More than 700 physical monuments honoring the Confederacy still stand in the United States. But the celebration and romanticization of our slaveholding ancestors is largely happening not over statues or at white supremacist rallies, but online. And mainstream genealogy sites and their users are partly to blame.

Genealogy and white supremacy have been linked in the United States since colonization, when wealthy families were obsessed with purity in bloodlines. In recent years, Americans have taken a renewed interest in discovering their lineage (some to prove that purity), heading to genealogy sites where the constructs of race and heritage—from family trees to DNA testing—are omnipresent. Without any historical context, though, what’s being compiled on sites like Ancestry.com is an alternative national history that relies on individual users to define how their ancestors are portrayed. That history conveniently leaves out millions of enslaved people.

Since around 2000, literally billions of birth and death certificates, U.S. Census records, military documents, family Bible notes, obituaries, and long-forgotten local histories have been uploaded to the internet, free to download. Ancestry.com, the wildly popular genealogy website that has allowed the mildly curious to trace their lineage back to Charlemagne, pulls most of its search results from the Mormons’ massive storehouse of historical documents in Utah, which is mostly searchable for free at FamilySearch.org. Ancestry members can also draw from any of the 70 million-plus public family trees that users have created on the site. In other words, most of these documented people are white.

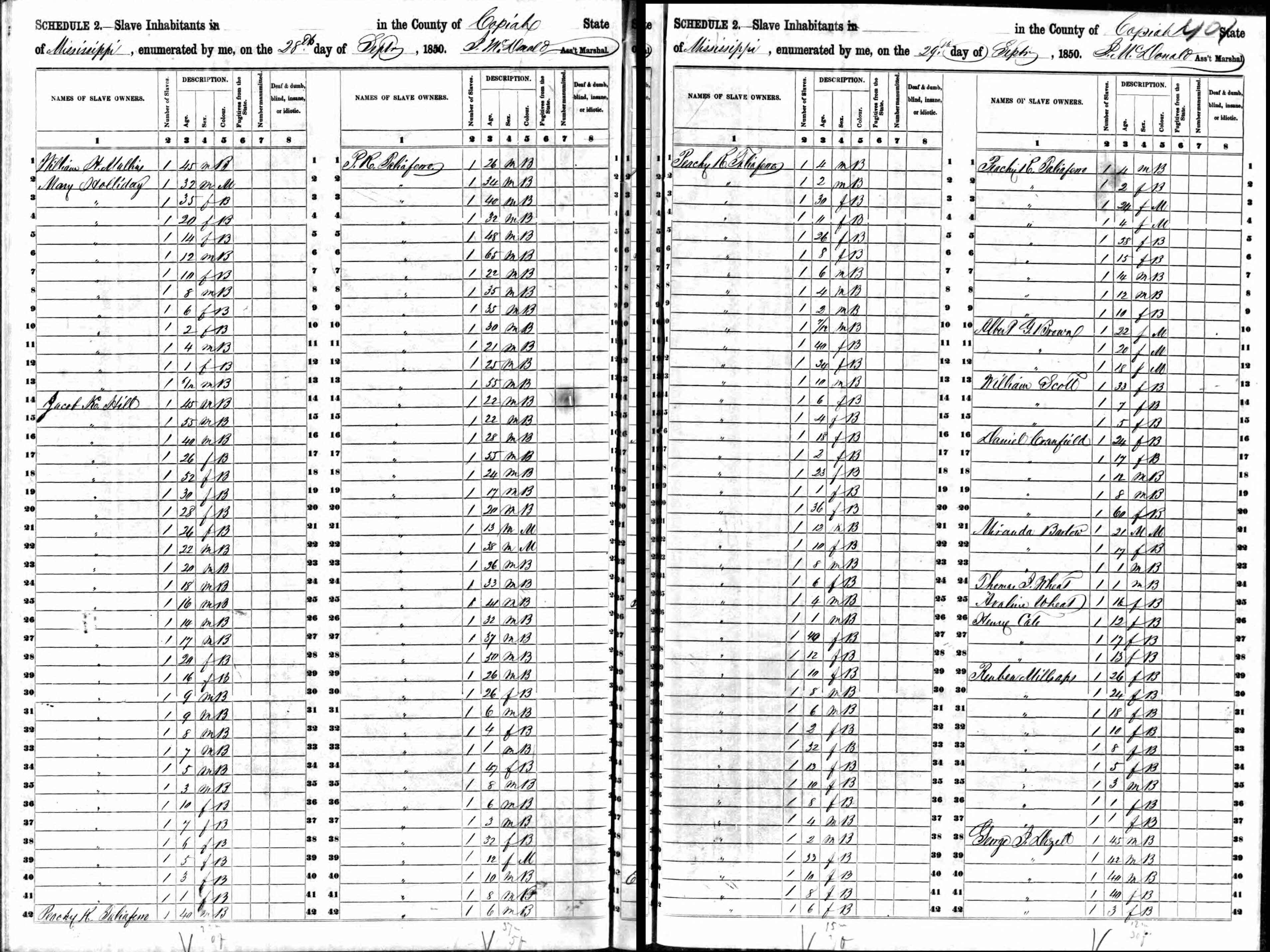

And yet it is hard to gather from reading these profiles that white people have any ties to owning slaves. Given that nearly one-third of Southern households owned slaves, Ancestry contains hundreds of thousands of profiles of slaveholders. The wealthier a person was, the more documentation there is likely to be about him or her, which means that slaveholder profiles should be repeated in millions of individual family trees.

However, you can only find a person’s slaveholding records if you search for them in Ancestry’s card catalog, or if you see them attached under the “sources” heading in another user’s family tree. And even when there is any mention of owning slaves, the details are often whitewashed by the inclusion of contemporary accounts or obituaries that paint the slaveholder as a righteous person. That profile then spreads and becomes the ancestor’s official digital record.

Find a Grave (which is owned by Ancestry) is worse. On this site, you can place digital “flowers” or other icons on graves, and leave anecdotes or warm remembrances for visitors to see. Profiles are tied to a picture of the individual’s actual gravestone or burial place, and a family tree function is built into the site. The tone is one of honor and nostalgia. There are exceptions, but there appears to be very little information about slavery or slaves on memorials to slaveholders on Find a Grave.

