For every major religion, giving to the poor is a fundamental pillar. And yet it seems like technology, rather than church, is augmenting charitable giving these days.

When a religious friend of mine was hospitalized for a fungal pneumonia in June, a loved one set up a crowdfunding campaign to pay for her medical bills. She said that while her faith is unwavering, whenever she needs help, the people at her church are the last people who come to her aid. “I think,” she said, “they just don’t know. I don’t think people understand each other’s lives like they used to.”

After another churchgoing friend experienced a stillbirth, a crowdfunding page was set up to pay for the burial. “I love my church community, but so much of my help comes from my whole community—friends and family—and they are all spread out,” she said. “And I think good can come from anywhere, not just church.”

Cullen’s family raised $30k to help him see the world for the first time. #gfmcheck https://t.co/U5MfkxGuNf pic.twitter.com/RvQzTzZjWo

— GoFundMe (@gofundme) July 29, 2016

In just 2 weeks, the Tampa community raised enough to get this family off the streets & put a roof over their heads. https://t.co/WvMsvtBaLC

— GoFundMe (@gofundme) July 28, 2016

But there was a time, not too long ago, before the internet and the reach of social media, when there were just churches and community centers. Where fundraising spaghetti dinners were hosted, and where bossy ladies whipped up casseroles for funerals and baby showers. The personal and the tragic were to be shouldered by your parish, your congregation, your groups for Bible study. These acts of kindness may still exist, but, as my friends point out, their days are waning.

Evelyn Birkby, author and longtime newspaper columnist for an Iowa newspaper, told me how the once-vibrant church community in her rural town of Sydney has been depleted and replaced by the growth of large urban churches and internet communities. For Birkby, who was born in 1919, the loss of the church at the hands of the internet’s wide reach is a tragedy.

“I go months without seeing my neighbors,” Birkby said. “I have no idea what their needs are and what their lives are like.”

Robert Putnam in his book American Grace argues that the modern church has lost sight of its goal of helping the poor. He told the Washington Post in a 2015 interview, “The obvious fact is that over the last 30 years, most organized religion has focused on issues regarding sexual morality, such as abortion, gay marriage, all of those. I’m not saying if that’s good or bad, but that’s what they’ve been using all their resources for. This is the most obvious point in the world. It’s been entirely focused on issues of homosexuality and contraception and not at all focused on issues of poverty.”

Additionally, church attendance is diminishing, and with that, giving to churches has declined. A 2014 study by Giving USA Foundation and the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy found that Americans give more to directly charity than to churches. And it makes sense, as charity is often not a top priority for churches who have to pay pastor salaries and operation costs, before they give to the poor or those in need.

For Birkby, this is a missed opportunity. “What is the church, if it isn’t to help people?” she asked.

“For the last 30 years, organized religion has been entirely focused on issues of homosexuality and contraception, and not at all focused on issues of poverty.”

But for those helped by crowdfunding, the internet can sometimes create a larger community than real life can provide.

Kaya Oakes, author of The Nones Are Alright, a book on millennials and religion, believes that crowdfunding campaigns are a positive development, because they are able to reach beyond the stereotypes that often plague churches and communities.

“Strangers can be emotionally moved by a crowdfunding campaign for someone they don’t know, whereas a sick person may be embarrassed to go to their family because families and friend networks are emotionally loaded with personal history,” says Oakes. “If you saw someone you knew on the street begging for money, for example, wouldn’t you be so shocked you might turn around? Whereas a homeless person you don’t know is anonymous and perhaps doesn’t come with emotional baggage in the same way. I think our human instinct is to help people, but it can be exhausting to constantly help our own families and friends out. Helping a stranger feels somewhat refreshing in contrast, because we can also do it anonymously.”

