Comics legend Grant Morrison turned heads by speculating that Warner Bros. film take on Wonder Woman will be nothing like the character fans have loved for seven decades. But is he right?

It’s no secret that fans have adored the Amazing Amazon for generations. Speaking to the L.A. Times in 2014, Gail Simone put her finger on why:

Wonder Woman is about her sense of justice and compassion and taking care of things that other people may not be able to, but she does have the ability to do it. She’s also brave. She doesn’t have the fear of stepping in and doing that when she can, and all those attitudes are what make her such an amazing, long-lasting character, besides being gorgeous and all those things.

But Morrison, who authored Wonder Woman: Earth One graphic novel for DC, thinks Diana Prince has moved away from the character traits we love most. Morrison shared his thoughts with Nerdist on the direction Gal Gadot’s Amazonian iteration headed for the film franchise:

I sat down and I thought, “I don’t want to do this warrior woman thing.” I can understand why they’re doing it, I get all that, but that’s not what [Wonder Woman creator] William Marston wanted, that’s not what he wanted at all! His original concept for Wonder Woman was an answer to comics that he thought were filled with images of blood-curdling masculinity, and you see the latest shots of Gal Gadot in the costume, and it’s all sword and shield and her snarling at the camera. Marston’s Diana was a doctor, a healer, a scientist.

As one of the few continuously published superheroes in comics, with each passing decade Wonder Woman in particular has reflected America’s changing and evolving political systems and attitudes toward gender. In her current iteration, she’s taken on the role of the God of War, a stance that creates conflict within her due to her longstanding commitment to nonviolence.

So which is the “real” Wonder Woman? And how has the release of the 2017 film changed her character?

To answer that question, we have to look at the way the character has functioned over the years—and how we wound up where we are now.

