Opinion

Janet Mock. Pose. Nevada. Chelsea Manning. Sex workers’ rights. The 2010s are coming to a close, and it’s been one hell of a decade for trans visibility. Just 10 years ago, trans people were barely gendered correctly in the mainstream news cycle; in 2019, we’re everywhere, demand respect, and are absolutely impossible to ignore.

The 2010s were a tumultuous time for trans people. On the one hand, we gained some of the strongest anti-discrimination protections in American history. But we also faced some of the biggest challenges, from a hostile White House signing SESTA-FOSTA into law to celebrities like J.K. Rowling and Graham Linehan attacking the trans community.

But most of all, the 2010s diversified what it means for a trans person to be trans. Our identities broadened, our self-image blossomed, and we became more aware of the various experiences trans people have within our community. Here are 10 of the most important way this decade expanded what it means to be trans—and what it means to achieve trans rights.

How the 2010s redefined what it means to be transgender

1) Queer games enter the public eye

In their book Video Games Have Always Been Queer, Bonnie Ruberg argues video games are fundamentally playful, experimental, and subversive in ways that can only be considered queer. Much like kink, which also has an enormous queer base, games let trans people play with systems and even subvert expectations of what it means to play a game. There’s no better example of that than the queer and trans developers who came into their own during the 2010s and ushered in new ways of thinking about trans experiences and what it means to play games.

Anna Anthropy’s exploration into gender transitioning Dys4ia is a stereotypical example, cited so often that it’s become a trope. Nadia Nova’s Twine games explore trans sapphic desire in both light-hearted and heartbreaking ways. Arielle Grimes’ BrokenFolx looks into the ways in which queer and trans people are forced to navigate a world unkind to their daily existence. Heaven Will Be Mine from Pillow Fight Games looks at queer trauma through dykes piloting sci-fi mechs. The strongest queer contender is Ghosthug Games’ cyberpunk visual novel Hardcoded, which explores trans lesbianism through a trans woman’s sexual relationships and flings with cis and trans women.

Many trans women, myself included, learned about their gender identity through queer games. And while some of the most influential queer indie games from the first half of the 2010s are no longer online—Dys4ia can only be found on certain Flash-supported websites—their rise and disappearance are a microcosm of queer art: fleeting, formative, and unforgettable.

2) The emergence of the trans journalist and critic

Digital media’s rise, alongside increased visibility for feminism and queer rights in mainstream culture, convinced editors to bring on writers and editors from marginalized identities. Trans journalism, personal essays, and editorials, in particular, boomed over the 2010s, and some of the biggest names in the contemporary trans media sphere got their start during this decade. Memorable figures include Freddy McConnell, Adryan Corcione, Carta Monir, Mey Rude, Harron Walker, Katelyn Burns, Meredith Talusan, Lucy Diavolo, Serena Sonoma, Kam Burns, and the Daily Dot’s Alex Dalbey-Thomas, among many others. Each of these writers diversified the media landscape, pushing the Overton window by demanding trans liberation from a society that insists being cisgender is the default. And thanks to their hard work, the 2020s will usher in a new generation of hard-hitting trans journalists who aren’t afraid to fight for our rights.

3) The rise of the transgender celebrity

Transgender public figures have existed for the longest time in mainstream culture. Just look at Andy Warhol superstar Candy Darling. But the trans celebrity as we know it today only came about during the 2010s. These celebrities embrace their transness on their own terms and are lauded for it, more often than not serving as inspirations for the community at large. They can also serve as advocates and voices for the unheard, or just be themselves publicly. Jazz Jennings of I Am Jazz, Yance Ford, Laura Jane Grace, Laverne Cox, Indya Moore, Daniel Mallory Ortberg-Lavery, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, Bailey Jay, Gigi Gorgeous, and, of course, Janet Mock are all such examples. Perhaps most famous (albeit controversial) of all is Caitlyn Jenner, who, while largely seen as out-of-touch compared to the rest of the trans community, helped usher in the “trans tipping point” with her coming out.

4) Sexual education for trans people emerges

Queer sexual resources are still few and far between, and that’s doubly the case for trans men, women, and nonbinary people. But this decade ushered in new conversations around trans bodies. Safe sex guides for trans men and women appeared. Trans men taught the world more about testosterone’s impact on their sexuality. Allison Moon’s Girl Sex 101 collected extensive information on sex with trans women, including how to touch our genitals in pleasurable (and sapphic!) ways. A significant amount of this information came directly from the trans community: Writers like Zinnia Jones, Mitch Kellaway, Mey Rude, Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, and Sam Riedel came onto the scene to teach the world more about trans bodies. Best known by far is Mira Bellwether’s Fucking Trans Women, introducing the world to sex with girls’ dicks and more. My column Trans/Sex debuted in 2018 as an opportunity to spread sexual knowledge about our community beyond coastal cities like New York and San Francisco. Over one year later, it’s still going strong.

