Last week was a big one for Mars fans. First we discovered water, and then we rescued The Martian. NASA is already on a mission to reach the planet in our lifetime, and would-be space travelers are already planning ways to warm it up once we get there.

But the recent resurgence of interest in the red planet isn’t just down to images from the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers. If the annals of science fiction are any indication, humans have had their sights fixed on Mars for centuries.

“I suspect the current interest in Mars is due to both new information about the planet itself and new understandings of the complex human effort it will take to get there,” Professor Lisa Yaszek told the Daily Dot.

“Historically speaking,” Yaszek said, “popular interest in Mars has waxed and waned over the past 150 years in relation to new technologies that provide new perspectives on the planet.”

Yaszek teaches science fiction at Georgia Tech, which led the study revealed in last week’s Mars water discovery. We asked her about the history of space exploration on the red planet—along with the history of Martian invasions. Yaszek discussed how Andy Weir’s novel The Martian fits into this pattern—and how it stands out.

The history of “Mars invasion” stories has always seemed to be about exploring our fear of

the Other. The Martian, on the other hand, is about humanity exploring and colonizing a

world that’s essentially unthreatened by human ingenuity. Does this make it unique, or is it a

return to the kind of “new frontier” stories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

Yaszek: Science fiction authors have been telling stories about Mars since the inception of this

wildly popular genre in the nineteenth century. Such stories tend to fall into two broad

types: invasion stories such as H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds (1897) and adventure or

exploration stories such as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars stories (novelized as

A Princess of Mars in 1917).

Sometimes the two even come together, as in Garrett P.

Serviss’s Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), which is an unauthorized sequel to War of the

Worlds in which Thomas Edison leads an expedition to the red planet to obliterate the

Martians once and for all—and to claim Mars as the new American frontier!

As a story about exploration and colonization, The Martian clearly fits into the latter

category. But the fact that there are no Martian natives to grapple with in Weir’s book—just

a dangerous and potentially hostile landscape—suggests that his novel is actually closer in

spirit to the new generation of Martian colonization stories that sprung up in the 1950s and ’60s. Prior to this period, authors tended to skip over the details of how we might get to

Mars in favor of speculation about what kinds of life Mars might host. But by the middle of

the 20th century, early successes in the space race made interplanetary travel seem

like something that might happen soon, while new visual data suggested that Mars was

likely to be inhospitable to human life.

Accordingly, stories such as Arthur C. Clarke’s The

Sands of Mars (1951) and Isaac Asimov’s “The Martian Way” (1952) try to imagine in

practical terms what kind of effort it would take to colonize Mars and make it livable for

humans.

This period also sees the first stories about explorers who are stranded on the red

planet, including Lester Del Rey’s Marooned on Mars (1951) and James Blish’s Welcome to

Mars (1966). While most of these stories are more realistic and less romantic than their

turn of the century counterparts, they all share the same optimistic belief that brave men

and women can work together creatively and compassionately, using all the scientific and

technical knowledge available to them, to survive a hostile Martian landscape and even

claim the red planet for humankind. That optimism is very much at the heart of The

Martian.

Do you think this recent resurgence of interest in

Mars is due to advancing science and new understanding of the planet, or is it reflective of a

cultural shift? Or both?

I suspect the current interest in Mars is due to both new information about the planet

itself and new understandings of the complex human effort it will take to get there.

Historically speaking, popular interest in Mars has waxed and waned over the past 150

years in relation to new technologies that provide new perspectives on the planet. Mars

first became a popular setting for science fiction stories in the mid-to-late 1800s, when

telescopes revealed that the moon was inhospitable to human life, but suggested that there

might indeed be water, vegetation, and perhaps even the remnants of an ancient

civilization on Mars. As telescopes were refined and new data revealed that Mars was likely

to be very dry and cool with little atmosphere, authors shifted emphasis from stories about

invasion and exploration to the promises and perils of colonization.

Photos taken by the

Marnier probe in 1965 and the Viking probes in 1976 confirmed that Martian conditions

were so inhospitable to human life that science fiction authors became discouraged and

turned their attention elsewhere.

By the mid-1980s, however, scientists and politicians were ready to return to the

challenges of thinking about Martian colonization; indeed, in 1989 U.S. President George

Bush revealed a plan to put humans on Mars by 2019.

Meanwhile, new data from recent

missions including Pathfinder (1996), Rover (2003) and Phoenix (2007) bolstered hope

that there might still be water beneath the planet’s surface, which would make colonization

efforts somewhat simpler. And at that point, science fiction authors were ready to start

dreaming about Mars again, too!

What’s interesting about this period is that authors

resurrect all the old Martian story forms—the invasion tale, the Martian romance, the

colonization tale—but with a new appreciation for the beauty of the Martian landscape.

This leads to an explosion of stories about the promises and perils of terraforming, as in

Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy and Geoffrey Landis’s Mars Crossing (2000). Even

stories such as Rick Moody’s The Four Fingers of Death, which hearkens back to War of the

Worlds, can be seen as part of this new movement in its appreciation and celebration of

Martian microbial life.

A similar appreciation haunts Andy Weir’s The Martian as

well—even when it seems most likely to kill him, our hero manages to take a few moments

here and there to really appreciate the beauty of this world that seems determined to kill

him.