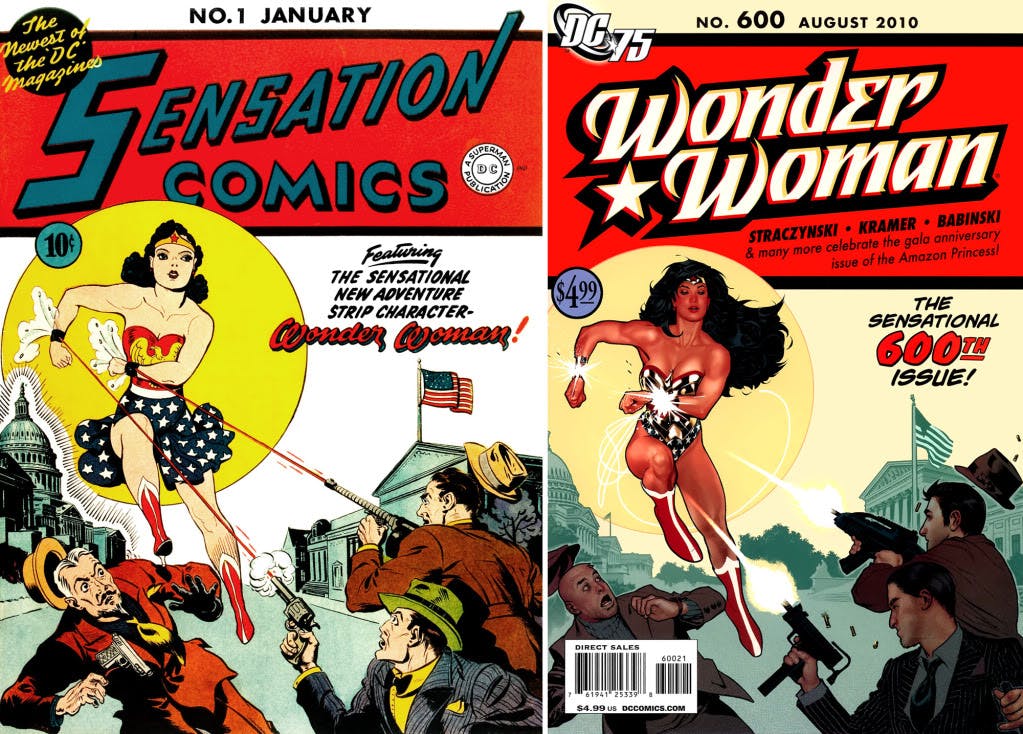

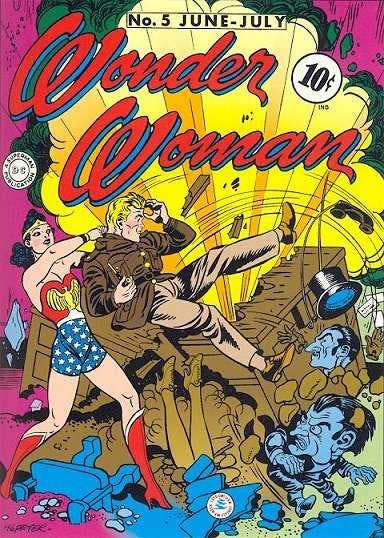

Wonder Woman, 1942—1947

An antidote to “Blood-curdling masculinity”

Wonder Woman was by no means the first female superhero, but she was perhaps the first who was designed to function primarily as a social message. Her creator, psychologist William Marston, intended her to be an antidote to what he had decided was “comics’ worst offense… their blood-curdling masculinity.” By this, he didn’t really mean that comics were too violent or stereotypically masculinized, but rather that they lacked all the elements that Marston saw as the “tender, submissive, peace-loving” feminine ideal.

Marston’s wife, Elizabeth Holloway, was a remarkable woman who earned a law degree from Boston University despite being pressured by her family to become a homemaker instead. Afterwards she assisted in his lab at Harvard, where he would invent a crucial component of the world’s first Golden Lasso, the polygraph test. When Marston, in 1941, first conceptualized a superhero who fought battles with love instead of violence, it was Holloway who told him to make the character a woman.

Is Wonder Woman a feminist?

