Opinion

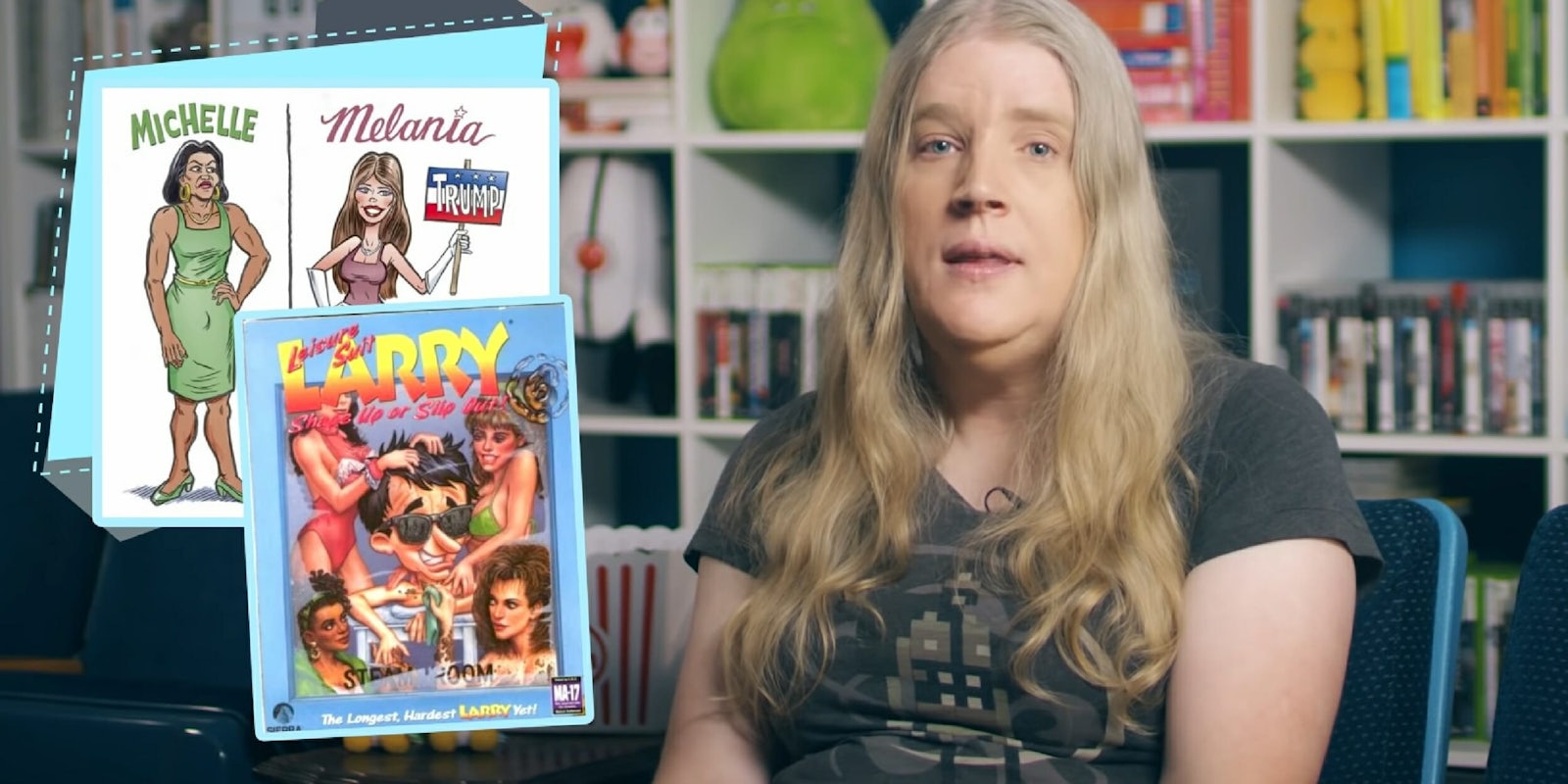

Poison is one of my favorite video game characters. She’s complicated and messy. She’s also ridiculously cool. The Street Fighter wrestler is tough, buff, and openly struts her stuff. She has quite the domme vibe going on, complete with a black cap, a leather collar, handcuffs latched onto her denim shorts, and a chain for a belt.

Sure, Poison is incredibly objectified, but what trans woman out there doesn’t want to be a buff fighter that can bring the greatest men in the world to their knees? She’s my problematic fave for a reason. I even have a commissioned art piece of her hanging on my bedroom wall.

Poison was originally introduced in Capcom’s 1989 arcade game Final Fight as an in-game enemy. Concept art from the game’s development describes Poison as a “newhalf,” a derogatory Japanese slang term for a trans woman. While fans have long debated her trans status over the years, and Capcom has never given an official stance on the matter, most consider Poison a canon transgender character. Street Fighter IV’s producer Yoshinori Ono cemented the idea in 2007, where he claimed Poison “is officially a post-op transsexual” in North America, and that “in Japan, she simply tucks her business away in order to look like a girl,” according to Kotaku. (Four years later, he’d walk back the claim in Electronic Gaming Monthly, saying there’s no canonical stance.) For what it’s worth, Capcom generally treats her with a fair amount of respect, with the series consistently gendering her as a woman and characters treating her as such.

But I don’t expect most games critics to understand the strange intersection where Poison sits for us trans women. But if there’s one YouTube channel that could do the job well, that would be Feminist Frequency. At least, that’s my impression after watching the organization’s latest series about queer tropes in video games.

🕹️🕹️🕹️

Over half a decade ago, Anita Sarkeesian debuted Feminist Frequency’s “Tropes vs Women in Video Games” on YouTube. Practically every woman in games journalism remembers the initial backlash against Sarkeesian’s work; for a time, simply mentioning the words “Anita Sarkeesian” would spark outrage on message boards, Facebook walls, and Reddit comment sections. Most criticism levied against Sarkeesian was in bad faith, with tone-deaf responses like “men die in video games too” and “not all damsels in distress are women.” It was an awful time to be a woman in games, doubly so for Sarkeesian.

And yet, Sarkeesian’s video series felt like a fresh breath for all of us. The videos looked at an enormous series of tropes in video games that female games critics had long noticed but were rarely given the space to talk about. One video, “Ms. Male Character,” looked at games where women are forced into normative feminine gender presentations to differentiate them from men. Another, “Women as Background Decoration,” analyzed objectification in gaming and how women’s bodies are used as sexual window dressing for male players. It’s safe to say the series influenced a generation of women in games criticism. I still think about the videos all the time when I write about games.

“Tropes vs Women in Video Games” was informative and fascinating for its time, but the series had its problems, and marginalized feminists, in particular, criticized the series for missing the mark on multiple occasions. Trans issues largely came up as an afterthought, Sarkeesian’s “Women as Background Decoration” videos were panned by sex workers for conflating sex work with objectification, and some of the examples used by the original series were heavy-handed at best. Those first few videos were a good start, but there was a lot of work to do to make truly intersectional and feminist games criticism.

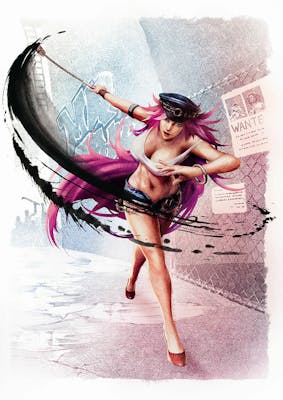

Six years later, Feminist Frequency has done that work. This week, the not-for-profit organization debuted “Queer Tropes in Video Games,” sharing three videos narrated and co-written by Feminist Frequency’s managing editor Carolyn Petit. In comparison to those original videos published by Feminist Frequency, Petit, Sarkeesian, and co-writer Christopher Persuad aren’t afraid to dive into the nuances behind queer characters in games. Each video tackles a different trope by exploring their affirming, negative, and neutral depictions in games, what’s already been accomplished, and where there’s room for growth. There’s a lot going on, and queer viewers are likely to find themselves nodding along throughout all three parts.

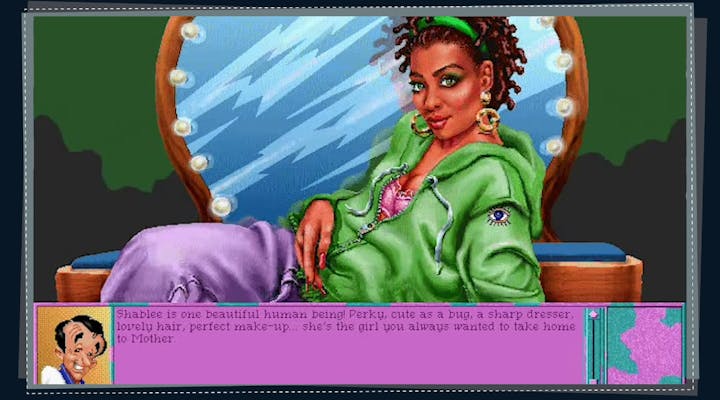

During “Press B to Hate Gay People,” Petit breaks down Leisure Suit Larry 6: Shape Up or Slip Out!‘s Shablee, a Black transgender woman whom the main character, Larry Laffer, meets in the game. Petit doesn’t mince words here with Shablee’s characterization, which falls into transmisogynoir, or transmisogyny levied against Black trans women.