There’s still a long road ahead. But trans bodies are being taken seriously in feminist book stores and sex shops. That’s a sign that our culture is starting to let us be sexual on our own terms, not on the terms of a cis dude who’s browsing Pornhub.

5) Trans fiction by and for trans women

Much like Dys4ia, Imogen Binnie’s Nevada has been written about to death. It is the trans literature book, and I wrote about it early in my transition. But there’s a good reason why so many millennial trans women adore Nevada: For many, it was the first book with characters just like them.

That’s not to say Nevada is the best work of trans fiction ever. The book’s story is haphazard and very much rooted in a white, middle-class, Brooklyn transplant’s perspective. But in its wake followed dozens upon dozens of works that not just eclipsed Nevada in terms of prose but brought with them an enormous range of lived trans experiences. Casey Plett’s A Safe Girl to Love and Little Fish follow the woes and hardships of trans adulthood. Torrey Peters’ Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones merges trans womanhood with sci-fi social commentary. Kai Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars looks at trans sex workers of color in a way that’s not just reflective of the myriad identities within trans womanhood and pushes back against Nevada’s anxiety around sex work and whiteness. Meanwhile, Jamie Berrout’s short story collection Portland Diary explores all-too-realistic speculative fiction worlds where marginalized trans women of color fight for survival against powerful, white, capitalist institutions.

These writers let trans people realize that their stories are important, they deserve to be told, and the messy issues we deal with on a daily basis are important. It’s fiction by us and for us, unapologetically so.

READ MORE:

- In 2019, I learned why Pride isn’t Pride without kink

- How can we create more inclusive sex education offline?

- TERF wars: Why trans-exclusionary radical feminists have no place in feminism

- Ending violence against trans people starts with respecting them in everyday life

6) Nonbinary awareness increases, celebrities come out

As discussions on binary trans rights continue to enter mainstream media (for better or worse), one important umbrella remains extremely marginalized: nonbinary identities. Even within the trans community, many binary trans men and trans women belittle nonbinary rights, joke about genderqueer people, or suggest trans people who do not experience gender dysphoria aren’t “really trans.”

There’s still a lot of work to do for nonbinary rights. But over the 2010s, we started seeing real change thanks in part to increased visibility. Musician Sam Smith, Queer Eye’s Jonathan Van Ness, Pose’s Indya Moore, The Hate U Give’s Amandla Stenberg, and Steven Universe’s Rebecca Sugar all came out as nonbinary this decade. Others, such as trans theorist Kate Bornstein and writer Meg-John Barker, have received renewed focus.

The Daily Dot’s reporter Alex Dalbey-Thomas is nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns. They first learned about nonbinary gender identities through an LGBTQ studies class in 2012; two years later, they came out for the first time. They fully came out earlier this year and remain hopeful for the road ahead.