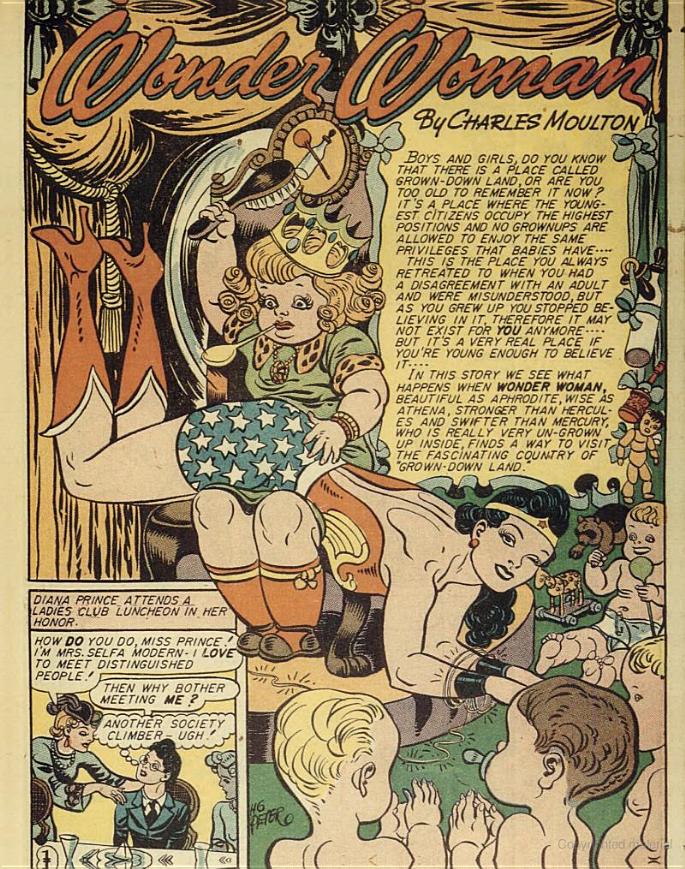

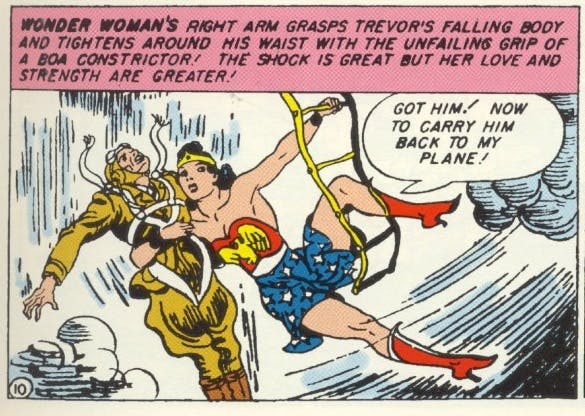

Marston patterned Diana off Holloway and Olive Byrne, a woman with family ties to the feminist movement. Bucking 1940s social norms, Byrne, Marston, and Holloway lived together in a lifelong domestic relationship. Marston wanted Diana to be a role model for comics-loving girls who, like his wife, had rejected quainter ideas of womanhood. Marston saw a solution in a hero who would unite qualities of strength and action with what he saw as feminine submission. Consequently, he made sure that the hallmark of Wonder Woman as a series under his authorship was its continual emphasis on what he called “enjoyable” bondage. Chains, shackles, and paddles abound, and the golden lasso was originally a tool that caused its prisoner to submit and obey in addition to telling the truth.

Wonder Woman and S&M

In 1943, charged to answer for a comic series that was jam-packed with S&M imagery, Marston wrote that “the only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound. Women are exciting for this one reason—it is the secret of women’s allure—women enjoy submission, being bound.”

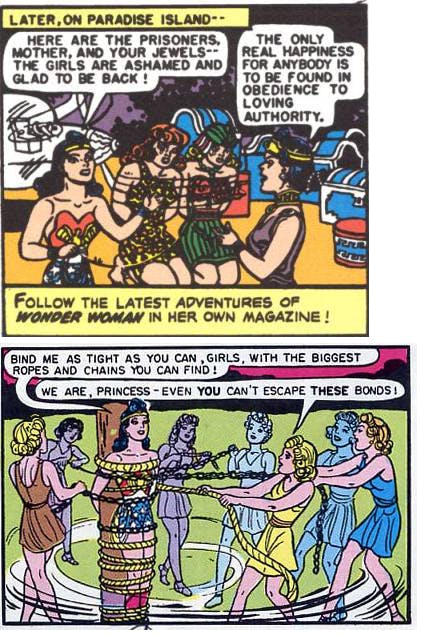

Yet despite this trait, Wonder Woman was also consistently empowered with all the ideals of American patriotism during World War II, and of women newly entering the work force. Time and again she rescued the men around her, particularly her buddy Steve Trevor. Here she is rescuing him in Sensation No. 1, January 1942—her first book and her second appearance ever:

She frequently fought Fascists, and one cover famously had her defeating Hitler himself. In 1943’s summer issue Battle for Womanhood, Wonder Woman liberates the wife of a Nazi-esque villain called Dr. Psycho, and then sternly admonishes her, “Get strong! Earn your own living — join the WAACS or WAVES and fight for your country! Remember, the better you can fight, the less you’ll have to!”

