Opinion

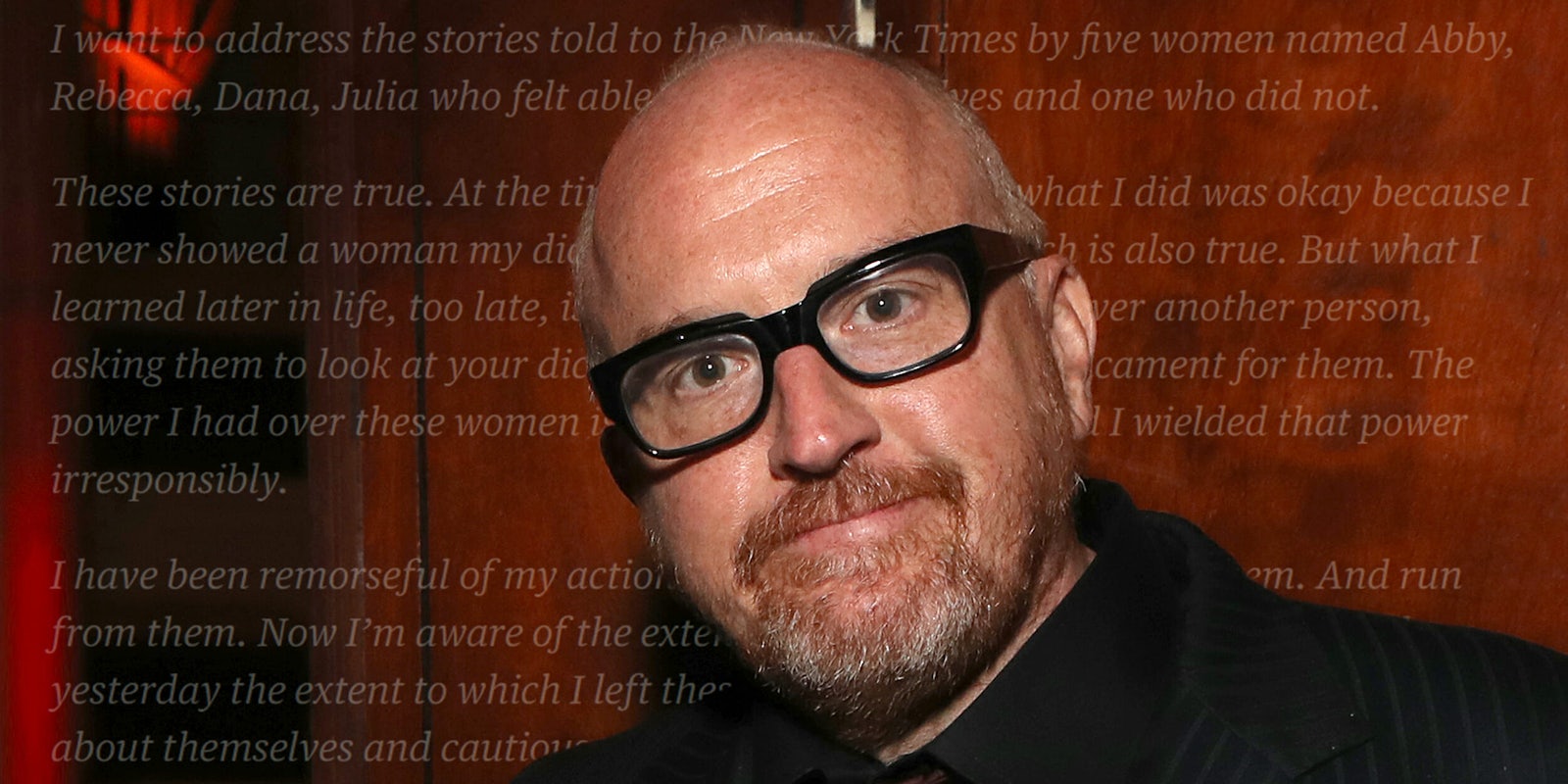

On Friday, Louis C.K. issued a public apology after the New York Times published accounts from multiple women that the comedian had masturbated in front of them. His apology has been criticized for its performativity—the rumors have been around for years, allegations that he previously called “not real” and only admitted to after he’d been caught.

His statement, however, was also striking for addressing what other celebrity men in comparable positions have tended to ignore: The propensity for serial sexual misconduct is about a power imbalance.

“These stories are true. At the time, I said to myself that what I did was okay because I never showed a woman my dick without asking first, which is also true,” he wrote. “But what I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them. The power I had over these women is that they admired me. And I wielded that power irresponsibly.”

C.K., whether he learned it “later in life” or not, knows he holds professional sway over fellow comedians, the women to whom he exposed himself included. He exploited his position with the understanding that, as Donald Trump put it, “When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.”

His grasp of this dynamic isn’t unexpected, though. It’s a trademark theme in his body of work. Much of C.K.’s comedy confronts social inequalities, like systemic sexism and misogyny, in ways critics have hailed as “woke.” But if we were to look carefully, embedded within that work is a contradiction between the way C.K. says he sees women and the ways he actually treats them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eko2weOmVis

There’s his creepily titled and now-canceled film, I Love You, Daddy, for example. That project featured a Woody Allen-esque character said to be sleeping with a child in pursuit of C.K.’s onscreen, teenage daughter. In one scene, a man pretends to masturbate, vigorously, to the voice of a woman on the phone, undeterred by a room full of people.

