In terms of communication, Africa has turned its greatest liability into its greatest strength. Because of its colonial history as a mine for natural resources, it has wound up with a much lower level of infrastructure than other parts of the world. But that has inspired the creation of an extraordinarily robust mobile system, one whose subscriber base has increased 500-fold over the last decade.

Any place that has an abundance of a particular type of technology is also going to produce a commensurate abundance of developers for that technology. As David Owino, a graduate student at Nairobi’s iLab at Strathmore University told me, “Our teachers tell us, ‘focus on the needs of your society’. But it’s also about the market.”

So if you’re an African mobile developer, you’re probably going to focus on social good. Not merely because you trying to help your society, but also because that’s where the lettuce is. If you’re from outside of Africa but work there, you’ll have to go along to get along, and that’s what the developers behind mWater have done.

mWater is a geolocational platform-agnostic mobile app that helps users find safe drinking water in their area. It also helps local water authorities, health professionals and others test and map water. In addition to the app itself, mWater has created and is continuing to grow a cross-platform, open-API global water database and a customizable sanitation and water health survey tool.

The API is noteworthy, as it will allow developers around the world to adapt mWater’s database and app tech to local needs.

mWater was a powerful enough concept that the people behind it found an angel investor, but a rather unusual one. They received $100,000 in funding not from a Sand Hill Road VC firm, from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)’s Development Innovation Ventures (DIV).

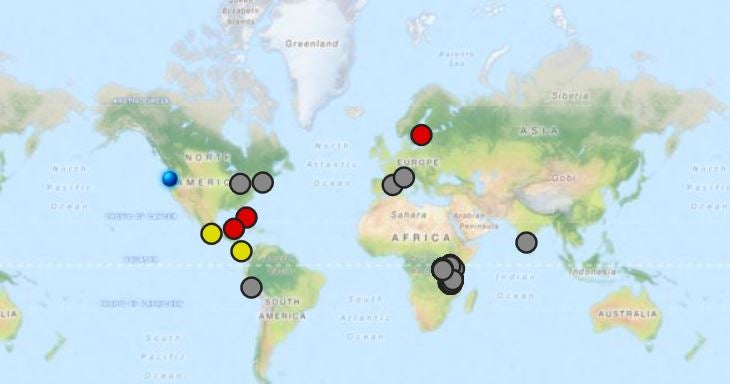

That’s right. USAID has a VC arm. DIV’s quarterly grant competition uses “ a tiered-funding model, inspired by the venture capital experience” to invest “comparatively small amounts in relatively unproven concepts, and continues to support only those that prove they work.” Their portfolio includes projects in 17 countries around the world.

“Right now, in Tanzania, more individuals have access to a mobile phone than a safe water source,” mWater writes in a press release on the DIV award. Their organization “leverages this mobile technology and open data to simplify the work of water quality testing and allow people to easily find the safest water sources near them.”

USAID will fund a nine-month project projected to help 90,000 people to allow mWater and partners in Mwanza, Tanzania “to establish a supply chain for the test equipment used with the app, and implement the mobile-based water monitoring system.” Local health and utility workers will use mWater’s app and a cheap $5 kit to test drinking water for contamination.

That test equipment was developed by mWater’s John Feighery, who worked on water issues for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

mWater began development of their app in 2011, launched its beta in 2012 and just last month launched the app officially. If the project makes it to “stage 2” funding the USAID’s DIV may elect to fund it again, to the tune of $500,000. If it makes it to stage 3, the funding will be in the millions. Because of the USAID funding, the app remains free for all users.

An app alone is no magic bullet, said Jamila Abass of Keny’as M-Farm. M-Farm is another mobile app which helps farmers work around the often unscrupulous middlemen and bring their products directly to market.

“People don’t drink dirty or contaminated water because they want,” she said, “they drink it because they don’t have a choice. Will mWater provide alternative water sources? Is it in their capacity to lobby stakeholders and make sure clean water is available? Do the people who are struggling to get clean water have the luxury of checking an app to get drinking water? Do the intended users worry about getting water or clean water? I believe such a solution will be better executed if the entrepreneurs are willing to get their hands dirty beyond just creating apps. At M-Farm, we do a lot more manual work than we create apps. This is not something we anticipated when we were starting. I can go on and on with questions but let me just conclude by saying: It is feasible, but an app alone will not cut it.”

Annie Feighery, mWater’s CEO and one of its co-founders, doesn’t exactly agree with Abass. Her point of view is market-driven.

“We pride ourselves on not being a traditional NGO (non-governmental organization),” she told the Daily Dot, “which come in to an area and provide services to solve all their problems, creating almost a shadow government. Ours is a market-based solution.” If it doesn’t work, users won’t support it.

Besides that, according to Feighery, more of the extreme poor live in cities today than in the “Peace Corps villages everyone think about.” According to studies mWater has made, the average African really does have a choice when it comes to water, on average a choice of three water sources. The key is to provide them with the information that will make their choice the most healthy one.

mWater is hardly the only mobile app solution to water issues. Splash, WaterWatchers, and others are also working to solve accessibility issues and hopefully competition will function in this sector the way it is supposed to in the private sector, driving developers to seek better and more efficient solutions for users.

“We’re very happy to have competition in mapping water locations,” said Feighery. Her app, she said, has a couple of elements that separate it from the pack. She describes mWater as a “multisectoral collaboration platform,” which allows users to consult it but also allows researchers and academics, government officials and health workers to contribute, letting the database know whether, for instance, a water kiosk is broken, or if the prices at a specific water source are tantamount to gouging. It is also the only app that can read and fully utilize water quality tests.

Photo by mWater