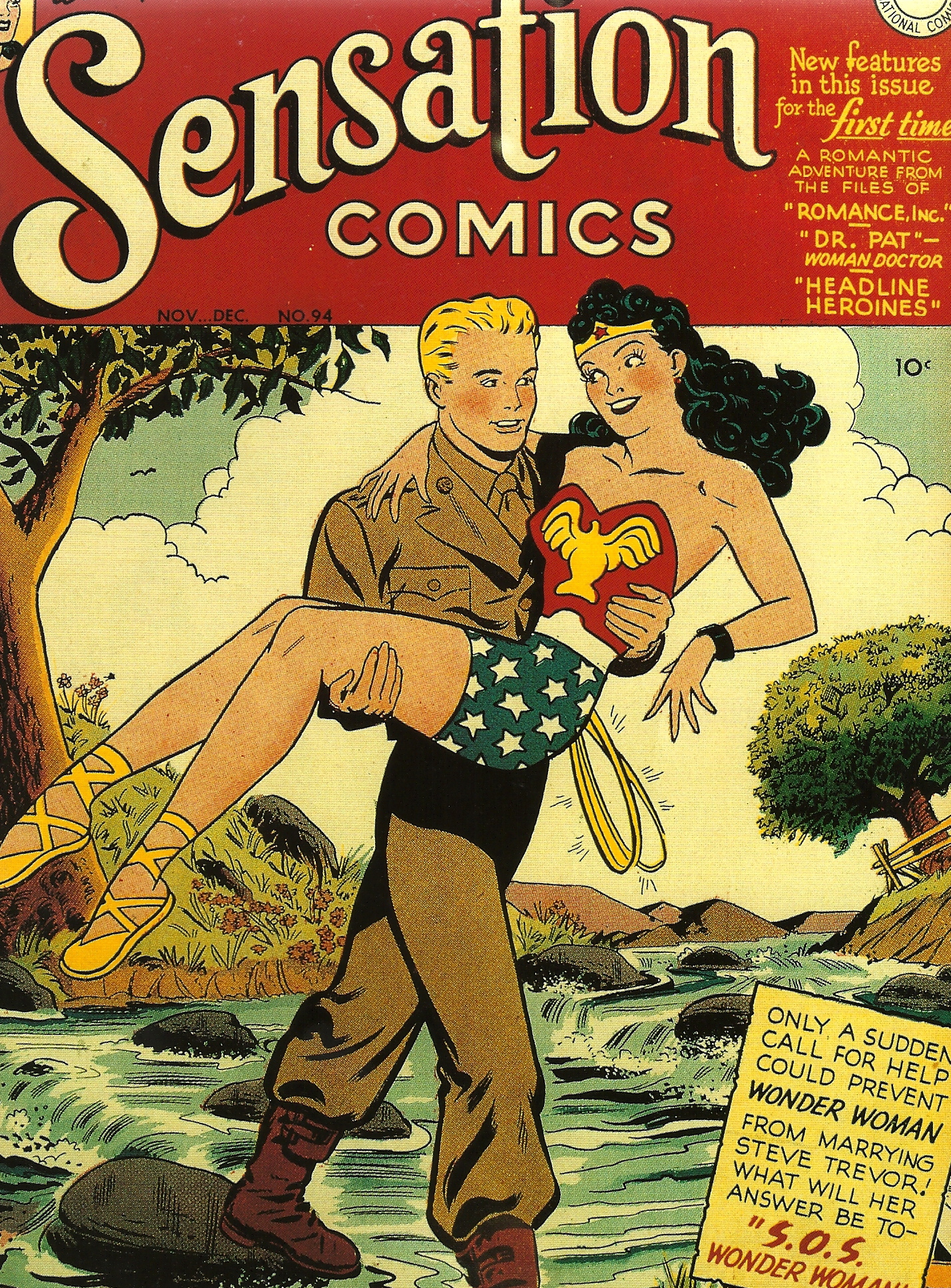

But ultimately, all this action-packed empowerment only lasted as long as Marston himself. When he died in 1947, Wonder Woman’s heroic trajectory took a sharp turn—in the opposite direction. By the end of the Silver Age, Golden Age Wonder Woman would have her entire backstory retconned, be retroactively married off to Steve Trevor, and ultimately lose her power altogether.

READ MORE:

- The complete list of upcoming DC Comics movies

- 7 things you don’t know about Severus Snape

- 10 super accessories every ‘Wonder Woman’ fan needs

1947—The Silver Age

In 1947 writer-editor Robert Konigher took over writing Wonder Woman, and for the next two decades he proceeded to drastically shift her characterization away from the free-wheeling American hero of wartime. Under his reign, and influenced by the push to re-domesticate women of the 1950s workforce, Diana gives up her war office job for a string of Barbie-like careers: romance editor, fashion model, Hollywood actress, a boutique store owner—becoming increasingly passive and objectified through each one.

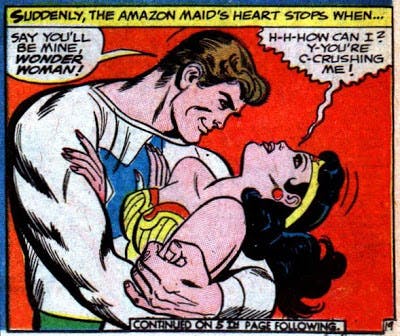

In 1954, due to a moral panic that comics were too subversive, the industry instituted the Comics Code Authority to self-censor anything too immoral, and Wonder Woman suffered as a result: her plot arcs became hopelessly centered around love triangles that further turned her into an object and often showed her being physically fought over like a possession by various men.

