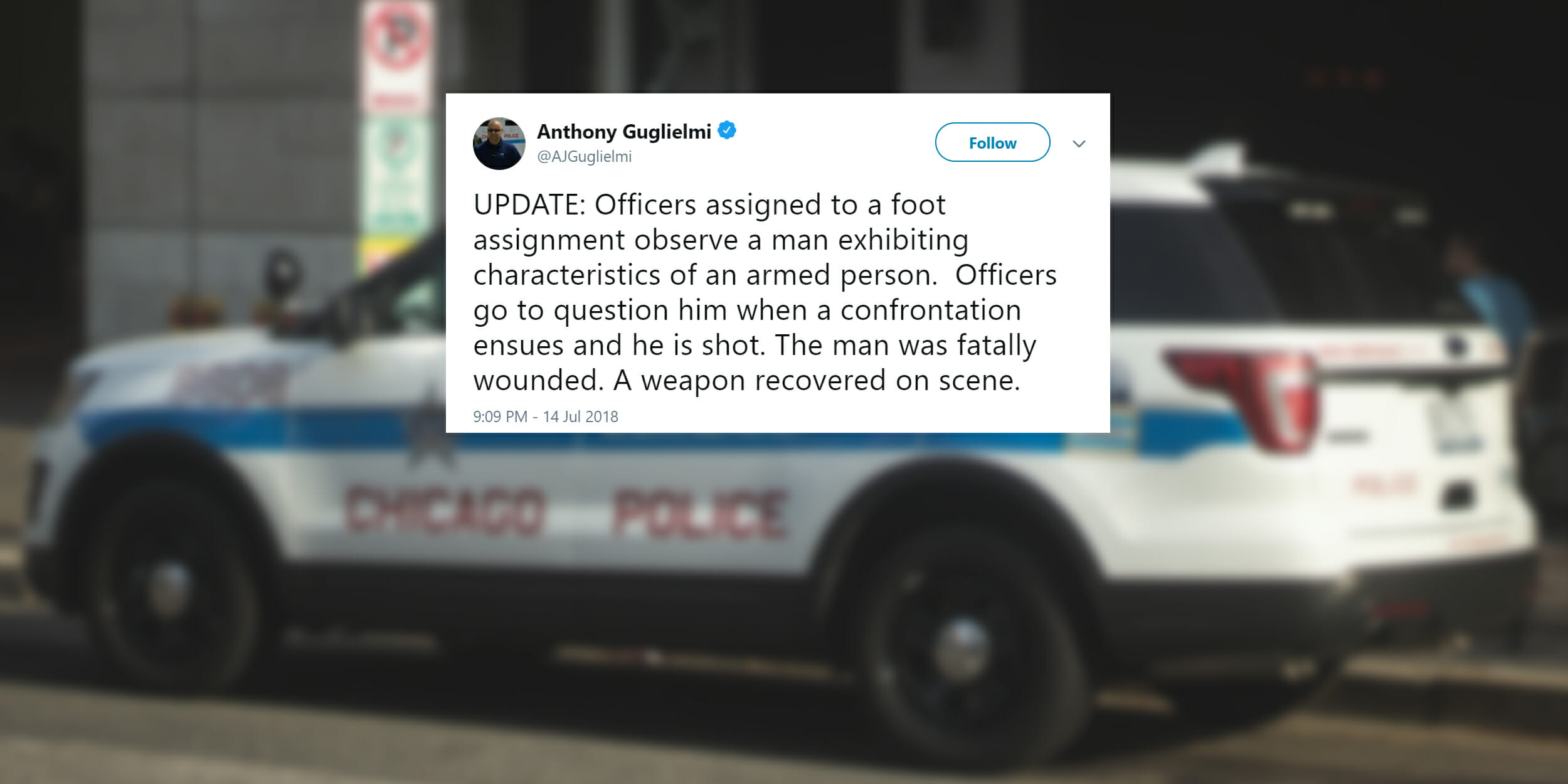

“Officers assigned to a foot assignment observe a man exhibiting characteristics of an armed man.”

This is how the Chicago Police Department began its explanation as to why a 37-year-old Black man was shot and killed by an officer.

They went on: “Officers go to question him when a confrontation ensues and he is shot. The man was fatally wounded. A weapon recovered on scene.”

UPDATE: Officers assigned to a foot assignment observe a man exhibiting characteristics of an armed person. Officers go to question him when a confrontation ensues and he is shot. The man was fatally wounded. A weapon recovered on scene. pic.twitter.com/8CJXu8m5pa

— Anthony Guglielmi (@AJGuglielmi) July 15, 2018

This phrasing is not only confusing, it also fails to describe the most critical aspect of the shooting: notably that the victim, Harith Augustus, was running away from the police when he was shot five times. A reporter on the scene wrote that “people outside the crime scene after the shooting claimed a white officer shot the man, a neighborhood barber, at least five times in the back as he ran away, and that the officer was taken away from the scene in a police vehicle afterward as the crowd formed.”

