Leading U.S. social networks have cut access to one key police-surveillance tool after pressure from civil rights groups, but dozens of other similar online-spying tools remain available to police.

Citing privacy concerns raised by the American Civil Liberties Union, at least three social media platforms this week suspended the commercial access of Geofeedia, a private company whose social-media-surveillance service is licensed by more than 500 U.S. law enforcement agencies.

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—reacting to a report by the ACLU of Northern California—have cut off Geofeedia’s access to specialized feeds that help police comb through and store social media posts in ways typically reserved for, as ACLU put it, “media companies and brand purposes.”

The effect of the social networks’ decision to cut ties with Geofeedia will be immediate and widespread, likely forcing thousands of police departments across the United States to alter the ways in which law enforcement officers are able to use social media as a tool for intelligence gathering and crime prevention. The decisions by Facebook and the other companies will also likely impact several federal agencies, including the U.S. Departments of Justice and Homeland Security.

The ACLU wrote on Tuesday that records show police have relied on data provided to Geofeedia by Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram when monitoring protests in Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri, in the aftermath of police shootings in those cities. The Daily Dot reported exclusively in September that the Denver Police Department paid $30,000 to secure a one-year subscription to Geofeedia, potentially violating a prior agreement to stop collecting information on protesters not suspected of crimes.

While in use by hundreds of local police agencies, Geofeedia is merely the tip of the iceberg: When shopping for a product that collects, analyzes and stores data on U.S. citizens through social media, local, state, and federal agencies have more than a dozen software products to choose from.

Based on information in the @ACLU’s report, we are immediately suspending @Geofeedia’s commercial access to Twitter data.

— Global Government Affairs (@GlobalAffairs) October 11, 2016

Bypassing privacy settings

With access to back-end developer tools, the surveillance platforms purchased by police provide local, state, and federal agencies with access to data on users not easily obtainable by the general public, an issue that runs counter to arguments that police are merely gobbling up information willingly surrendered by the millions of Americans with public social media accounts. Internal police records reviewed by the Daily Dot, which were provided by Working Narratives of North Carolina, revealed that one of Geofeedia’s goals is to bypass the privacy options offered to users by services like Facebook.

During a conversation with the Durham Police Department in North Carolina in 2014, for instance, a Geofeedia representative, after being told the police department wasn’t interested in the product due to budgetary concerns, claimed Geofeedia was working on ways to help police access “private Facebook posts.” That capability would be available by September 2014, the representative said. The promise of this option captured the police department’s attention; privacy settings, particularly those that prevent posts from being tagged with locational data, hinder police tracking. The solution, according to Geofeedia, was to enable police to tie in “dummy” accounts—sometimes called “undercover accounts”—in order to “track persons of interest across all of their social media sites (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) whether their posts are geo-tagged or not.”

In a statement to the Daily Dot, Twitter said it actively reviews third-party access to its service by companies like Geofeedia to ensure they are complying with the company’s policies. The spokesperson added, “and we take action—including termination of access—where appropriate.”

A Facebeook spokesperson similarly cited Geofeedia unauthorized use of its data as the reason for severing its ties with the company.

“This developer only had access to data that people chose to make public. Its access was subject to the limitations in our Platform Policy, which outlines what we expect from developers that receive data using the Facebook Platform,” the Facebook spokesperson said. “If a developer uses our APIs in a way that has not been authorized, we will take swift action to stop them and we will end our relationship altogether if necessary.”

Geofeedia did not respond to a request for comment.

Though the technique involving “dummy” accounts is not disclosed at length, it appears other services have used the work-around, including Snaptrends, a product very similar to Geofeedia—and, in fact, preferred by many police agencies—according to the emails of a crime analyst at the Savannah-Chatham Metro Police Department in Georgia.

By the summer of 2014, Snaptrends was being used by at least hundreds of local and federal law enforcement agencies, in addition to Homeland Security-run Fusion Centers and the “High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area” (HIDTA) program, the emails show.

Snaptrends could not be immediately reached for comment.

A crime analyst with the Phoenix Police Department in Arizona claimed in an email that Snaptrends was sold to his department with the promise that the program could defeat user efforts to conceal their locations on Twitter. “The explanation I got, after pushing for it, was that they have exclusive access to Twitter back end,” wrote the analyst, who noted that he had also tried Digital Stakeout, a product offered by Lexis Nexis. Lexis Nexis is the developer behind another popular platform for accessing historical legal records typically used by lawyers and journalists (including those at the Daily Dot).

The claim that Snaptrends has access to private backend data about Twitter users is entirely bogus, according to a highly-placed source at Twitter, who said such access would violate a longstanding company rule prohibiting the sale of user data for surveillance purposes.

“The thing that sold me on Digital Stakeout was the ability to monitor your undercover accounts,” a law enforcement official in Osceola County, Florida, said. “I will say this, that we did not expect the amount of data we would get,” he added. “It’s overwhelming and we don’t have an analyst specifically assigned to do social media only.”

