Hamza Jeylani probably didn’t expect to be pulled over after playing a game of basketball with his friends at the local YMCA. But Jeylani and his friends are black. That was apparently enough for a Minneapolis police officer to suspect the car they were in had been stolen.

As his friend pulled over the blue Honda Civic and Officer Rod Webber approached them, the 17-year-old hit record on his phone. Moments later, he was standing on the pavement in handcuffs. “Plain and simple, if you fuck with me,” the officer warned him, “I’m going to break your legs before you get the chance to run.”

“Can you tell me why I’m being arrested,” Jeylani asked.

“Because I feel like arresting you,” Webber said.

The four black teenagers later learned that Webber suspected them of stealing the vehicle. According to Jeylani, the owner of the car was driving and had both a license and insurance.

“I am scared,” he told the American Civil Liberties Union in a recent interview. “But I’m trying to keep my calm and understand the procedure that’s going on right now.” He hopes for justice, feeling wronged by the officer who said “the mean stuff” to him.

The officer who had threatened to break Jeylani’s legs was eventually suspended, but still receives a paycheck from the Minneapolis Police Department. The investigation into his behavior is ongoing.

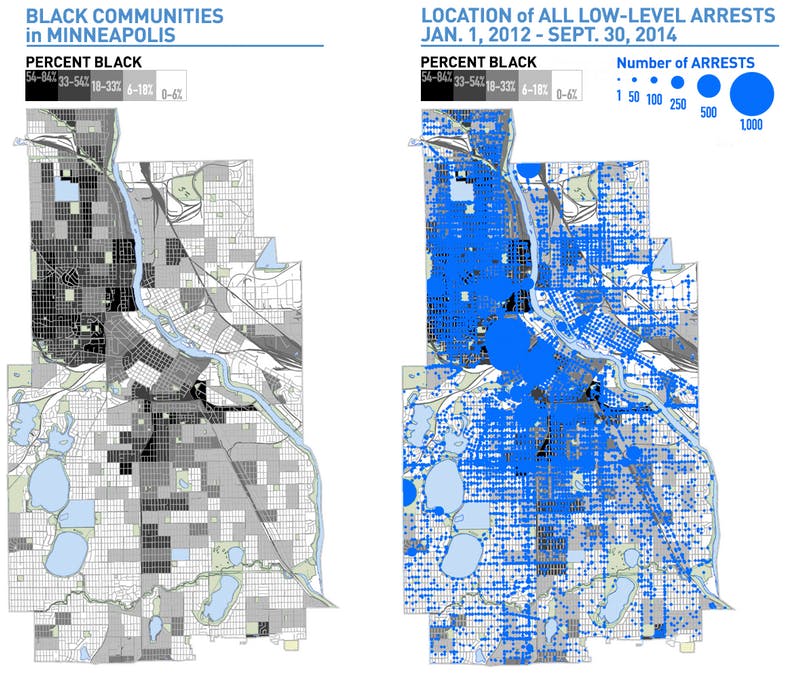

Unfortunately, Jeylani’s experience is far from extraordinary. Several months before his encounter with Officer Webber, the ACLU obtained arrest data from the Minneapolis police on roughly 97,000 low-level offenses. What the ACLU learned by examining the records perhaps justifies Jeylani’s fear. According to the researchers, there’s a huge disparity between the way police enforce the law in white neighborhoods compared to the teenager’s minority community.