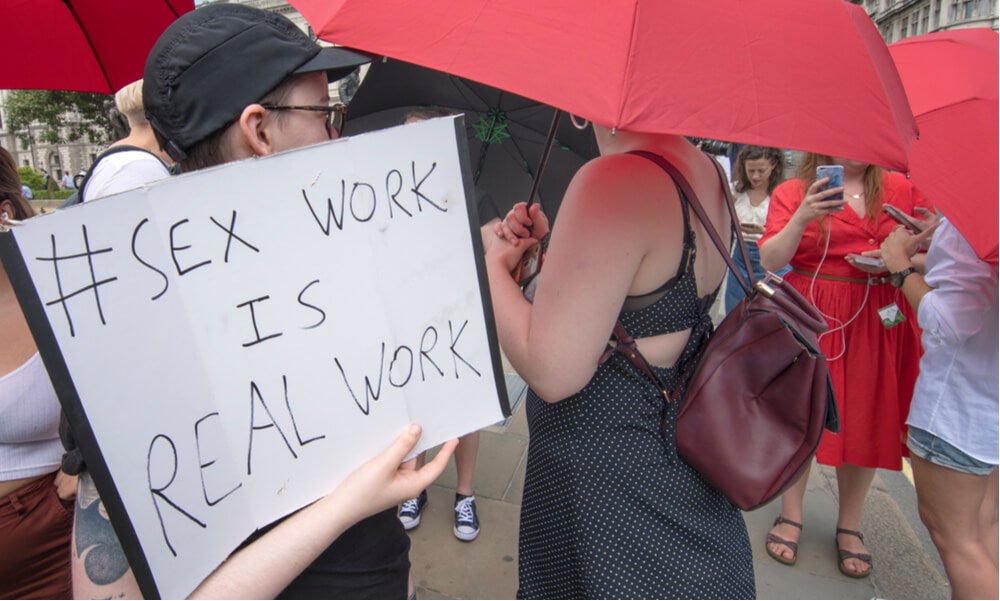

7) Sex workers’ rights discourse slowly enters the mainstream

By now, “sex work is work” is a well-recognized mantra in social justice spaces. But that didn’t happen overnight. The fight for sex workers’ rights has been a long, heartbreaking road throughout the 2010s, with just as many victories as defeats. Many trans people do or have done sex work, partially due to socioeconomic discrimination. A 2015 analysis of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey found over 10 percent of respondents have done sex work at some time in their lives. Black and multiracial Black participants make up nearly half of sex workers within the survey, followed by Latinx sex workers at one-third. This fight isn’t just about trans people and sex workers, it’s specifically about securing labor rights for the trans sex workers of color within our community.

While we haven’t exactly reached a tipping point yet for sex workers’ rights, fighting for decriminalization means fighting against predatory violence carried out by the police. And when we fight for sex workers’ rights, we must remember to listen to the queer, trans, survival sex workers of color in our lives first and foremost.

8) The fight for inclusion reaches public institutions

One of the first investigative stories I wrote was in 2014 for a local newspaper. The article, which was published under my old name, was about the first openly known transgender woman officially accepted into my university’s women’s college, as well as the school’s official policy confirming that trans women are allowed to join. I was excited to break the news, but now I realize my story was part of a much larger trend of trans people fighting for their rights on an institutional level.

Over the past decade, public schools, colleges, and sports programs have grappled with what to do with transgender people. This hasn’t always been inclusive. In-state legislatures across the U.S., bathroom bills and “debates” around trans discrimination became commonplace. President Donald Trump announced the so-called “trans military ban” preventing transgender Americans from enlisting. Some institutions are faster to accommodate trans people than others; a few are even moving backward. But there’s a silver lining: This decade taught trans people that they have a fundamental right to fight for spaces that align with their gender. Just 10 years ago, demanding that right was considered taboo at best. Now, it’s headline news.

9) Chelsea Manning’s coming out and short-lived freedom

In August 2013, Chelsea Manning came out as a transgender woman, requesting the media “refer to me by my new name and use the feminine pronoun.” American media grappled with Manning’s gender identity before finally coming to terms with the community’s best practices of using her preferred name and pronouns. Thanks to her fight for unconditional acceptance, Manning set the standard for accommodating media coverage of trans people over the decade. And her subsequent release under a commuted sentence was a pivotal moment for trans rights in the public eye. She was not just a celebrity, she was an anti-establishment figure who stood for trans liberation via radical resistance.

As of this article’s publication, Manning remains indefinitely jailed for refusing to testify to a grand jury, an act that could only come from someone with as much integrity as someone like Manning. In a world that’s still struggling with trans acceptance, Chelsea Manning is proof that trans resilience is possible despite all odds thrown our way.

10) The pressing need to center trans women of color

More than anything, the 2010s taught us that the trans community needs to do better. Many times, white trans men, women, and nonbinary peoples’ lives get the most visibility in mainstream culture while queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) are left out of the equation. This decade taught us that if we want trans rights, we have to do it collectively, and that means every step forward must center trans women of color.

Writer, editor, and activist Ashlee Marie Preston stood up to Caitlyn Jenner in 2017, calling out her support for Trump. Filmmaker Reina Gossett drew attention to the ways in which trans women of color’s vital community-rearing work is ripped from their hands and used by white people. Pose shined a light on the challenges trans women of color faced during the 1980s and ’90s, revealing how TV and film must make room for more than just self-serving, white-centric trans narratives. And Janet Mock and Laverne Cox emerged as powerful voices for Black trans women in particular.

For white trans writers such as myself, the past decade showed us we need to do better. We can and must center trans people of color in our work. And it’s on us to stop, listen, and actively seek out opportunities to help QTPOC every chance we get.

READ MORE: