Opinion

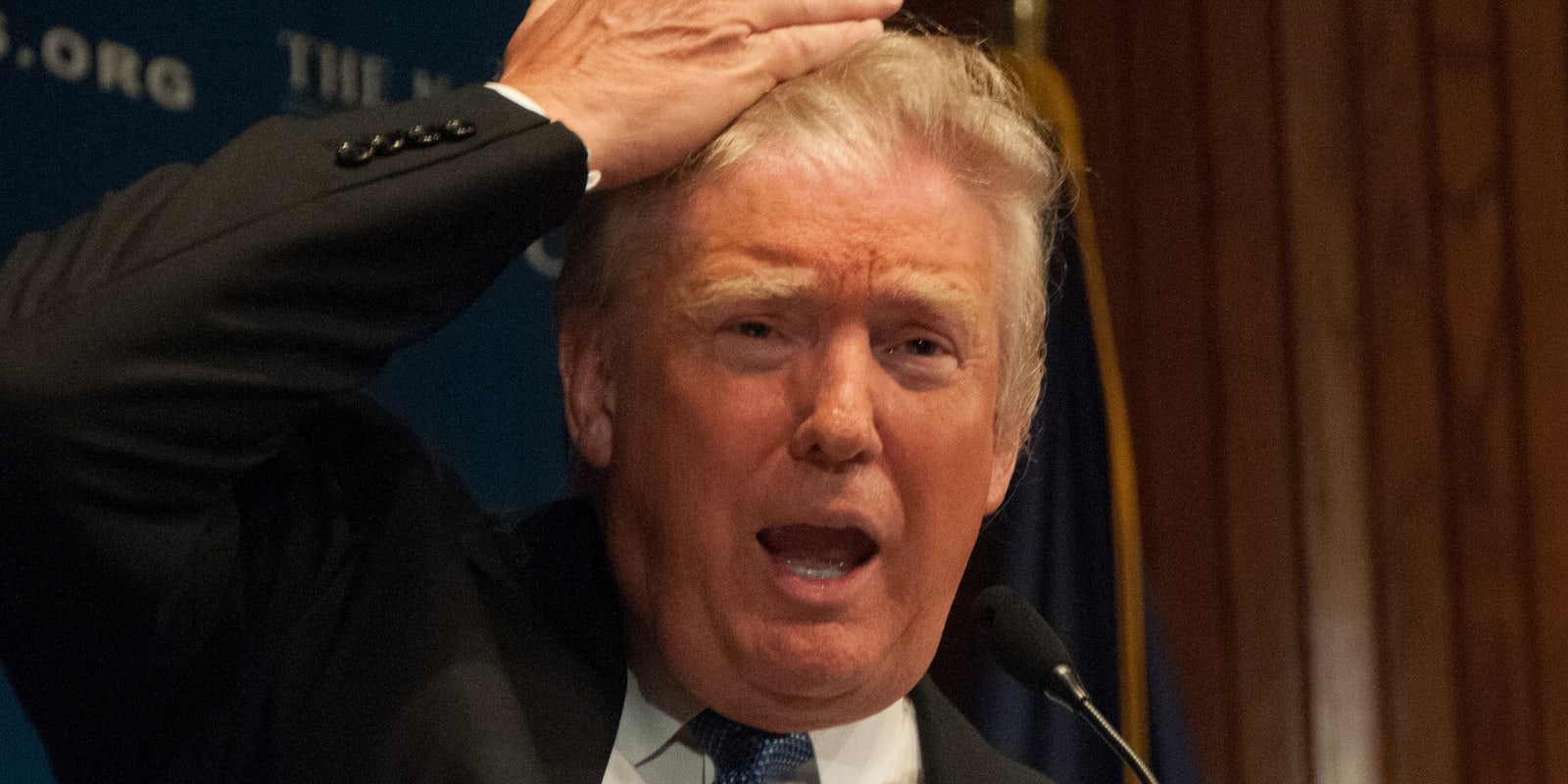

What kind of president would derail his first televised interview following the election to debate the validity of a race he won? This is what people were asking when Donald Trump sat down with David Muir of ABC News last week and could not let go of the fact that he won the Electoral College but lost the popular vote by 2.9 million ballots.

The 45th president claimed, as he has many times, that he would have won the election if not for “the millions of illegal votes” cast on Election Day, even though those assertions have been repeatedly proven false. “Of those votes cast, none of them come to me,” the president said. “When you look at the people who are registered: dead, illegal, and [people who voted] in two states, and some cases maybe three states, we have a lot to look into.”

That interview, and his proclivity for revising history, reignited long-standing speculation about Trump’s cognitive state—namely that he has a serious mental illness. Comedian Billy Eichner, the host of Fuse’s Billy on the Street, tweeted: “Well, this is completely insane. Not ‘insane’ in the casual way. Legitimately crazy.”

Keith Olbermann, now a digital correspondent for GQ, has been making this same argument on Twitter for weeks, opining that Trump should be disqualified from political office due to a serious psychological condition.

