The terrorist massacre that left 12 dead at the offices of satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris Wednesday morning may well have been a jihadist plot, with various reports claiming that the masked gunmen yelled “Allahu Akbar,” and that they had “avenged” the Prophet Muhammad. Minutes before the bullets flew, the publication had tweeted a comic panel of ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, sarcastically offering him their “best wishes” and toasting his “good health.”

Meilleurs vœux, au fait. pic.twitter.com/a2JOhqJZJM

— Charlie Hebdo (@Charlie_Hebdo_) January 7, 2015

A religious motivation for the attack on Charlie Hebdo wouldn’t be surprising. The weekly magazine, which has crossed every line in the name of free speech, had their headquarters firebombed in 2011 over an issue that featured a cartoon Muhammad on the cover—“100 lashes if you don’t die laughing,” he threatened—and has mocked any faith you care to name since its 1969 inception. But there’s another character at the center of today’s atrocity: the scabrous French novelist Michel Houellebecq.

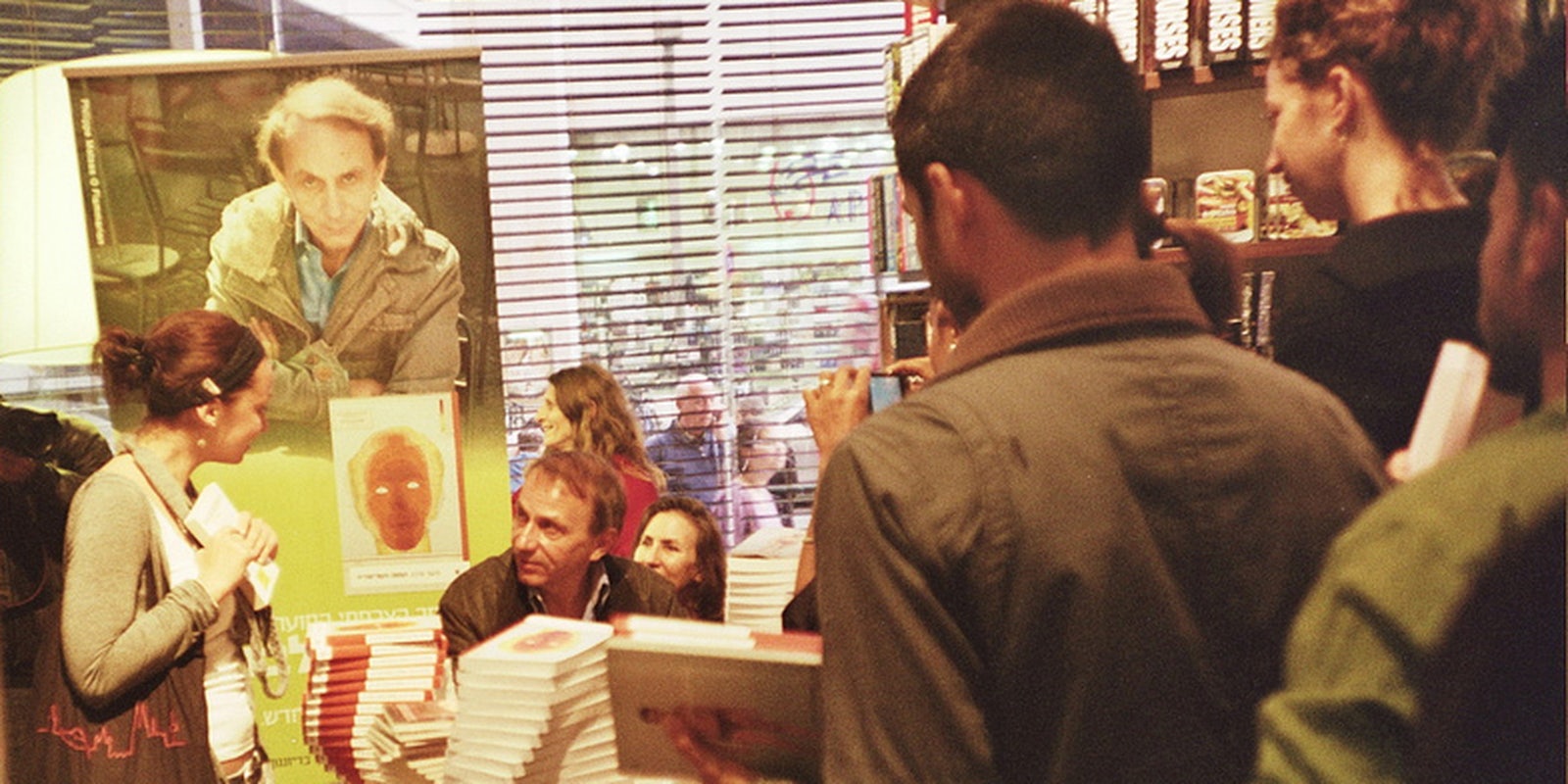

Houellebecq (pronounced WELL-beck) is a decorated literary icon in his native country and beloved by certain Francophile misanthropes in the English-speaking world. Each book since his debut has been a succès de scandale, drawing sharply divided reviews along with charges of racism, misogyny, obscenity, nihilism, and, of course, Islamophobia. They plumb the squalor of the world’s hypercapitalist endgame and project hallucinatory futures shaped by our worst fears, lusts, and frailties. They are punishing, fascinating exorcisms of bile.

#Houellebecq stirs passions with ‘Islamic France’ novel. http://t.co/qcCncPsVo4 pic.twitter.com/WbzovUDifZ

— The Peninsula Qatar (@PeninsulaQatar) January 5, 2015

His sixth and latest novel, Soumission (or Submission), envisions a France of 2022 that elects one Mohammed Ben Abbes as president and thereby triggers the top-down Islamification of Western Europe, with a focus on polygamy and female subservience. Already a top-seller on Amazon.fr, its release date just so happens to coincide with today’s eruption of terror, as well as a new Charlie Hebdo cover bearing a caricature of the writer as a clairvoyant mage: “In 2015, I lose my teeth,” he says. “In 2022, I do Ramadan.” The man who wrote the feature, Bernard Maris, was among those killed in Wednesday’s attack. (Another cartoon in the issue makes note of a “scandal”: that “Allah created Houellebecq in his own image.”)