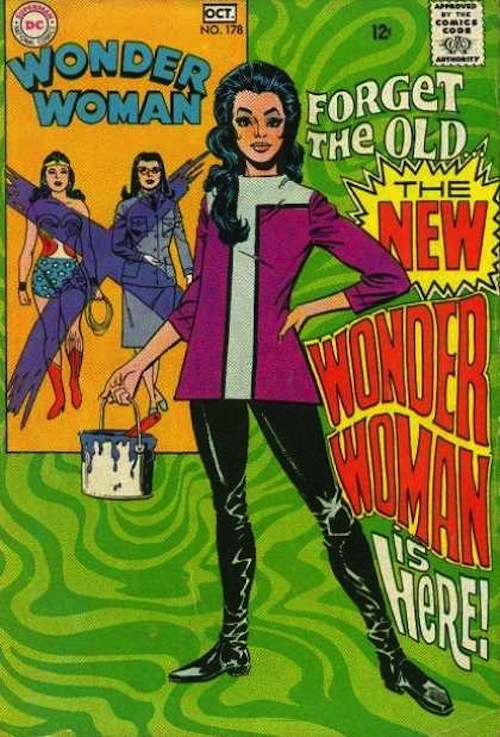

The cover art through the years also reflects these changes, as Diana goes from an assertive, active figure to one routinely made passive and sidelined in her own series. An example is this unpublished cover for Issue #176 in 1968. It was ultimately rejected for the cover on the right, which still depicts a Diana physically submissive and stripped of her confidence by three brothers who proceed to fight over her.

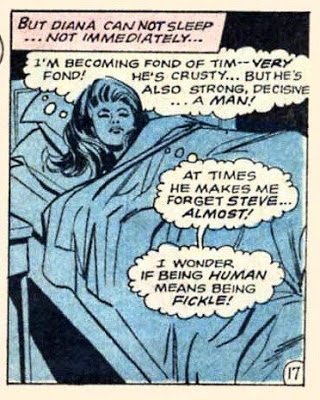

And here’s a look inside that issue:

You get the idea.

Wonder Woman goes mod

By the ’60s, spy movies were all the rage, and Wonder Woman had gained her fair share of gadgets: her own invisible plane, a tiara that also functioned as a boomerang ala Oddjob, and spy radios in her bracelets. Just after the issue above, DC tried to launch a new “Mod Girl” Wonder Woman who was essentially a spy secretary—an Emma Peel for comics fans.

In this series, Diana loses her powers, exchanges her uniform for ’60s fashion, learns Kung fu, and gets bossed around by two new male bosses, one a Sam Spade clone called “Trench” with whom she falls in love. (Steve’s been dead a while by this point.) Although this series dealt with numerous social issues like street harassment and wage gaps, fans hated it—and still do—because it essentially turned Diana into a simpering, naive shopgirl being bossed around by boorish men, and mooning over them anyway.

Thankfully, the 1970s—and the rediscovery that Wonder Woman is awesome—were just around the corner.

The ’70s–today

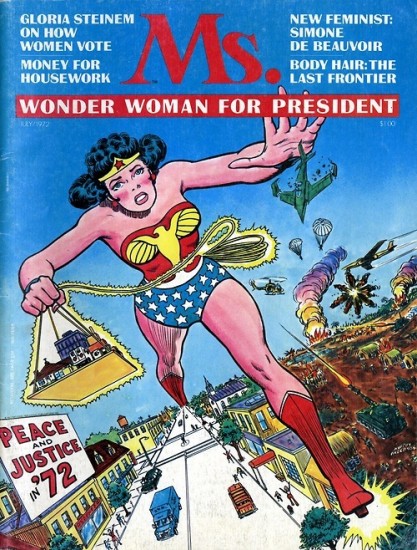

In the 1970s, Lynda Carter’s onscreen depiction of Wonder Woman as a real, empowered woman led to her adoption by radical feminists as a cultural icon. Along with this status came a revival of interest in the character, as well as a return of all her Golden Age qualities of strength and heroic action.

