To draw a reductive binary, there are two types of people on the Interwebs: Those who only look at viral content for its entertainment value, without considering whether the events portrayed actually occurred as depicted, and those who are physically unable to enjoy something they’ve stumbled upon online if they suspect it might be bullshit.

The last week should probably push a lot of people into the latter camp. In the span of a few days, the Internet was taken with a veritable flood of bullshit, fake stories propagated by unscrupulous scammers looking to take advantage of a scrupulous public’s willingness to click on pretty much anything more interesting than the work they’re desperately trying to avoid actually doing.

For example, a woman who claimed to have gotten plastic surgery to get a third boob implanted between her original two was, according to actual plastic surgeons, almost undoubtedly a complete and total fabricaton. And reports that members of anarchic message board 4chan responded to actress Emma Watson’s speech to the United Nations about gender equality by threatening to release nude photos of the Harry Potter star turned out to be the work of of serial viral scam artists SocialVEVO.

The list goes on.

Basically, the Internet is a minefield of question marks. Aggregation sites, many of which have a tendency to uncritically post about viral content without checking its veracity, only make the situation worse by lending an air of journalistic credibility to a piece of content essentially no more trustworthy than something selected at random in a game of YouTube roulette.

Luckily, just as the Internet has democratized news gathering, it has also democratized the fact-checking process. Even without the institutional might of, say, the New York Times behind you, it’s now easier than ever for everyday Internet sleuths to poke holes in latest fraudulent viral craze.

The following are tips cobbled together from my own experience reporting on viral content at the Daily Dot, the European Journalism Centre’s free-to-read Verification Handbook, and advice from Storyful Executive Editor David Clinch—whose company certifies the veracity of, and then helps to monetize, online videos.

What to do when a YouTube video seems too good to be true?

The most important thing to keep in mind is that, thanks to YouTube’s profit-sharing program with successful video creators, there’s actually an economic incentive for people to put up fake videos that attract a critical mass of eyeballs. That is, of course, in addition to the sheer, childlike joy of trolling a credulous populous. YouTube gives people the ability to take a cut of the advertising revenue generated on their videos once those clips hit a certain number of views. The famous ?David After Dentist” video, for example, netted the the family of its then pre-adolescent star at least $150,000.

When explaining what to watch out for when casting a critical eye on a viral video, Clinch points to two famous recent YouTube-based hoaxes that even fooled a lot of the media when they first broke into the public consciousness.

The first is a video, dating back to late 2012, allegedly depicting an eagle snatching a baby from a Canadian park.

?For one, the eagle was too good to be true,” insists Clinch. ?Secondly, what we really look out for is if something like that really happened, someone would notice. Somebody would be talking about it; it would be in the local news. So, when you see something like that, which is an events-based thing, you should think to yourself, ‘what are people saying about it?’ You can go on Google or Twitter and see if it’s being reported on by local news. In this case, it just wasn’t. The video just kind of popped up out of nowhere.”

The moral of that story is if a video at first blush seems a little too perfect, it’s a good idea to do a little forensic work to see who initially discovered it before hitting the share button. Blogs will often give a ?hat tip” at the bottom of a post as a way of acknowledging how they first discovered a piece of viral content. Following a trail of hat tips back to the original source is often a good way to determine if a piece of content has ever actually been independently verified.

?The twerking girl video is somewhat less sophisticated,” Clinch explained, ?but you would expect that if somebody had posted something like that and had put their name on it on YouTube, you would expect them to be a real person, who was also on Facebook or on Twitter and had a name or a phone number.”

The person who supposedly uploaded the this particular video, Caitlin Heller, had never posted a single other video to YouTube before or since. Clinch’s team looked into it and couldn’t find any other traces of Heller’s digital footprint online—no Facebook page, no Twitter account, nothing. ?There was no other evidence that this person was real,” he said. ?That gave us a red flag.”

A good tool for tracking people down online is Pipl, which allows instantaneous access to an instantaneous cross-referencing database of names, email addresses, phone numbers, and social-networking profiles.

Storyful’s viral detectives were able to discern that the twerking video was likely a fraud when its views were still in the hundreds, rather than the millions of hits the clip would eventually generate.

Even so, just because a YouTube account has posted a bunch of videos prior to a suspicious viral hit, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re legit.

There are a whole community of YouTube accounts called ?scrapers” that just rip off content found elsewhere on the video-sharing site and then reupload it to the site as if it were their own original work. If you go back through a user’s upload history and see that they’re clearly just resharing other people’s stuff for their own personal gain, it should be a sign that the particular piece of content you’re looking at isn’t original. It could be years old or, at the very least, never had its veracity vouched for by the person who uploaded it.

Every picture tells a story. Some of those stories are made up.