They killed Bernard Maris, who wrote the cover story about Houellebecq. #CharlieHebdo pic.twitter.com/IV7Cexp51O

— Elif Batuman (@BananaKarenina) January 7, 2015

More images from the 1/7 Hebdo: “Scandal: Allah created Houellebecq in his own image” http://t.co/N4Ah6Vu1Vc pic.twitter.com/VI8iDb8gIG

— Elif Batuman (@BananaKarenina) January 7, 2015

But Houellebecq’s mastery lies in his talent for offending everyone at once: Submission may depict a controlling Islamic regime, yet it’s one where unemployment and crime are reduced to virtual nonexistence. “At the end of the day, things don’t go all that badly, really,” the career provocateur has stated in his typically offhand manner. (The same could be said for the plot of his novel The Elementary Particles, framed by a utopian society that has achieved asexual human reproduction and therefore no longer needs men). And the last time he waded into the Islamic question—a raw topic in France, where a population of nearly 8 million Arab Muslims are often at odds with virulently anti-immigration right-wingers—he found himself in court.

While promoting his 2001 novel Platform, which culminates in a terrorist assault on a third-world sex-tourism resort devised by western entrepreneurs, Houellebecq remarked in an interview that “Islam is the stupidest of all religions” and that the Koran is “badly written.” Accused of inciting religious and racial hatred in a trial that saw passages from Platform entered into evidence by the prosecution, he continued to muddy the waters: “There is no point in asking me general questions because I am always changing my mind,” he told the judges. The charges were eventually dismissed. Years later, he quipped that “The Koran turns out to be much better than I thought now that I’ve reread, or rather read it.”

Barista found a rival cafe’s apron in my hamper, showed herself out. Clement’s ears perk at the door, then me, and back to the television.

— michel houellebecq (@mhouellebecq) October 21, 2011

When militants opened fire on Charlie Hebdo staffers, then, for nothing more than a history of illustrations designed to shock and infuriate, the temptation was to see it as a Houellebecq narrative come to life—or a self-fulfilling prophecy. No doubt he’ll have an acidic soundbite on the whole tragedy in the days to come. But it will likely confirm what his biggest fans have always known: that he has no true interest in judging, predicting, or explaining political climates. All he does is reflect the disfiguring and endless battle to live on our own terms.