For one, Petit points out how the game describes Shablee with incredibly racist language, following a scene in which Shablee reveals herself to be transgender through an enormous erection in her dress. This shocks Larry, who pukes in front of her. While he’s down on the ground, Shablee subsequently rapes him, which the game depicts as humorous. As Petit points out, the scene is incredibly disgusting: It mocks male sexual assault victims, it makes cisnormative assumptions about trans bodies, and worst of all, it depicts Black trans women as predatory men who secretly want to rape white men. Petit unpacks all of these problems with grace, and she even uses it as a segue into a much larger discussion on both transmisogynoir tropes’ impact on Black trans women and how the Grand Theft Auto series continues to punch down on trans women.

Petit isn’t afraid to point out when a video game simultaneously gets something right while doing something wrong, too. In the same video, Petit discusses The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild‘sVilia, who is coded by the game as a transgender woman. Link buys feminine clothes from Vilia, which Petit acknowledges, explaining how many queer and transgender fans have used Link’s outfit in order to headcanon—or interpret without canonically evidence—that Link is a transgender woman. While this stance is empowering for some, Petit points out that Breath of the Wild ridicules Vilia by showing other characters misgender her and exposes her facial hair as a gag. Like Poison, Vilia and Breath of the Wild are messy games, and Petit isn’t afraid to explain why.

That’s because Petit is an out and open trans woman in games journalism, one with an incredibly lengthy resume that spans from GameSpot to Vice’s Waypoint. By putting Petit front and center on Queer Tropes in Video Games, Sarkeesian is letting queer and trans folks lead the way with their own discussions on their representation in games. It’s a great message, one that shows Feminist Frequency is listening to feedback and embracing intersectionality as it moves forward.

🕹️🕹️🕹️

When Feminist Frequency first dipped its toe into gaming, the queer and trans indie games scene was just taking off. Twine, a popular interactive fiction medium, sparked a wave of bedroom queer and trans game developers making their own work DIY work. Many of their games weren’t just heavily narrative-driven, they refused to exist for pleasure or fun. These developers knew games could be sad, painful, affirming, loving, or just weird art things made for their own sake. While simple and straightforward, their queerness was undeniable, and they filled a void many of us longed for but never knew we needed.

That was half a decade ago, and the queer games world looks very different in 2019. Twine gave birth to games like Butterfly Soup and Life Is Strange, which explore queer coming-of-age experiences in ways that make their LGBTQ characters’ sexuality and gender feel center to the story, not adjacent to it. Then there are games like MidBoss’ 2064: Read Only Memories and One Night, Hot Springs, which fundamentally explore queerness through their games; they are literally built for gay and trans players. We even have a booming queer adult games scene now, with works like Christine Love’s queer BDSM visual novel Ladykiller in a Bind and Fortunae Virgo’s Hardcoded, the latter of which combines cyberpunk aesthetics with incredibly affirming (and hot!) trans bodies.

These works aren’t just sophisticated, they’re inspiring new developers to take up the mantle and share their own queer stories. After playing Nadia Nova’s queer trans games, I decided to create my own kinetic erotica Twine featuring a queer trans cult, a trans succubus domme, and a subby college trans girl. If my initial betareaders’ comments are anything to go off of, the game is coming along great. But as an erotica games writer, I stand on the shoulders of giants. I wouldn’t be able to make my Twine if it wasn’t for the queer devs who came before me and showed me that queer women want to play games about themselves.

When I first discovered Poison, I gravitated to her because she was one of the only trans characters around in gaming. But six years later, I don’t need to rely on Poison anymore to feel seen, nor does any other queer or trans person. We’re here, we’re out, and we’re developing the games we want to play. Series like “Queer Tropes in Video Games” are only strengthening our voices by fostering the kind of analysis that will inspire others to speak out and create games, too. That’s powerful, and for Feminist Frequency, it’s a sign of good things to come.