Opinion

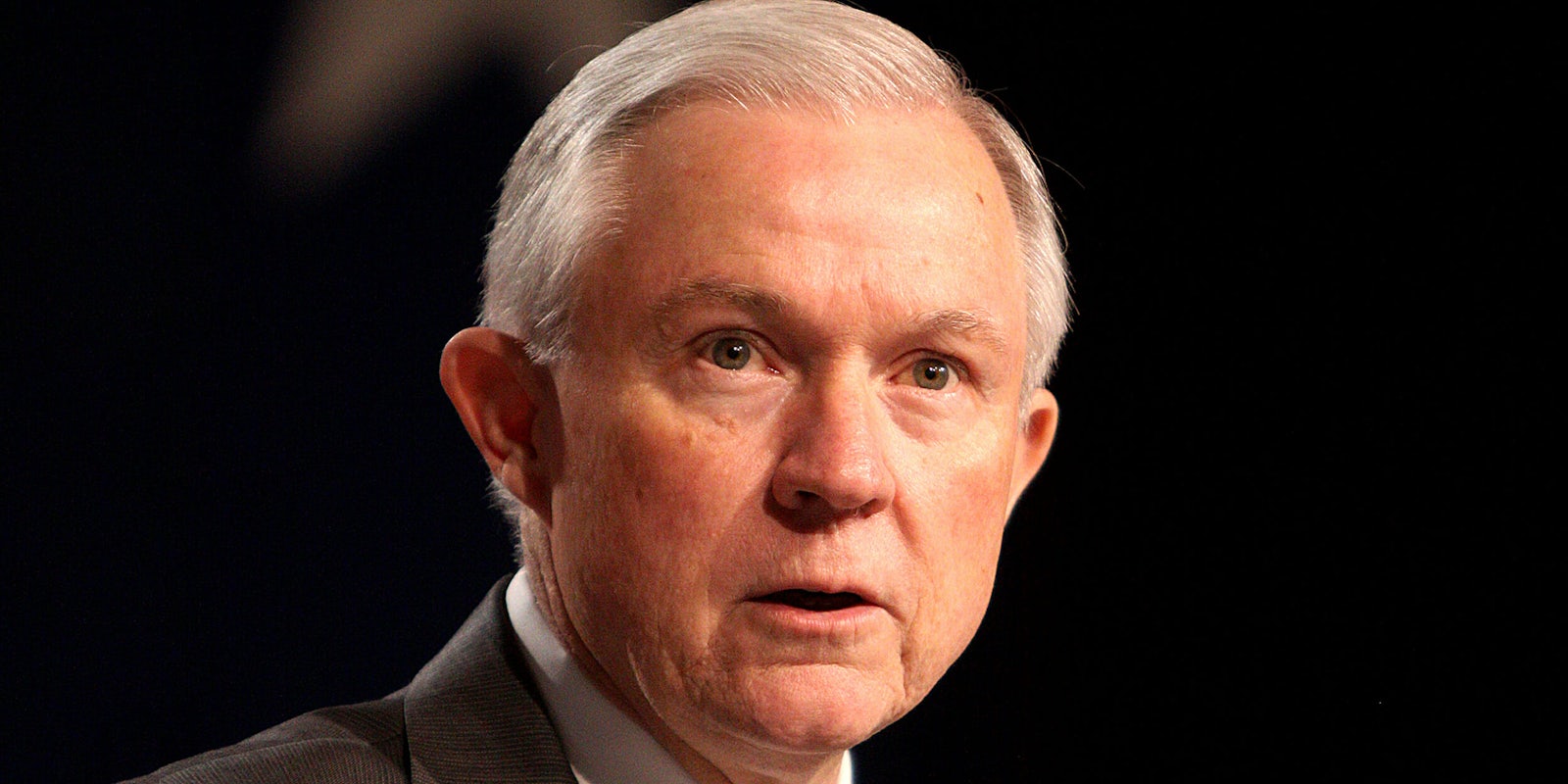

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has never seemed to see much value in women’s rights or civil rights. His latest decision—to bar victims of domestic violence from seeking asylum in the United States—does not break with tradition; indeed, the AG may have out-Sessions-ed himself with this one.

On Monday, Sessions overturned a 2016 ruling by the Justice Department Board of Immigration Appeals in the Matter of AB, which afforded asylum to an El Salvadoran woman on the grounds that her government could not protect her from intimate partner violence. Because he heads the Justice Department, Sessions can refer cases back to himself for final decision. In this latest one, he wrote:

An applicant seeking to establish persecution based on violent conduct of a private actor must show more than the government’s difficulty controlling private behavior. The applicant must show that the government condoned the private actions or demonstrated an inability to protect the victims.

