received a message in weeks.

A 30-year-old gay man who lives in New York, he keeps a folder filled with various dating apps on his phone—including Grindr, Scruff, and Tinder. Since moving to Hell’s Kitchen two months ago, he says he can “count on one hand” the number of messages he’s gotten from men in the popular Manhattan gayborhood.

Hammond, a bearded aspiring musician with an endearing nervous energy, decides to engage in a little experiment over coffee in a Harlem café: He changes his profile picture to a male friend’s photo. The friend is cute and clean-cut, but most importantly, he’s white. Hammond gets 50 messages in less than a half hour.

Hammond isn’t surprised. He’s pretty used to this. His current profile, in which users are asked to describe themselves, attests to the frustration he experiences as a gay man of color navigating the world of online dating. “It doesn’t matter what I write in my profile,” Hammond says. “You’re not going to read it because you’re automatically going to make assumptions about me based on my race.”

Recently, someone sent Hammond a message that has stuck with him. “You fucking chinks are the reason why there’s so much racism in the gay community,” it read.

Hammond’s experience is a sadly common one in online dating spaces. Christian Rudder, the founder of OkCupid, told NPR back in 2014 that there’s a “bias” across platforms against black and Asian users. “Every kind of way you can measure their success on a site—how people rate them, how often they reply to their messages, how many messages they get—that’s all reduced,” he claimed at the time. A year after Rudder’s comments, researchers in Australia polled 2,000 gay and bisexual men, finding that 70 percent felt that excluding a sexual partner based on their ethnicity wasn’t racist. These respondents believed that having disclaimers on your profile like “No Blacks, No Asians” was just stating a preference.

The topic of sexual racism has become a contentious one in the gay community in recent years, as many queer and bisexual men rely on their phones in the way they once did their local bar. And if these spaces are operating as the new gay club, that leaves certain types of people in these online communities out in the cold, waiting for their chance to finally be let in.

As gay men of color explain, it’s can be difficult to find your place in a community where you’re too often shut out by people who believe that exclusion is harmless—and even natural.

The perils of the profile pic

To hear Cesar Bojorquez and Evan Adams’ stories side by side, it’s startling that they have so much in common. Although users frequently use hookup apps to meet guys searching for some after-work delight, both of them first logged on looking for friends.

Newly out of the closet, Bojorquez and Adams knew that signing up for apps like Jack’d and Growlr was how you meet people, especially when you aren’t old enough to go to the bar. When they didn’t receive any replies from other users, neither of them felt that this was unusual. Adams, who is black, thought it was “normal” to be signed in for weeks at a time and not get a message.

“It took a toll on my self-esteem,” Adams says. “I wondered, ‘Why not me?’”

“I thought that was the culture,” Bojorquez adds. “But when I talked to my white friends about it, it was if they lived in a completely different world. Their profiles are flooded with hundreds of different messages and filled with conversations with all different kinds of people. My friends of color, though, had the same experience as me: You rarely get a message and rarely does someone respond to yours.”

Bojorquez, who says that he gets “very few” messages on dating platforms, claims that it “took a little while” to understand why people weren’t responding to him. A 28-year-old makeup artist, Bojorquez is not only Latino but effeminate. A self-described “casual punk,” he performs drag in Salt Lake City, the heart of Mormon country. His profile photo on Facebook is a picture of him in a red wig that’s like The Little Mermaid’s Ariel meets seapunk—complete with a metal bridge piercing right between his eyes. He knows that his brand of fabulousness isn’t what a lot of guys are looking for, but Bojorquez had to learn that lesson the hard way.

At first, Bojorquez didn’t have a photo of himself on his profile. He found he got more responses when he left his photo blank. One day Bojorquez was chatting up a cute guy who also liked Star Trek, and they talked about what they’d been watching on Netflix. They were really hitting it off—that is, until the man asked for a face pic. Bojorquez sent over a picture of himself hanging out with friends at a party—a white infinity scarf pulled over his neck to protect from the winter cold and hair up in a topknot. His conversation partner was no longer interested.

“The fact that I was Latino just changed his mind completely,” says Bojorquez. He adds that he’s even been called a “wetback” and an “illegal immigrant” by guys online.

“Sometimes I wonder if I’m doing this right,” claims Adams, a 24-year-old art director who lives in Los Angeles. “I see my friends who are always with new people or going on dates. It makes me feel left out and isolated knowing that it’s not as easy for me to navigate the gay scene. I’ve struggled with not feeling attractive enough because there are such strict beauty standards in the gay community around what’s considered attractive. You have to fit into that box.”

The biases we’ll reveal in private

For gay men who were the first generation to grow up with a home computer, applications like Grindr and Scruff are an outgrowth of an earlier technology: the chatroom. Services like AOL, as well queer-specific platforms like Gay.com and XY, were like stepping into a cocktail party that was already happening. By joining in the conversation the room was having, users could identify guys they might like to get to know a little better and pair off.