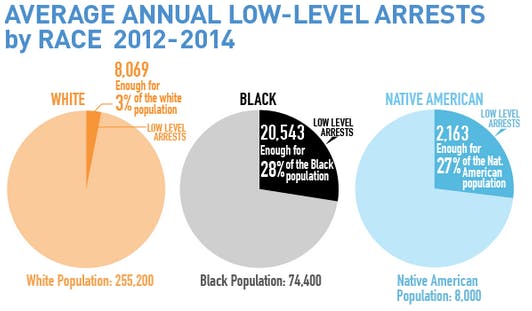

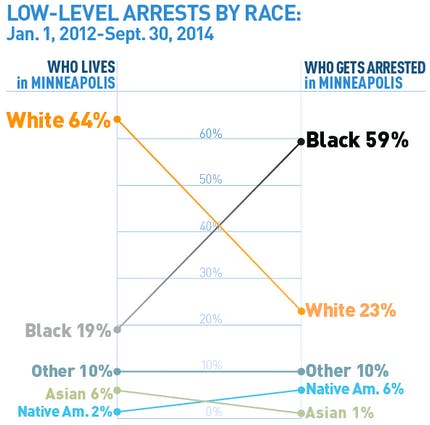

Black people in the city of Minneapolis, according to the ACLU’s final report, are 8.7 times more likely than whites to be arrested for nonviolent, low-level offenses, such as trespassing, disorderly conduct, or public intoxication. The research shows there are on average 20,534 black low-level arrests per year, compared to 8,069 for whites. While blacks make up 19 percent of Minneapolis’s population, they account for 59 percent of low-level arrests. Whites, however, make up over two-thirds of the city’s population, according to the report, yet only account for 23 percent of low-level arrests.

Professor Nekima Levy-Pounds, director of the Community Justice Project at the University of St. Thomas, told the Daily Dot that it’s not uncommon for black men in Minneapolis to be randomly stopped and searched and then given a ticket for spitting on the sidewalk or loitering in public.

What has “tough on crime,” broken-window policing, and a $1 trillion war on drugs bought America?

“The treatment of African-Americans at the hands of Minneapolis police is reminiscent of the ways in which blacks were treated during the Jim Crow era, except we’re in Minneapolis instead of Mississippi,” said Pounds, who also serves as president of the Minneapolis branch of the NAACP. “It is time for a paradigm shift in the city of Minneapolis with regards to our entire system of policing. A complete overhaul of the system is in order.”

When police officers like Rod Webber are captured on video behaving badly—a common occurrence nowadays, thanks to cellphone cameras—they’re often cast as “bad apples,” their conduct written off in the media as not reflective of the entire police force. The intentional and discriminatory targeting of black citizens, some say, is not systemic, but limited to a handful of officers.

It’s a theory that the ACLU researchers were more than willing to consider; unfortunately, it just wasn’t supported by the numbers, at least not in Minnesota. Yes, some of the Minneapolis officers are clearly more aggressive than others. Eight of them made more than 1,000 low-level arrests over a 33 month period. One in particular racked up over 2,000 such arrests. But even when these officers were removed from the picture, statistically speaking, the outcome shifted little.

“Without these top eight arresting officers, black people were 8.5 times more likely to be arrested for a low-level offense than white people, and Native Americans were 9.1 times more likely to be arrested for a low-level offense than white people,” the researchers found.

“There’s department-wide issues that have to change in order for these disparities to come down,” said ACLU staff attorney Emma Andersson, who works with the group’s Criminal Law Reform Project.

Andersson, once a law clerk for a federal appeals judge whose practice now includes litigation related to police practices, says the pervasiveness of the policing disparities in Minneapolis reflects the amount of reform that’s needed. “We need sweeping, radical change in the way police are doing their job, because there are sweeping problems,” she said.

“When we envision an ideal police force and police officer,” she continued, “we think about public safety threats, we think about them going after those who are committing acts of violence that endanger people. I don’t think that what we want to see is low-level behavior that is not a public safety threat being exaggerated, frankly, into what we are calling crime.”

Hours after the ACLU released its report, police officers responding to a carjacking call on the north side of the city were forced to open fire on two armed suspects. It was, as one department spokesman put it, a “day that never ends.”

Nevertheless, Police Chief Janee Harteau left her office that morning to sit down with Chuck Samuelson, executive director of the ACLU of Minnesota, for a 40-minute radio interview. While she took issue with the methodology behind the report—certain figures treated the multiple arrests of a single individual as multiple citizens being arrested, according to Harteau—she also acknowledged that black citizens were being arrested in higher numbers for certain low-level offenses. Poverty, she agreed with Samuelson, is at the “fundamental core” of the issue.

“I have not denied the disparities in those numbers do exist,” Harteau said during the interview. “We need to understand why they exist and take a deeper dive into those, and that’s what we’re doing.”

“It’s a conversation,” Samuelson told the Daily Dot later by phone. His office has been working with the Harteau and the members of the city council for almost year on the issue of police enforcement. “In all fairness,” he said, “[Harteau] has made a lot of changes that aren’t represented in that report, which we have applauded her for.”