Last year, Social Sentinel, a company that provides law enforcement with “social media threat intelligence alert solutions,” passed around guides to help police inform their decision about purchasing social media monitoring software. The first piece of advice Sentinel offered: The monitoring service chosen by police should have an existing data agreement with Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms.

“Think about it this way—if you were in court and were asked how you gathered information that led you to the issue at hand, would you need to ensure that the information received came from a legally defensible method? Yes? Great, then every alert that stems from your service should meet that standard,” Sentinel said.

Sentinel offered the following definitions for ways in which social media monitoring can access data:

- Scraping— “A site scraper is a type of software used to copy content from a website. Take a look at most websites’ Terms of Use and you will find that almost all of them prohibit scraping. If you need to ensure that your social media monitoring or threat alert service provider has obtained legal access to the information being passed to you, make sure you ask whether the provider includes data that is scraped from websites in its results. Are there times when this might be allowed? Yes—in some instances, they might contract with your prospective service provider to allow that party to scrape data from their site, but you must ensure that, if this is a practice used by the potential provider, that your provider has contracted with the company not just to scrape their site, but also to pass, lawfully, all data secured via scraping to you as a third party.”

- Firehouse— “This is a term that is specific Twitter. It’s their complete stream of social media posts. GNIP is owned by Twitter and is Twitter’s sole data representative. GNIP provides access (via an API—see below) to Twitter’s firehose and to the data of various other social media sites. Most social media monitoring and threat alert companies have a contract with GNIP to access Twitter’s data as well as many (but not necessarily all) of the social media and blog sites that GNIP represents. When interviewing prospective social media monitoring and threat alert service providers, make sure that they all have access to the COMPLETE Firehose. GNIP offers different tiers that can help media monitoring and threat alert service providers sample data in a less expensive manner—which is sufficient for a company that is looking to investigate how their brand is faring or for a researcher that needs an audit of what social media has to say on a given topic, but is incomplete and unacceptable for a public safety team that needs to identify threats. For that, you need access to the entire data set.”

- API— “API is an acronym for ‘Application Programming Interface.’ An API defines a set of routines, protocols, and tools to specify how software components should interact. For social media monitoring and threat alert service providers, working with a social media site’s API means that data is being facilitated by the API to define what information will be shared between the two, how often, and whether there are any restrictions or special allowances associated with the data being accessed.”

Weighing the pros and cons

Other records reviewed by reporters show that police are fairly skeptical about the benefits of social media monitoring, often debating their purchases by engaging in lengthy reviews of products like Geofeedia, LifeRaft, Media Sonar, CES Prism, Snaptrends, and others. Before deciding on a platform, police will solicit advice from other departments using a nationwide mailing list for crime analytics restricted to law enforcement personnel. Police weigh the cost, usability, and anticipated benefits of their purchase ahead of time, much in the way consumers compare products and read reviews on Amazon before opening their wallets.