However, today’s gay digital spaces eliminate the communal in favor of a more personal form of conversation. Platforms like Grindr and Scruff are commonly known as geosocial networking apps. By scrolling through a grid of available men in your area, guys who use the app can select profiles that interest them and message them directly. In order to match users with others who share their interests—sexual or otherwise—these applications pinpoint your location to show you other users who are nearby.

Grindr, which launched in 2009, was the first peer-to-peer app for gay men to achieve mainstream popularity. Scruff, Growlr, and Jack’d were founded the year after. Grindr users are a catch-all of different types, while Scruff and Growlr tend to a demographic of guys with beards, what one might reductively call “bears,” “cubs,” and “otters.” Jack’d users are primarily people of color, a phenomenon that was originally an accident. These users have flocked to Jack’d from other apps where they feel less included.

Dr. Jason Orne, an assistant professor of sociology at Drexel University, believes there’s a reason for the gap between what gay men of color experience online and the treatment they encounter in physical space. It’s called “social desirability bias.”

“If I know that people are observing me or that my answers are being read, I’m going to try to act in a way that makes me look like a better person,” claims Dr. Orne, who is also the author of the 2016 book Boystown: Sex and Community in Chicago. “If I were to walk out on the street in front of other people and yell these kinds of things, that would not be socially acceptable. But when I’m alone and not in the presence of other people, the social control created by observation would break down.”

Brandon Robinson, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, adds that “disinhibition effect” plays a factor. Because there’s a physical barrier between users and the people they interact with—represented by the screen of your iPhone or Android device—it invites a lack of empathy for those with whom one is engaging.

“If I don’t know who you are and I don’t have to physically see your reaction to what I’m saying, I don’t feel as bad as I would in offline spaces,” he says.

The Trump effect

Jesus Smith, a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas A&M, claims that in his research, he’s found a “dramatic decrease” in the number of profiles listing statements like “No Blacks, No Asians” in recent years. Although they are still common, there are fewer of them.

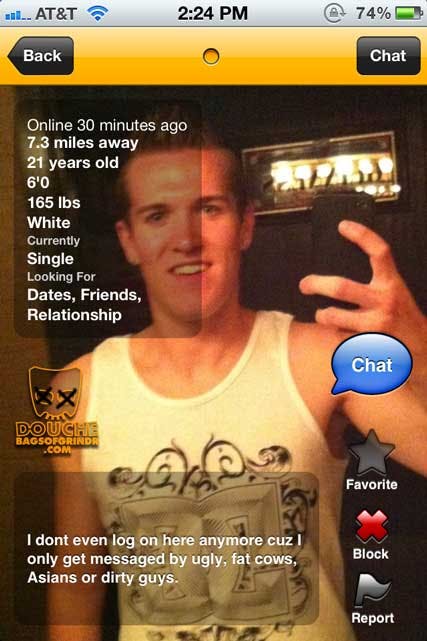

Smith, who came to this conclusion following a random selection of 630 profiles on Adam4Adam, says that the reason for this isn’t that gay and bisexual men have become more enlightened. It’s that websites like Sexual Racism Sux and Douchebags of Grindr have been calling out discriminatory behavior on hookup apps, which penetrates the veil of privacy.

“If you perceive that a lot of people are watching you online or are viewing your profile, you might adjust how you express your preferences,” Smith says.

Although Smith has found that many users have switched to a “coded” language in recent years that expresses racialized preferences through subtext (e.g., “I’m into rugby-type guys” or “My dream man looks like a Kennedy”), these incidents are no less prevalent. Kyle Turner, a 23-year-old film critic in Brooklyn, says men frequently assume that he’s submissive or a bottom just because he’s Chinese. One time a guy repeatedly told Turner how much he loved anime and K-Pop, and other men that message him pointedly ask where he’s from.

“I’ll say I’m from Connecticut,” Turner says. “That’s the answer you’re going to get.”

Although Turner claims that the majority of the negative experiences he has amount to microaggressions—or seemingly harmless statements that belie reductive assumptions based on race—Eliel Cruz argues that the comments he receives have only gotten worse in recent years. Cruz, a 26-year-old writer and activist, first logged onto hookup apps when he was a student at a Seventh-day Adventist college in Michigan. He says people rarely talked to him, and when he would reach out to say hello, hoping to make a new friend, users would say things like, “I’m just not interested in Mexicans.” Cruz is Puerto Rican.

But since Donald Trump announced his candidacy for the president in October 2015, Cruz says that he’s been frequently referred to as a “beaner” and a “spic,” especially when he’s traveling in the South for work. The worst comment, though, that he’s ever gotten was when another user told Cruz that he “wanted to fuck me before Donald Trump deported me.”