The ACLU noted, for instance, that under Harteau’s leadership the Minneapolis police have instituted implicit bias training, created a pilot project for officer-worn body cameras, and have encouraged more community-oriented policing. She’s also currently working with the Department of Justice to review officer discipline proceedings. However, a civil review board with subpoena and disciplinary powers, one of the ACLU’s many recommendations, isn’t something Harteau is willing to consider, Samuelson said.

There are also efforts being taken by the city council to decriminalize a few low-level offenses, such as spitting and lurking, an ordinance that leaves plenty of room for dubious enforcement. By simply claiming that “intent to commit a crime” exists, for instance, police can issue a lurking citation to anyone who’s standing on public or private property. But the progress is slow. It can takes several months for the city council to revoke a single ordinance.

“This is a problem that’s been in this country for over 300 years,” says Samuelson. “It is not going to be solved in 30 days, or 60 days, or a year, and there’s no pill that we can give each other that’s going to eliminate the problem.”

The problem Samuelson speaks of is difficult to define. It can be labelled as injustice, or racism, or poverty, or all of the above; but as he points out, those are issues, created over generations, that can’t be solved with the wave of a magic wand.

After segregation became widely unpopular, politicians got “tough on crime,” which began the systematic targeting of low-level offenses, the tactic addressed by this week’s Minneapolis report. The enforcement began, for all intents and purposes, with the introduction of “broken window” policing: the theory that real criminals, the ones who truly pose a danger to the rest of us, rely on a climate of disorder and fear perpetuated by disruptive, albeit non-violent members of society—the “panhandlers, drunks, addicts, rowdy teenagers, prostitutes, loiterers, the mentally disturbed,” to quote the authors of “Broken Windows,” the 1982 article that coined the phrase.

“Many citizens, of course, are primarily frightened by crime, especially crime involving a sudden, violent attack by a stranger,” George Kelling and James Wilson wrote for the Atlantic. “This risk is very real, in Newark as in many large cities. But we tend to overlook another source of fear—the fear of being bothered by disorderly people.”

The “order-maintenance” model and its name are based on the theory that “if a window in a building is broken and left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken,” the authors explained. “Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.”

One in every 15 black men over the age of 18 is incarcerated. Only one in every 106 white men share the same fate.

However, Kelling and Wilson’s seminal article, although patronizing in its focus on the psychology of the citizen (e.g., chatting with cops gives people a “sense of importance”), also included the idea of community policing, which is the strategy of developing trust with the residents of a neighborhood. It was about cops getting out of their cars and walking their beats, gossiping with the citizens and listening to their concerns firsthand. Stripped of this essential element, the model becomes something else entirely. The police—not the drunken vagrants and obnoxious teenagers—become a neighborhood’s source of fear.

“The theory is if you take care of the minor stuff, the big stuff will take care of itself, more or less,” Samuelson says. “But what that involved, basically, is you would saturate high crime areas, or areas where there were problems, with police officers and you’d arrest everybody for anything. You would be an occupying army, and you’d behave like you’re an occupying army.”

So, what has “tough on crime,” broken-window policing, and a $1 trillion war on drugs bought America? A rate of incarceration that has outpaced the growth of the general population.

As of 2013, U.S. prisons held more than 2.2 million people, and roughly half are imprisoned for nonviolent offenses. According to the ACLU, one in every 15 black men over the age of 18 is incarcerated. Only one in every 106 white men share the same fate.

The truth, Samuelson says, is that Minneapolis police are arresting poor minorities in greater numbers because that’s what American police departments do. It is not a glitch; it is a policy that’s popular in every major U.S. city and it has been for a very long time.

Asked if the Minneapolis Police Department struggles with discrimination in its ranks, or if the department needs to reform any of its policies, a spokesperson told the Daily Dot in an email that the department does focus its efforts in high-crime areas, which are often impoverished.

“In terms of this particular issue,” the spokesperson said, “we can say that we put our officers where the public wants them to be, in high-crime areas. We go to the areas where people have called and are asking for help. Generally speaking, we have more violent crime in our most economically-challenged areas of the city and we have a stronger law enforcement presence.”

“One thing the Chief is asking,” the spokesperson added, “is where would our residents like to see our officers?”

Screengrab via ACLU Minnesota