Armchair analysis of Trump’s state of mind became a meme last year following features in Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post that cautiously diagnosed the political aspirant as suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder. At a layman’s glance, the label more than fits. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, those diagnosed with the disorder exhibit symptoms that appear to characterize Trump’s boorish, outlandish behavior, including but not limited to: 1) a lack of empathy for others, 2) a “sense of entitlement,” 3) “arrogant, haughty” behavior, and 4) a need for “excessive admiration.” What about that doesn’t sound like Trump?

The speculation might be tempting, but it’s both morally unsound and extremely unhelpful in analyzing the real problems with Trump’s rise to power. The current president is not a product of disordered thinking but the normalization of misogyny and toxic masculinity—the very forces that helped put him in the White House.

Last year, the American Psychiatric Association put out a statement in response to the deluge of hot takes, calling speculation about Trump’s mental health “unethical” and “irresponsible.” Its criticism was based in what’s known as the “Goldwater Rule.” During the 1964 presidential campaign, Fast magazine polled 12,000 Freudian analysts across the U.S., who professed that Republican Barry Goldwater was mentally unfit to hold the nation’s highest office. Goldwater, who supported total military intervention to eliminate Communism, is most widely remembered for the “Daisy” attack ad, in which his opponent, Lyndon B. Johnson, suggested Goldwater would be responsible for nuclear war.

As a result, Goldwater lost the election in a landslide—winning just six states in total—but he successfully sued the magazine in court, winning $75,000 in libel damages. That case led to widespread reforms in how psychiatrists are allowed to ethically diagnose public or private persons. The rule of thumb is that in order to provide one’s professional opinion an individual’s mental state, said individual must be the physician’s patient.

“The current president is not a product of disordered thinking but the normalization of misogyny and toxic masculinity, the very forces that helped put him in the White House.”

Without a portal into Trump’s brain, we don’t know how Trump thinks—but what we do know what he does. Since announcing his run for president in 2015, the Republican has attacked and derided any woman who dared to criticize him. He called Clinton’s need to use the bathroom during a debate “disgusting.” Trump mocked the appearance of both Arianna Huffington and Carly Fiorina. He blamed debate moderator Megyn Kelly’s questions about his history of calling women he disagrees with “pigs” and “fat slobs” on her period. He continued to lash out at the former Fox News host on Twitter, calling Kelly “unprofessional” and “overrated.” The president most recently made similar comments about Meryl Streep.

This is not merely bullying. It’s indicative of Trump’s alleged predatory history with women. After tapes leaked of him bragging about grabbing women “by the pussy” to Access Hollywood host Billy Bush, at least 14 women have claimed that the billionaire groped them, sexually harassed them, or assaulted them—including a 14-year-old girl who says that Trump raped her at the apartment of Jeffrey Epstein, a convicted pedophile. Trump has dismissed these allegations and went on to say that several women were too unattractive to harass. “Believe me, she would not be my first choice,” he said of a woman who accused Trump of molesting her on an airplane.

Are these actions and words the product of a deranged mind? Not any more so than sexually assaulting a 13-year-old girl made Roman Polanski insane. The Chinatown director pled guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse in 1977 after drugging and raping Samantha Gailey, a teenage girl whose mother he met at a party. Polanski told the girl that the two would be taking pictures together for a photoshoot in a magazine, and Gailey imagined that she would be featured in Vogue Paris. Instead, he took her to Jack Nicholson’s home in the Hollywood Hills where he fed her Quaaludes and sodomized her.

What happened to Gailey had nothing to do with mental illness; in fact, the court declared Polanski competent to stand trial after a psychiatric evaluation. What drives a rapist is power, the feeling that he has the unique ability to violate women’s bodies without consequence. After all, Polanski is a beloved Hollywood auteur, one who continues to win Academy Awards even after fleeing his crime.

Men who abuse, harass, and target women for violence are rarely shy about their motives. Elliot Rodger, who killed two female college students on the University of California, Santa Barbara campus in 2014, claimed in a YouTube video that his act was designed to punish the women who refused to sleep with him and the men they jilted him for. “I don’t know why you girls aren’t attracted to me,” he said. “It’s an injustice, a crime because I don’t know what you don’t see in me, I’m the perfect guy and yet you throw yourselves at all these obnoxious men instead of me, the supreme gentleman. I will punish all of you for it.”

Entitlement is the through-line here. Rodger killed women because he believed he deserved them. Polanski lives in exile in Europe because, as a member of the Hollywood elite, he felt the rules of justice didn’t apply to him. Trump, meanwhile, actually told Bush why he continually violated women’s consent: “When you’re a celebrity, they let you do it,” Trump remarked on the tape. “You can do anything.”

Those comments might not say much about Trump’s mental health, but they do say a great deal about how he has governed thus far. The president spent his first week in office signing executive orders to strike at the basic rights of those less wealthy and powerful than he is. That includes banning travel from seven Muslim countries, including Syria, Iraq, and Iran, and vowing to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which has allowed millions of Americans to register for health insurance plans for the first time. When you’re president, one might say, they let you do it.

The son of a multi-millionaire, Trump grew up believing that the world was his for the taking, whether it’s manhandling the woman with the long legs across the room or occupying the highest office in the country, despite having few qualifications for the position. If Trump keeps insisting that he won the popular vote, it’s because he believes he deserved to.

That’s not derangement. That’s privilege.