In April, 17-year-old Ta’Jae Warner was jumped and beaten to death while walking with her 11-year-old brother to the store in the daylight-filled streets of Brooklyn. More recently, in Delaware, 16-year-old Amy Joyner sustained a head injury that claimed her life after a high-school bathroom brawl that was supposedly over a boy.

While these two cases ended in worst-case scenarios, where victims lost their lives to violence, tons of other stories of black girls brutally beating other black girls have gone viral after videos of the attacks spread like wildfire online.

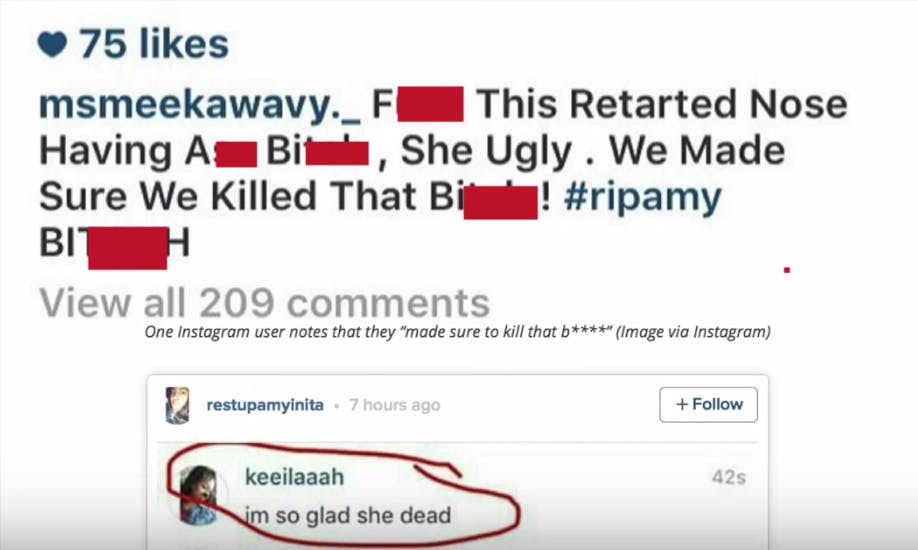

In Joyner’s case, the girls involved in her death immediately took to social media to brag.

Another even outlined the gruesome details of Amy’s death, saying she and two other girls “stabbed her with pencils” and “kicked her while she was down” on social media.The attacks were also video-recorded on cellphones by bystanders who did nothing but watch. Though the footage has been removed online due to pending investigations (one teen has been charged with homicide; the other two face misdemeanor conspiracy charges), a screenshot of Joyner’s struggle is still circulating on social media. It was taken just moments before losing her life.

This display of insensitivity shouldn’t come as a surprise to those who are familiar with such online fight videos. Hundreds of other fight videos featuring black girls have been uploaded into the digital world, capturing the deeply embedded violence found in parts of the black community.

Among the most popular websites that share these videos is the infamous WorldStarHipHop.com, where a search for the words “girl fight” renders 42 pages of results, most of which feature black girls fighting. MediaTakeOut is another enabler.

Requests for comment were sent to both WorldStarHipHop and MediaTakeOut as to why they allow and promote images of black violence. WorldStarHipHop did not return our request, and Fred Mwangaguhunga, founder and CEO of MediaTakeOut, which posted the screenshot taken moments before Joyner’s death, issued the following:

As the number once source for African American content within the web, we have an obligation to bring awareness & cover all issues that affect our community. Our hope is that by highlighting the consequences of these unfortunate events, we can encourage consciousness within our viewers. We should never have another tragedy like Amy’s again.

As of this posting, MediaTakeOut’s post titled “16-Year-Old DELAWARE High School Girl . . Is BEATEN TO DEATH By Gang Of Bullies . . . And They CAPTURED THE BEATING ON VIDEO!! (Shock PICS Inside)” is still up.

Yiasiah Lucas, a black woman raised in an urban environment who has witnessed plenty of intraracial violence between black girls, both on- and offline, explained the general appeal of these videos: “It’s entertainment and I feel like us, as human beings, we sort of like violence,” she told the Daily Dot. “I think we get a little pumped up when we see violence. I don’t think we want anyone to get hurt or killed—I don’t think it’s that extreme. But there is something about violence that intrigues humans.”

While it’s one thing to be a voyeur and not turn away when a video starts playing in your feed, it’s another to contribute. And it is also on social media where many of these conflicts spiral out of control, with bullying get worse online even before things turn violent in real time.

“We have had so many girls that literally had to leave school, because of Snapchat,” Tracie Berry-McGhee, a licensed therapist and founder of the nonprofit “SistaKeeper”—a mentoring wellness program that works with black girls— told the Daily Dot. “Whatever is written on there is gone in 24 hours, so it is impossible to monitor. So girls will say, ‘I wish you would die’ or ‘Go kill yourself,’ and then it is gone; there is no proof. They know nothing can be done.”

She further explained that Facebook and apps like Kik are used as unmonitored spaces where students embarrass one another and potentially instigate violence.

“Right now, there is something popular amongst teens called ‘Set out Sunday,’” Berry-McGhee said, where bullies set up victims under the premise of befriending them and then post mean things about them on Facebook for everyone to see. “For example, a girl can pretend to like another girl and ask to hang out with her at her house, but then she will use the public ‘Set out Sunday’ Facebook page to say her house was dirty, or some other degrading comment. So some of these kids are checking every week to see when it will be their turn to be bullied. You can only imagine how anxiety-inducing that would feel.”