In C.K.’s FX sitcom Louie, too, the parallels are everywhere: Recall that controversial episode in which C.K.’s eponymous character, Louie, tries to manhandle Pamela Adlon into sexual submission, explaining to her that she actually wants to explore a romantic relationship with him, but because she can’t bring herself to acknowledge that truth, he’ll grab the reins. “I’m gonna take control and I’m gonna make something happen,” he says, backing her into a corner and pushing his puckered mouth against her firmly pursed, recoiling lips. His tiny private fist pump of victory after she finally flees suggests a misunderstanding about consent and authority. She did not want any of that, but that didn’t matter, because he wanted her.

Perhaps the most telling and widely overlooked interaction in that scene, though, is its opener: Louie finds Pamela asleep on his couch and spends a moment smiling down on her, until she cuts short his reverie, grumbling: “Please don’t start jerking off, I’m awake.”

In light of what we know now, these examples seem brazen as hell, like the actions of a man so convinced of his invincibility, he feels free to flaunt it before the entire world. Making art about the predatory behaviors you’ve been rumored to engage in for years speaks to sweeping assumptions about your own power and privilege.

Granted, we can’t take an artist’s work as a mirror image of the artist, and speculating about a stranger’s psychological motivations is just that—speculation. Cautioning against generalizations, David Ley, a clinical psychologist and author who has never interacted with C.K., sees the practice of masturbating in front of people you know don’t want to watch you masturbate as a self-reinforcing cycle of power and control. The more often a person engages in this behavior and gets away with it, he said, the more likely they are to do it again and the more likely they are to believe that the practice isn’t a problem, that it isn’t hurting anyone. They may, indeed, think that the person on the receiving end actually likes it.

To Ley, this kind of compulsive, exhibitionist masturbation reads as a narcissistic enterprise, and there’s one key aspect of narcissism that often goes overlooked. “The narcissist is actually plagued by self-doubt, and the core foundational thought or fear for the narcissist is that if they don’t constantly tell everybody how great they are, then nobody will think that they’re great, then people will think that they’re shit,” Ley told the Daily Dot. “The narcissist is oftentimes really, internally, horribly conflicted and just has a really deep-rooted sense of insecurity” and inadequacy.

“It is that personal struggle that we all have on some level, where we all worry, ‘If you knew what was inside my head, you would reject me,’” he added. “And it’s that kind of narrative that is so powerful in art and in comedy, especially comedy, because the point of comedy is to relieve tension and pain. We laugh at things that hurt.”

Lack of self-confidence, disbelief in his own worth—these are traits that characterize C.K.’s Louie, who, again, is a character and not a self-portrait. But the conflict between the shameful internal impulses and the exterior confidence does seem to seep onto the screen. Consider a few key monologue moments: In the episode where Louie assaults Pamela, C.K. spends much of his stand-up routine denouncing violence against women and explaining why it doesn’t make sense that men are in power. But within that latter bit, he passes a perplexing minute laying out a theory about the social-sexual hierarchy. Men are now in charge, he says, “because women were in charge, a long time ago, and they were really mean.”

“They were horrible,” he continues, to the whoop of agreement from one guy in the crowd. “You had to walk around naked and they would flick your penis and laugh at you. So we’re scared of them.”

What finally topples women from their place of authority is a man figuring out, “We can hit them!” in C.K.’s words. It’s a strange and unfunny interlude that makes you wonder if he really sees women as scary monsters bent on embarrassing men. And then, joking about violence as a tool of control sounds particularly jarring from a comedian whose most famous monologue is arguably the one in which he spells out precisely why men are “the number one threat to women.”

Maybe this kind of cognitive dissonance—guilt-producing friction between his purported respect for women on the one hand, and the apparent enjoyment of their physical discomfort on the other—helps explain why so much of C.K.’s bad behavior shows up in his comedy. It could be his way of working out those demons.

“It would make a lot of sense to me … that somebody who was struggling with ‘My sexuality is OK because these people are letting me do it’ and ‘Oh, but no my sexuality is bad because we shouldn’t be behaving this way and I’m imposing that on other people’—that conflict would play out in the person’s artistic production,” Ley said.

But believing it’s fine to wrestle with your misguided ideas about consent on the page or the screen is also an exercise in power. And it’s important for viewers and fans to recognize that. As Ley said, we shouldn’t separate that artistic production from its context: We live in a culture that enables and congratulates bad behavior.

C.K.’s proclivities have been a known quantity in the male-dominated comedy industry for years, and that industry seems to have consistently hushed up any brewing trouble and kept women fearful to speak out. Perhaps the explanation for C.K.’s brazenness isn’t any more complicated than the answer the comedian gave in his statement: He never had to think about editing himself, whether in person or on screen. His privilege afforded him the luxury of never being held accountable.