Further, he stated, an asylum applicant must belong to a “particular social group” whose members “share a common immutable characteristic,” are “socially distinct within the society in question,” and are persecuted because of it. If the body persecuting them is not the government, Sessions clarified, then the person seeking asylum must demonstrate “that her home government is unwilling or unable to protect her.”

The El Salvadoran government arguably checks both boxes of being “unwilling” and “unable” to protect victims of domestic violence. El Salvador ranks high among the world’s most dangerous countries for women: According to the Guardian, 152 women were reported murdered there between January 1 and May 1 of this year—but as one El Salvadoran woman noted in a recent New York Times op-ed, official counts only include “bodies that are taken to morgues … not those found dismembered in clandestine dumping grounds.”

Although it does have laws criminalizing domestic violence on the books, the tiny country does little to enforce them. According to Splinter, five cases of domestic violence are reported daily in El Salvador, yet a vanishingly small 1 percent of all (reported) violent crimes committed against women eventually translate to a conviction. The statistics are particularly damning for young women: As the Atlantic has reported, gangs (like MS-13) target girls with special vehemence, forcing them into sexual relationships that often turn violent. Notably, Sessions’ decision on Tuesday also singled out gang violence as a factor applicants could no longer rely on to win them asylum.

Although the Trump administration likes to paint pictures of borders overrun with migrants all attempting to snake their way around immigration laws—Sessions used the word “stampede”—according to the Times, 10 applicants were denied asylum for every one who eventually succeeded. At least that was the case in 2016, the year the El Salvadoran woman in question saw the BIA grant her appeal.

Precedent for domestic violence-based asylum stems from the BIA’s 2014 decision in the case of Aminta Cifuentes, a Guatemalan woman whose husband routinely raped her and beat her badly enough she suffered broken bones. Before she left her country in 2004, she contacted authorities, who reportedly refused to intervene—even as her husband threatened to kill her for calling them. Cifuentes’ position is not unique, especially for women in the so-called Northern Triangle of Central American countries: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In 2017, one United Nations official classified the domestic violence situation in those nations as a “hidden refugee crisis,” so dire was the need of women to flee.

Of course, mention of anything resembling a refugee crisis seems enough to set Sessions’ teeth on edge. Infamously hostile to immigrants from Muslim-majority countries, Sessions has lately turned his attention to “caravan” migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. His “zero tolerance policy” on people caught crossing the border with children—the one that would separate families—bodes particularly badly for those who most often undertake caravan journeys: Women and their children, hoping to escape violence at home.

But gender-based violence has never seemed to have bothered the AG much. At age 71, Sessions has enjoyed a perplexingly long political career, and at no point has he exercised anything like respect for women’s rights. In 2014, when the Senate voted to reauthorize the 1994 Violence Against Women Act—updated to include expanded protections for migrant women seeking refuge from abuse, LGBTQ victims, and Native American women abused by non-Native people on tribal land—Sessions said no. He also voted against the Military Justice Improvement Act, which would’ve made it easier for service members to receive an objective investigation into sexual assault allegations. And when an incriminating audio recording surfaced late in the 2016 presidential race, featuring Donald Trump bragging about grabbing women by their vaginas without permission, Sessions downplayed his candidate’s actions.

“I don’t characterize that as sexual assault,” he told reporters at the time. For reference, the department over which Sessions presides defines sexual assault as “any nonconsensual sex act.” The Office of Justice Programs defines the term as “unwanted sexual contact between victim and offender,” which can “include such things as grabbing or fondling,” along with “verbal threats.”

According to the National Women’s Law Center, Sessions has consistently stood against anti-discrimination measures that protect women’s equal right to vote, and to access education, employment, and housing. He has openly opposed the Voting Rights Act, the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, and the Employment Non-Discrimination Act.

Additionally, Sessions has characterized Roe v. Wade as a “colossally erroneous” Supreme Court decision. Although he promised not to attack the limited right to abortion it established nationwide, he did go after an undocumented minor known as Jane Doe in October, after ACLU attorneys wrestled her the right to get an abortion in Texas. The DoJ subsequently petitioned the Supreme Court to overturn the decision (strange, as contrary to the administration’s position, an abortion cannot be reversed) and punish Doe’s lawyers. With all that in mind, who can feign surprise at Sessions’ Monday ruling?

But the words he chose shoot holes in his own argument. The habitual ill-treatment of women in El Salvador—treatment the government tacitly sanctions—arguably constitutes a series of human rights violations against a group identified on the common characteristic of their gender. Yet Sessions has always tended toward the draconian in dealing with women in crisis. Abuse doesn’t seem to strike him as much of a problem.