Though adolescence is terrible, turbulent time for many kids, black children are much more likely to be both victims of and witnesses to violence than white children, according to the National Center for Victims of Crime. “Black youth are three times more likely to be victims of reported child abuse or neglect, three times more likely to be victims of robbery, and five times more likely to be victims of homicide,” according to the center’s site. “In fact, homicide is the leading cause of death among African-American youth ages 15 to 24.”

Yet, despite these alarming rates, black youth are still unlikely to find support from police or governmental institutions when threatened with violence, nor do they know where to turn or how to deal with the emotional and psychological impacts of such traumatization. “Ratting out” and seeking help is often stigmatized as a sign of weakness, and without encouragement or easy access to counseling, violence has a spiraling effect, sweeping young black children into a whirlwind of more violence.

The National Center for Victims of Crime initiative further explains:

Youth who are victimized during the complicated transitional period of adolescence may experience serious disruption of their developmental processes. These effects are worsened when youth perceive institutions as unwilling or unable to help or protect them, and adults’ failure to intercede confirms youth victims’ sense that they must cope with an unsafe environment by themselves and leads to delayed reporting and recovery for youth.

And to exacerbate these matters, black girls are faced with their own unique struggles that make it difficult to even begin to address the perpetuation of violence, both on- and offline. In media, positive black female role models are frequently overshadowed by the prevalence of angry/violent portrayals of black women who are quick-tempered and use fighting as a way to resolve conflict, especially in reality shows like the Love and Hip Hop franchise, The Real Housewives of Atlanta, and Love Thy Sister. We have become accustomed to not only seeing these angry images of black women, but to also being entertained by them.

“I think, number one, we have to look at our communities and our home environments where girls grow up not particularly caring or loving themselves,” Berry-McGhee said. “These young ladies are hurting, and when they look at television, radio, social media, they are not seeing positive images of themselves. They think reality television is true. And when you see African-American women throwing drinks at one another and calling them friends. … These girls are not watching age-appropriate television, and often times the parents are watching with them and validating what they see.”

“These young ladies are hurting, and when they look at television, radio, social media, they are not seeing positive images of themselves. They think reality television is true.”

And what these girls are watching in online spaces and on TV has grave impacts on their psychological and emotional development. A 2007 study in the Journal of Adolescent Health, called “The Impact of Electronic Media Violence: Scientific Theory and Research,” suggested that the short-term and long-term effects of exposure to media violence are disastrous. In the short-term, such violent media can prime subjects to display violence and also mimic what they watch. In the long-term, subjects can become desensitized to violent imagery, normalizing violence as a part of their fundamental understanding of the world.

Another factor that feeds this cycle of violence: racism, even at its most covert.

Kelly Wickham Hurst, a middle school guidance counselor, understands far too well the roles that cultural insensitivities and racism play in perpetuating black girl-on-girl assaults.

“There are very well-intentioned white people who work in the system who commit acts of racism every day,” she said. “In many schools, the bulk of the teachers are Caucasian and they don’t really know how to deal with black children or understand their backgrounds.

“I don’t think Brown v. Board of Education did us any favors,” she continued. “I think what it did was force us to go to school in white systems where no one there was forced to change—except to take us in as students.”

Berry-McGhee echoed this sentiment. She thinks many white teachers may need to be better trained to deal with the unique circumstances of black children.

“For example, there may be a girl who comes in and her hair covered—with a hood or a scarf or something—because it hasn’t been finished; maybe it is half-braided,” Berry-McGhee told the Daily Dot. “A teacher who has no cultural sensitivity, no experience dealing with this kind of situation, will demand the girl remove whatever is covering her hair, not thinking how much that may embarrass her. When the student refuses to remove the object, the teacher may possibly escalate the situation unnecessarily, and then when a fight breaks out, we will pretend the girl was just out of control.”

Furthermore, many members of the black community are afraid to address the rampant violence among young black girls out of fear that they will perpetuate stereotypes of black inferiority and savagery.

“It adds to the negative portrayal of black women in society,” Lucas explained. “If you look at the comments section on any videos where black girls are fighting, you will always see comments by white people like, ‘Look at them fighting like animals.’”

All of these factors together—the institutional failure to intervene when black children desperately need help or are exposed to violence, the cultural insensitivity of white teachers, and of course, the unmonitored online world that has become a space where young people can bully each other without fear of repercussion—have created a dangerous set of circumstances for black youth, and even more specifically for black girls.

To alleviate the way these violent videos are spread on social media, various petitions have cropped up online, including one on MoveOn.com to shut down the infamous WorldStarHipHop website. “Shut down the website World Star Hip Hop and ban similar websites which condone, accept submissions of, and feature ‘hood fight videos,’” its title reads.

“If you look at the comments section on any videos where black girls are fighting, you will always see comments by white people like, ‘Look at them fighting like animals.’”

Other petitions on Change.org called for both WorldStarHipHop and MediaTakeOut to stop sharing violent or hypersexualized videos. Most of these petitions didn’t garner the necessary support or signatures, except one that got WorldStarHipHop’s Facebook page removed for a while, only for it to pop up again. Other experts suggest that the accounts of those who forward and share social media violence should be deleted. But so far, there are no signs that such policies will ever be implemented.

For the black girls who continue to face the ramifications of a society laden with online and real-time violence, websites like Afro Puffs and Ponytails and SistaKeeper offer programs to empower, mentor, and inspire them to thrive. Cyberbullying.org also provides resources to parents, educators, and teens to better educate the public of the impacts of cyberbullying and to provide support for victims.

But this simply isn’t a matter of policing violence and tending to victims. It’s also about those with cellphones who are standing by idly, videoing as young black girls inflict potentially life-threatening blows on one another. And it’s about the rest of us, the faceless bystanders, giving clicks on Facebook and Twitter, too.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated for clarity.