The first thing to do for photos, especially for warzone photos and those in contexts with which you’re unfamiliar, is to do a reverse image search.

Glancing at a photo and instantly being able to tell whether or not its been digitally edited can be difficult, if not impossible, for people who haven’t spent years of their lives frowning at a copy of Photoshop on their computer screens. However, determining if a picture someone claims was shot in last week in Syria was actually taken during the Lebanese Civil War circa 1986 may be a little bit more straightforward.

To do a reverse image search, find the url of the isolated image you’re interested in learning more about and enter it into Google. The search engine will pop with a link asking if you want to ?search by image.” Click it and Google will show you all of the other times the image has appeared online. Wade through the results and see if there are any instances of that video popping up prior to this specific instance in an entirely different context.

Writing in the Verification Handbook, BBC social media and user generated content editor Trushar Barot insists one way to learn a lot about a photo is to examine its metadata, which can tell you everything from the make and model of the camera it was taken on to the day and time the image was captured.

While this information, often referred to as ?EXIF” data, can be extracted by looking at the picture in a photo editor like Photoshop, there are also free, easy-to-use websites such as FindEXIF.com that pull out a photo’s metadata in seconds.

This methods isn’t foolproof; social networks like Facebook and Twitter remove much of the metadata of photos uploaded by their users. However, doing a reverse image search on the photo in question can often produce a clean copy.

Did he really just tweet that?

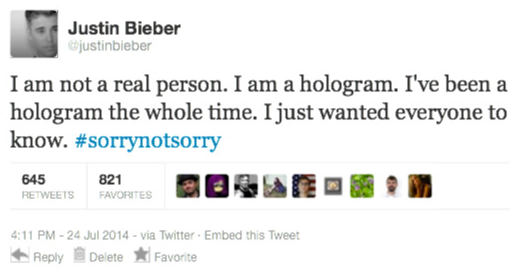

Just because you see a tweet embedded in a story that doesn’t necessarily mean the person it’s supposedly from actually wrote it. Take, for example, this tweet from increasingly insufferable Canadian teen heartthrob Justin Bieber:

A quick glance at this tweet and you’d think that the ?Baby” singer just admitted to not actually being a real human being—like Japan’s holographic pop idol Hatsune Miku. Yet, by all indications, Bieber is actually a flesh-and-blood human being. I created that tweet using the site LemmeTweetThatForYou.com, which allows users to construct a fake tweet supposedly from any user on the social network.

The first giveaway that the hologram tweet was fake should be that Bieber’s name lacks the little blue-and-white check mark next to it identifying it as a verified account, which means the social network has taken steps to make sure it is actually controlled by the real-life person it purports to be. Compare the previous Bieber tweet to the one below, written by the singer himself:

I love music

— Justin Bieber (@justinbieber) July 24, 2014

However, not everyone on Twitter has a verified account, the vast majority just have to be taken at their word. In that case, it’s advisable to scan through some of the account’s other tweets. Do those tweets seem like they came from the person who the account says it represents? Could it possibly come from a satirical parody account?

On the Internet no one knows you’re a fraud

Even if there’s a video, picture, or tweet that sets off your bullshit alarm, there’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to unequivocally debunk it. Over 100 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute, and viral detective work can be a long, hard slog without much personal payoff of the average Internet user.

But there are lots of sites on the Internet, from Gawker’s Anti-Viral blog to the Daily Dot’s own efforts, making valiant efforts to separate truth from fiction. Googling the title of a viral video or photo along with the words ?fake” or ?hoax” may lead you to discover that someone’s else has already put in the requisite virtual legwork.

The grandaddy of all online hoax exposure sites is invaluable Snopes.com. Launched in the mid-1990s by Barbara and David Mikkelson, Snopes has been expertly debunking all kinds of viral phenomenon and urban legends for nearly two decades. If something is a fake on the Internet, there’s a good chance that the sainted souls at Snopes have probably written about it.

Nevertheless, there are still some piece of viral content that not even the professionals have been able to definitively disprove.

?There’s one out there in Australia where there’s a guy who jumps into the water in Australia and a shark swims up right next to him,” Clinch said. ?I’m still convinced that’s a fake, but I haven’t been able to prove it.”

?The video has something like 25 million views and the guy has made loads of money on YouTube, but nobody knows who he is,” Clinch added. ?There are some parts of it just don’t add up, from the camera angle to what people are saying in the video. It just doesn’t add up because nobody reported on it locally; it doesn’t add up because there’s nobody with that name; it doesn’t add up because there’s nothing else on the YouTube account.”

The key is, he says, is to always be skeptical.

H/T Columbia Journalism Review | Images sourced from Wikipedia | Remix by Max Fleishman