“Find a Grave is a platform for people to contribute burial information about their family, other people they have an interest in, or just as a service for the benefit of people who can’t come to the cemetery themselves,” a company spokesperson told the Daily Dot, “but we don’t actively curate the data or use it for education or other activities, though other people are certainly welcome to do that.”

Find a Grave does allow users to search memorials by “claim to fame.” Included in the lists are famous “Native Americans,” “Suffragists,” and even “Magicians.” Abolitionists and Civil Rights leaders don’t have their own categories, but can be found under “Social Reformers.” None of the browsable headings address slavery directly, although memorials for well-known enslaved people have been created by users on the site. For instance, Harriet Tubman’s Find a Grave memorial has more than 1,200 notes and remembrances, along with a lengthy biography that includes information about slavery. Other prominent Black abolitionists are similarly honored, with biographies that provide historical context.

Contrastingly, memorials to the perpetrators and protectors of slavery rarely address the subject of slavery at all. Confederate military officers are given loyal tributes on Find a Grave, decorated with hundreds of Confederate flag icons instead of digital flowers. The statue of Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard in New Orleans was removed in May after numerous protests, but his Find a Grave memorial features a glowing 1,200-word biography that manages to not include a single mention of slavery, and is accompanied by hundreds of Confederate flags and admiring notes added by visitors. (Find a Grave has suspended the “flowers” feature on some memorials to Confederates—including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis—because of “misuse,” although it is unclear specifically what kinds of comments illicit the suspension.)

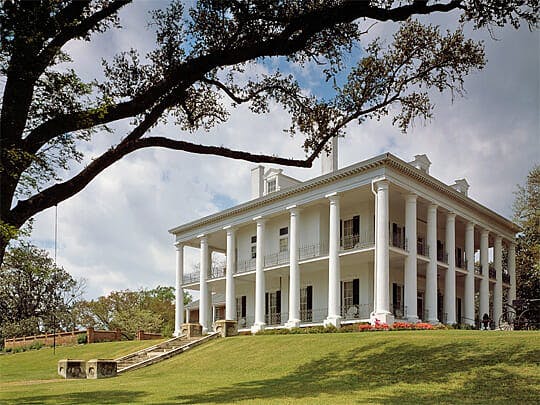

Portrayals of even the largest slaveholders in American history often lack any reference to slavery. Take, for example, Alfred Vidal Davis (1826-1899), whose number of slaves ranked him among the top 20 slaveholders in the United States in 1860. The son of a Philadelphia aristocrat and a Louisiana plantation heiress, Davis was born and raised in Louisiana. At age 34, Davis owned 637 slaves on multiple plantations in both his home state and Mississippi, including more than 100 children under the age of 7. Davis was wildly rich—a billionaire in today’s dollars—and was a prominent member of an interconnected group of elite slaveholders called “Natchez Nabobs.” According to An American Aristocracy by Daniel Kilbride, the Davises sometimes spent years at a time in Philadelphia and New York, spending lavishly to entertain their wealthy friends and business partners. Meanwhile, the overseers on their plantations generously applied the whip in order to increase cotton production, which doubled between 1820 and 1860.