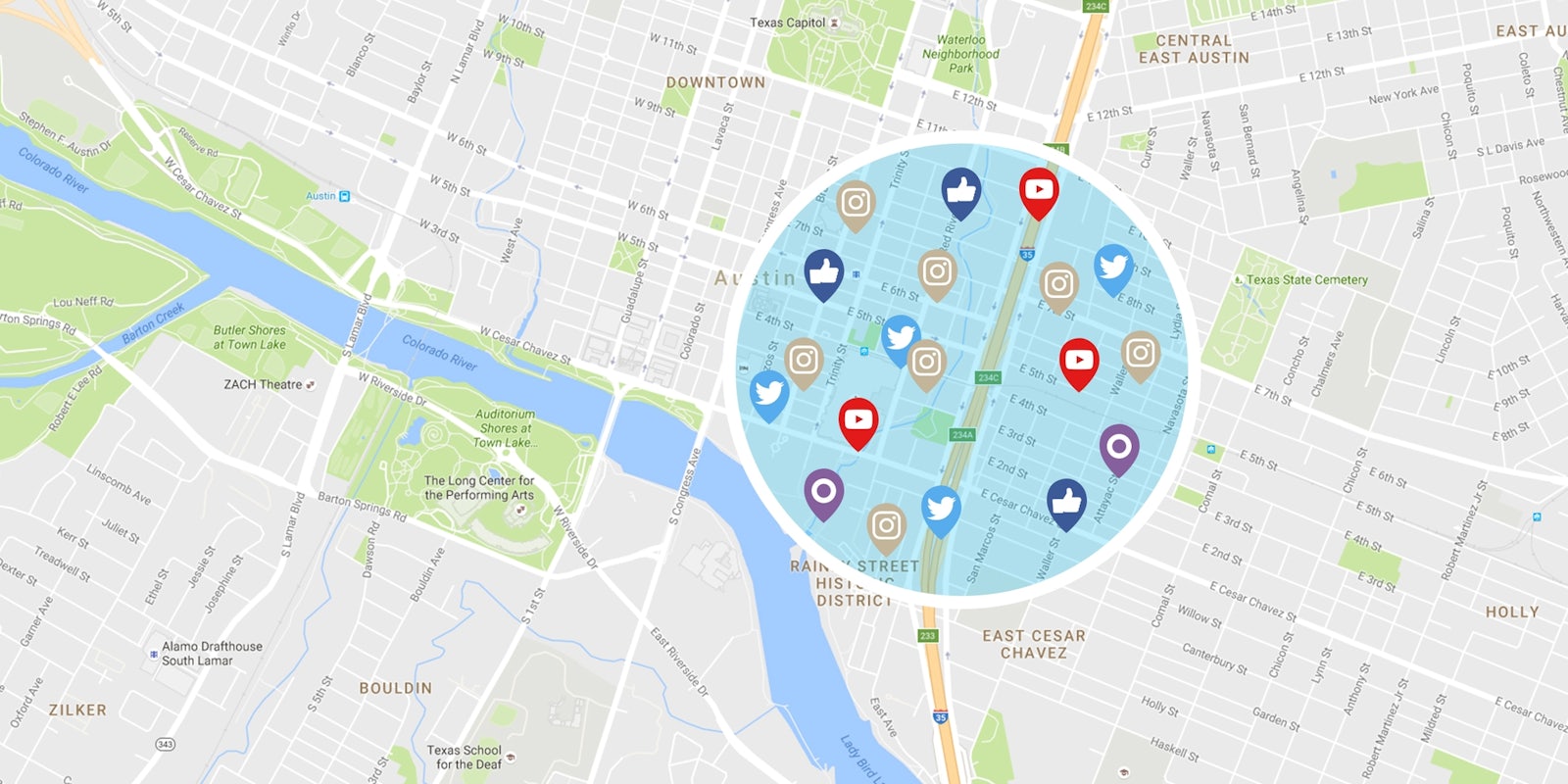

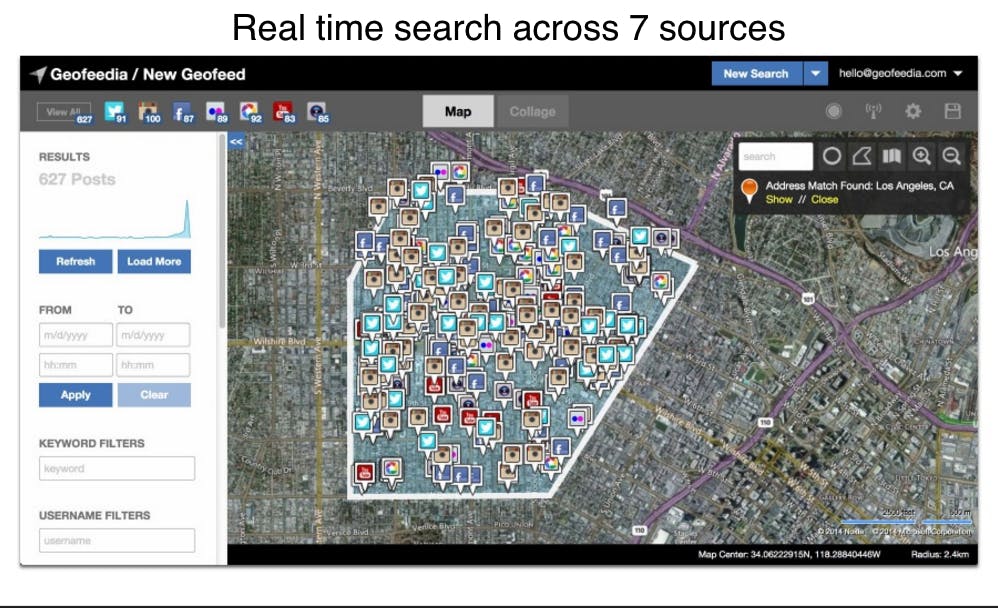

An analyst with the Sacramento Police Department in California said in an email that they purchased Geofeedia mainly because the cost was only $6,000 a year, as opposed to Snaptrends, which asked for $60,000. “We put a geofence around our whole city, so it’s recording the whole city 24/7,” the officer said in a July 2014 exchange. “We broke those fences down by District for easy of querying. We find that getting alerts for keywords is a very useful tool.”

Describing how the Geofeedia was being used, the Sacramento analyst said, “We have interrupted large parties, snagged guys with assault weapons and drugs, and intervened with a girl that was talking about suicide.”

Below is a brochure for Geofeedia provided to the Durham Police Department in August 2015:

Update 4:49pm CT, Oct. 11: A Twitter source has refuted Snaptrends’ promise of exclusive backend access to the social network’s system.