But new technoscientific information isn’t the only factor informing our new optimism

about the possibility of human life on Mars; instead, new understandings of the complex

efforts it will take to get there are important, too! Over the past two decades it has become

increasingly apparent that no individual country is likely to make it far into space on its

own, while joint efforts such as the International Space Station suggest that humans from

all nations can make great strides when they work together. Even with its limitations,

cross-country collaborations such as these are the stuff that science fiction dreams are

made of!

Ever since Garrett P. Serviss imagined that Thomas Edison would lead an

international crew to the red planet… science

fiction authors have dreamed of futures without borders. We see this again in the most

recent generation of science fiction stories about Mars and especially in The Martian,

where the fate of our nominally American hero hinges at several points on the decisions

made by non-Americans across the globe and in outer space. It’s a heartening story in an

age of very complex global politics.

For the newbie reader, what are some of the quintessential must-read/must-watch sci-fi related to Mars in your opinion?

There are so many great stories—and films, and comics, and video games—about Mars

that it’s hard to choose just a few! As a literary person, I can’t help but recommend mostly

stories. If the newbie reader hasn’t encountered Wells’ War of the Worlds (1897) yet, I’d

suggest beginning with that—and then reading Garrett P. Serviss’s very 19th-century

American response, Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898).

There is also an amazing great early

science fiction film set on the red planet, Soviet director Yakov Protazanov’s Aelita: Queen

of Mars (1924).

From the middle of the 20th century, when colonization stories first become popular,

I’d recommend anything by Robert Heinlein that takes place on Mars, but especially the

book Red Mars and the film Rocketship X-M.

I’d also recommend Ray Bradbury’s Martian

Chronicles because it provides a very different, very surreal take on the planet—it’s a

beautifully written set of stories!

And if the newbie was so inclined, I’d recommend hunting

down Detective Comics [Issue] #225, which introduces the first Martian superhero: J’onn J’onzz,

aka Martian Manhunter!

In terms of recent science fiction about Mars, I’d say it’s essential to read Kim Stanley

Robinson’s Red Mars or, if at all possible, the entire Mars trilogy. When those came out,

there was a sense in the science fiction community that, that’s it, nobody will ever write a

better set of stories about Mars. Fortunately, science fiction people like a good challenge

and so there are many other great offerings out there from recent years!

[As a bonus, Robinson listed all of his favorite Mars books for more advanced science fiction fans here.]

In terms of print

fiction, of course I’d recommend Andy Weir’s The Martian. Given the new appreciation of

the Martian landscape for what it is in both the science and science fiction community, I

think it’s no surprise that many recent video games—including Doom, Doom III, and Mass

Effect III, all take place on Mars and/or its moons, where navigating the nonhuman

landscape becomes an important part of the gameplay.

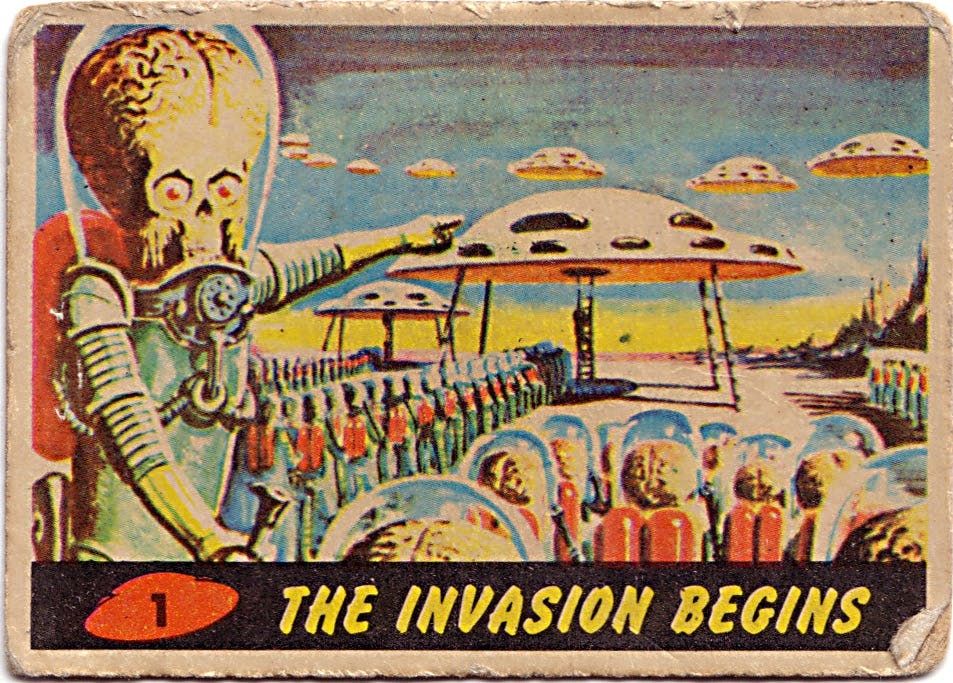

And finally, to prevent the newbie from thinking that the science fiction community is

always sober and serious, I’d recommend a few of the very many and very funny Mars

stories out there, including Warner Brothers’ animated shorts about Marvin the Martian,

director Nicholas Weber’s Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964), and Tim Burton’s

Mars Attacks! (1996). Because if we can’t laugh at ourselves and our hopes and fears about

red planet, then we aren’t going to have nearly as much fun once we get there!

Photo via NASA