It is unfortunately very easy to portray a major slaveholder as a prestigious, hard-working ancestor, with no reference to the generations of enslaved people who were crowded into cabins on his plantation. None of the public family trees with sources attached for Davis on Ancestry mentioned his owning slaves, in spite of the fact that one of his former slaves, John R. Lynch, became an important Reconstruction-era politician. Find a Grave has a nice memorial for Davis, which lists his family ties and a few flowers and pleasant messages. There is no mention whatsoever about the role he played in enslaving generations of people in the South.

Then there is John Harleston Read. Of the 393,975 slaveholders documented by the census in 1860, Read also ranked in the top 20, with 511 slaves. Born in 1815, Read was part of Charleston, South Carolina, aristocracy. According to historian Helen B. Trimpi’s 2010 book, Crimson Confederates: Harvard Men Who Fought for the South, Read was educated at Yale and Harvard, and served as a state representative from the mid-1840s until his death in 1866. Read and his family lived like royalty, sending his children to study in Europe and leaving the operation of his plantations to his overseers.

Read’s immense fortune came mostly from rice exports. Harvesting rice required living and working in swamps, where malnutrition and malaria were rampant, and cruel overseers gave no care or attention. For mothers forced to work in the rice fields, it was very likely their babies would die. According to the 1860 census for Georgetown County, the population included 3,013 whites, 183 “free colored” people, and 18,109 slaves. It was a slave society from the bottom to the top, and John Harleston Read, who went on to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War, was on top.

It took only a few hours to quickly research Read. Several academics have written about him and his family, including Christopher Dickey in Our Man in Charleston: Britain’s Secret Agent in the Civil War South. But after reviewing all of the public family trees that included Read, only about one out of 10 made any reference to his slaveholding history—in the form of posting a 1,200-page probate document that includes his will. Not one single public family tree listed the slave schedules (part of the U.S. Census) for Read, even though the documents exist on the site. Ancestry does not automatically attach records to profiles—it relies on users to search for them and attach them if they wish.

“There are several different ways to locate slave schedules,” the company spokesperson told the Daily Dot. “You can search in the card catalog, to find all databases on Ancestry that contain those records. If you think someone in your family tree might be a slaveholder in 1850 and/or 1860, you can also click the search button directly from their profile page and then filter your search results by Census.”

Unless a user decides to check if an ancestor owned slaves, the profile will not include that information. Without a doubt, some users do that research. But relying on white people to voluntarily tie their family heritage to the history of slavery has not produced accurate digital portraits so far.

Of course, African Americans searching for their family histories have also benefited from the availability of scanned records—including searchable documents on FamilySearch and Ancestry. Other sites like AfriGeneas and Our Black Ancestry offer records, research guidance, and forums to share information. Family records and stories, as well as slaveholder wills and probate documents, in combination with other historical research, can shed a light on the lives of individual enslaved people and their descendants. Slave schedules from 1850 are searchable for free at FamilySearch; 1860 slave schedules are only searchable on Ancestry. Based on the availability of these documents, numerous regional websites and blogs have been started by the descendants of slaves searching for their roots.

But verifying the identities of individual African-American ancestors before the 1870 Census can be extremely difficult because no names of slaves were recorded on Census documents before the Civil War. Researchers call this “the 1870 brick wall.”

Ancestry does, however, make an effort to post blog articles about how to search for African-American ancestors, along with videos on the subject. In addition, “Ancestry has digitized more than 20 historical books that address slavery directly and they are available by searching the card catalog on our site,” the company spokesperson said.

Then, of course, there is Ancestry’s marketing, which also often includes images of Black Americans to show that we are one big interconnected family. And while that is, in fact, true, years of institutionalized rape of enslaved women by white slaveholders and overseers is largely the reason—a fact that does not immediately come to mind in the warm glow of old photos and happy users.

So while white Americans happily share original documents from the 1700s with details about their individual ancestors, millions of enslaved people will remain forever nameless, untied to even a single family tree. You could say this is what white supremacy looks like—the glorifying of whiteness, the erasure of Black people.