“When I first came out, I thought that the gay community would be welcoming and open to a new queer baby like me,” Cruz says, “but I’ve since realized that it wouldn’t be as accepting of me as I hoped.”

The struggle for inclusivity

As researchers explain, these apps don’t create racism. They merely provide a conduit to express the biases users might normally keep to themselves. But how do apps address the discriminatory attitudes expressed on their apps?

Each platform takes a slightly different approach.

Jack Harrison-Quintana, the director of Grindr for Equality, encourages users to report racist or abusive comments directed at them through the “Report” function on the app, which is located at the “upper right-hand corner on the offending profile.” Alon Rivel, director of Global Marketing for Online Buddies, the parent company that oversees Jack’d, says that the platform employs a 24-hour customer service team to monitor complaints. Any of the app’s users can call in and talk to a member of the Jack’d support staff at any time.

But Harrison-Quintana claims that “education is more powerful and effective than censorship.” That’s why Grindr, which takes a relatively hands-off approach to moderation, hopes to build a culture of inclusion through geo-targeting its users. Grindr for Equality, an initiative launched in 2012 to promote “justice and safety” around the globe, works with groups like the National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC) to inform queer men of color about issues that affect them—including getting tested for STIs. Although African-Americans make up around 12 percent of the population, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that this population comprises 45 percent of new HIV diagnoses. This information is essential.

But Sean Howell, the executive director of Hornet, says that his app has chosen to “somewhat limit freedom of speech” in order to build mutual respect. Howell launched the platform, which is most popular in Asia, in 2012 to give gay men around the globe a place “where you feel like you’re part of a community.”

“Nothing negative, especially around race, is allowed,” Howell says. “We’re not Reddit.”

If gay and bisexual men of color often feel excluded in digital spaces, Hornet’s unique approach to making marginalized communities feel welcome was to build affinity groups on the app. These groups allow people of color—whether black, Asian, or Latino—to build a positive community around race that they might lack elsewhere in their lives. For users in India, the app has 17 different trans-specific categories, and the developers have even considered adding groups like “social justice activists,” “communists,” and “radical fairy queers.”

Rivel claims that Jack’d has sought to reach out to communities of color through its marketing campaigns, which represent a diversity of ethnicities and types of bodies. He says it was important for the company not to just feature the “standard skinny, pretty white boy” but a variety of identities. According to Rivel, the company’s ads feature “people with a lot of tattoos,” “Asian guys,” “alternative folks,” and “people who look different.”

“There are a lot of faces to who Jack’d is,” Rivel says. “It’s not just one standard of beauty.”

Apps can do better

If Hornet, Grindr, and Jack’d have taken steps toward creating digital spaces where users can feel safe and comfortable, Robinson feels that there’s more that gay dating apps can do to combat sexual racism on their platforms. He points to the fact that most services allow users to select what they’re looking for in terms of race and exclude anyone who doesn’t fit that definition. When users search for guys in their area, they have the ability to automatically eliminate anyone outside of their preferred bubble of ethnicity.

“Gay men use these filtering systems to cleanse certain bodies from their spaces,” Robinson claims. “Putting this filtering system in there normalizes people’s racial desires—but then it also furthers those desires. If I put on Adam4Adam that I only want to see white people, but then every time I log on Adam4Adam all I see is white people, that’s just going to further my desire for white people. When it’s so normal on these sites, people don’t feel bad doing it.”

By eliminating these filtering systems, Robinson believes that people can learn to expand what they’re looking for and begin to find other types of people attractive. Although users who say that their racially exclusive desires are just a “preference” may believe that those desires are innate and hardwired into them, they’re not. These so-called preferences, as Robinson explains, are actually determined and informed by the culture to which one is exposed, whether that’s a gay community that centers white masculinity or a media that privileges certain kinds of beauty. Science has actually shown our tastes are “malleable and fluid.”

“If you’re not filtering out bodies of color, you might eventually find some people you find attractive,” says Robinson, who refers to this concept as the “contact hypothesis.” “If you are around people of color, you might be more willing to be friends with them or date them.”

Combating cultural notions about who is viewed as desirable is crucial because those myths are extremely damaging for all of those who are left out of a very narrow definition of beauty. Cruz says that for a long time, he would straighten the curls out of his hair and wouldn’t refer to himself as “Latino” on dating profiles in order to pass as white. Bojorquez says that he has learned to be “cautious” when interacting with other gay men because he’s afraid of being ignored “because of [his] skin color.” Hammond adds that he has “given up” on being viewed as sexy by other men.

“I’m not acknowledged as a human,” Hammond says. “If no one is going to like me because of institutional and structural racism, I’m going to have to figure out some other way for people to value me.”

All of us log onto the internet hoping to be “liked” or seen. But if nobody’s looking, it just makes you feel more invisible.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated for clarity.