The reporter’s language is far more informative than the statement released by the police. But it was the police department’s language that was repeated by dozens of news outlets across the country. Outlets had the choice to prioritize one version of events or another, and opted to use the language from the Chicago PD press release.

Augustus’ death, and the protests that have since ensued, once again shine a light on the epidemic of police brutality and the racial double standards at work in America—being armed, after all, is legal. The reporting around the killing, specifically the willingness of journalists to adopt the preferred language of law enforcement, is also a problem.

“Exhibiting characteristics of an armed man” tells us very little other than possible racial profiling and is no justification for murder. Part of reforming the way police interact with society is demanding grammatical and moral clarity in the way we talk about incidents in which police shoot people. It is more difficult to fix problems that we aren’t talking about clearly.

Here’s where we should start:

Ban the term “officer-involved shooting”

When we talk about a murder, we usually say “a person shot someone.” When a police officer does the shooting, the incident is written about as an “officer-involved shooting.”

Several years ago, NPR’s Ethics Handbook issued a memo encouraging staff not to use the term. The organization concluded that it is one of those phrases that feel like “euphemisms designed by government to change the subject.”

In 2015, Washburn University law professor Craig Martin penned an essay outlining the problem with this kind of language, writing:

“This term serves to utterly obscure the role of the police officer, his or centrality to the incident, and indeed who is doing the shooting at all. The word ‘involved’ distances the police officer from the action. To say that a man is ‘involved’ in some incident is to insinuate that while he was implicated in some way, he was not at the center of the action, was not the primary actor in the event. Indeed, he might even be the victim.”

Not only does the term “officer-involved shooting” favor the police, it was created by the police. The term was used internally by the LAPD in the early 1970s, and its first known use in media was in the Los Angeles Times in 1977; it grew more common, however, after the 1979 murder of Eula Ray Love, a Black woman who was shot dead by two officers in her front yard. From there, it quickly became a new standard. (It bears mentioning that the Sentinel, a prominent L.A. Black newspaper of the era and still running today, has never used the term.)

Though “officer-involved shooting” is the most common way that a police officer is distanced from a victim in news writing (if you searched Twitter on the days following the shooting of Harith Augustus, you saw dozens of news outlets using “officer-involved shooting” in their headlines), there are other turns of phrase reporters use much in the same way. For example, articles often note that a police officer “discharged their weapon,” but fail to note that the bullets were discharged into a person, who then died. Because a police officer shot them.

Eliminate the passive voice

If you read enough coverage of police shootings, you start to see that these aren’t just isolated turns of phrase. These phrases are part of a broader campaign of using a passive voice to write about these incidents. It is clear that the goal, consciously or subconsciously, is to separate the police officer from the murder they have committed.

Passive voice involves constructing a sentence so that the object of an action is the subject of a sentence instead of the person performing the action. Some examples include “The road was crossed by the chicken” or “The unarmed black teenager was shot by the police officer.”

Again, Martin writes, “When articles or news reports go on to state that the person ‘died’ in the context of an ‘officer involved shooting,’ they imply or leave an impression of indeterminacy as to cause. Reports of death or disaster in the passive voice insinuate that the event was a result of some natural cause or inevitable chain of events.”

In writing about what he termed “copspeak” at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), media critic Adam Johnson identified a number of ways that passive voice has crept into reporting on police violence. For example, a local news headline in a report about Michael Brown’s killing in Ferguson, Missouri, read, “Teenager Shot, Killed in Ferguson Apartment Complex.” In the following article, the copy read, “A teenager was shot and killed. An officer from the Ferguson Police Department was involved in the shooting.”

These examples are not only in passive in voice, but also in its rightful subject—the police officer who murdered an unarmed teenager—is either not mentioned or is pushed to the following sentence.

Use language of justice

Passive voice, “officer-involved shooting,” and other phrases that complicate or shift blame like, “exhibiting characteristics of an armed man,” serve the same purpose: To downplay or remove the responsibility of law enforcement in the killing of innocent people.

Due to the highly segregated nature of our society, many people only interact with police brutality through reporting. Many of the people reading our nation’s largest newspapers or watching the nightly news may never even walk through a neighborhood where a police shooting has taken place. So, if we allow language like this to persist in reporting on police brutality, we are going to allow it to persist in many people's perceptions of police brutality.

It is likely then, that language like this decreases turnout at protests, signatures on petitions, and diminishes the total number of people who want to reform the criminal justice system. By design, people are made to feel like the problem is less immediate than it really is.

If we are going to work to end police brutality in America, we can begin by insisting that it is described, accurately, as police brutality.

The killing of Harith Augustus was not an officer-involved shooting, so let me correct that for you: A police officer shot and killed a Black man as he was running away.