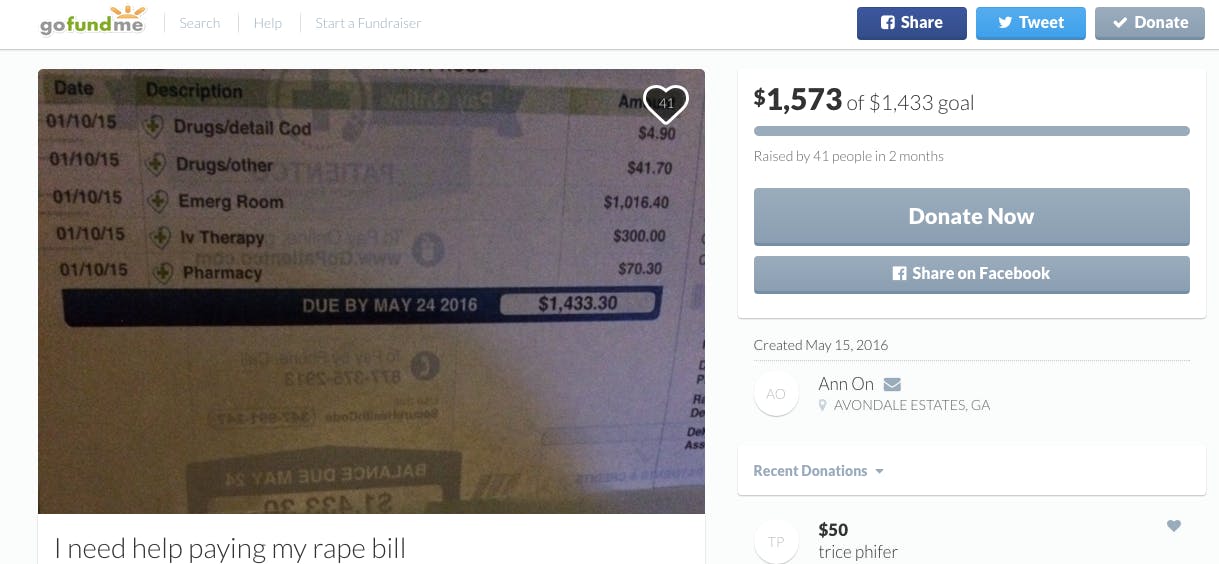

She also points out that when it comes to a person’s needs for help with a rape or an abortion, traditional forms of charity aren’t often an option. “In the case of sensitive issues like rape or abortion, no, I can’t imagine many would feel comfortable going to a church for help. Most religious organizations wouldn’t publicly support someone in that situation—even if it was, for example, a woman who’d been raped seeking an abortion. And that’s where community funding can feel safer.”

Bobby Whithorne, spokesperson for GoFundMe, a popular crowdfunding platform, sees his site’s model as augmenting, not superseding, traditional forms of community fundraising. “GoFundMe is not a replacement of community support, but just another way of expressing it.”

Because of its relative newness, crowdfunding is still a small, but growing, percentage of American’s charitable giving. A recent Pew study found that 22 percent of Americans have ever given to a crowdfunding campaign (compared to a Gallup Poll that estimated 83 percent of Americans have donated money to charity in general), with 36 percent of Americans still never having heard of sites like GoFundMe. And though some campaigns have the capacity to go viral, Whithorne notes that the majority of support for a crowdfunding page comes from people who know the individuals and are familiar with the situation.

Yet as Americans continue to become more internet savvy in their charitable giving, the support for crowdfunding campaigns is expected to rise. And this, Oakes notes, is a good thing. She says she sees potential for churches and communities to embrace all forms of charity to further strengthen the communities and relationships that support us in our time of need.

However, she notes that integration will likely be slow. “Christian churches in particular are notoriously bad about adapting to technology and social media—is your church on Twitter or Facebook and if so, do they update more than once a year?” Oakes says. “Not many do. But the alternatives like handing out flyers or standing with picket signs don’t always work as well as technology does.”

Whithorne also has hope for the future, noting that for every story of pain he reads on GoFundMe, “there are many more people who are willing to support and help,” and that, he says, gives him faith.