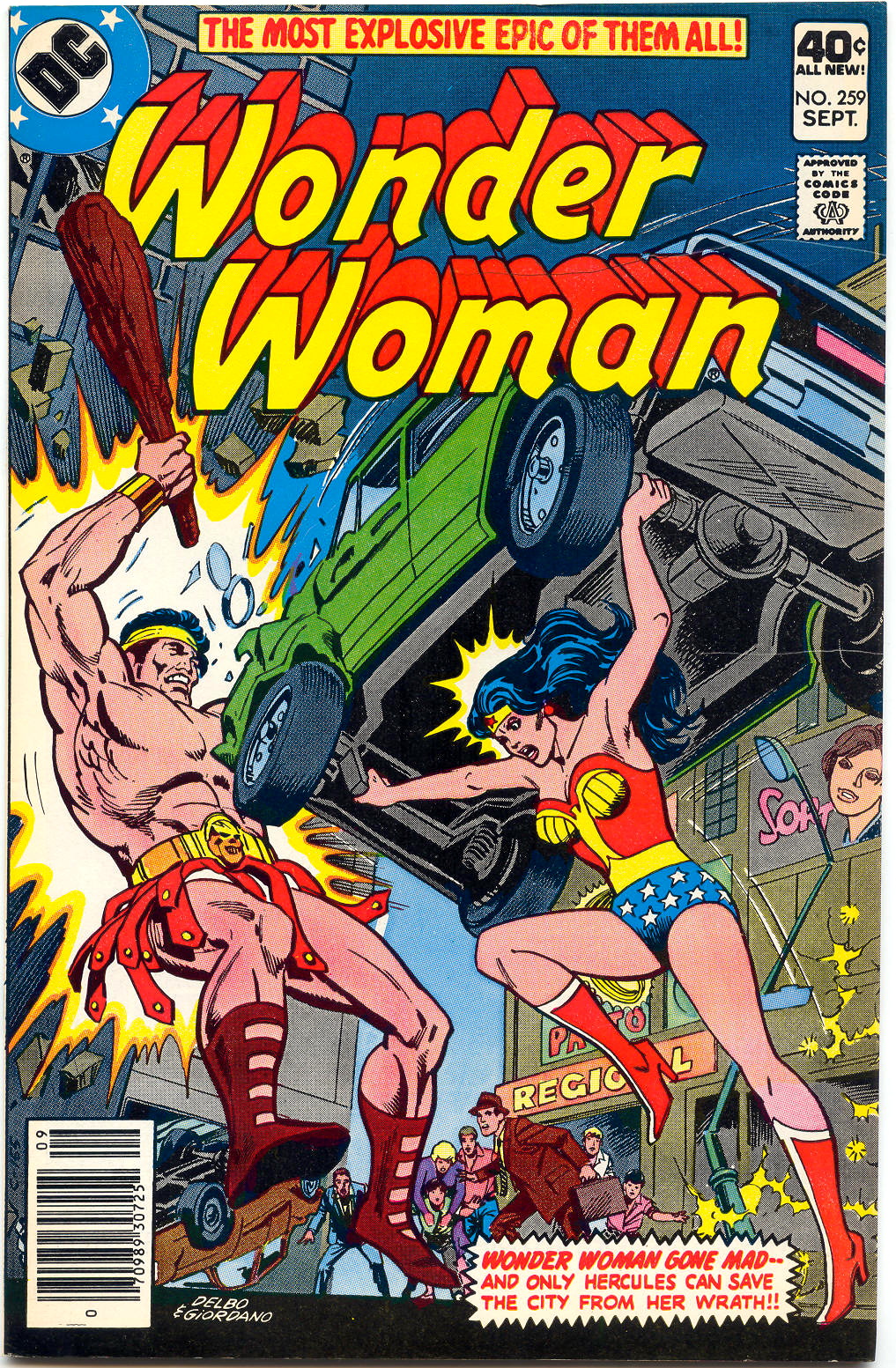

But while women outside of geek culture were discovering the character, comics themselves were growing more insular. By the ’80s, title characters were being written not to appeal for children and idealists of all ages, but for a relatively small community consisting primarily of adult men who wanted specific things from their comics: above all, superheroes kicking ass. In the late ’80s, with George Perez’ series revival, that’s just what they got.

Increasing violence and gore

Perez, a legendary comics artist and writer, wrote Wonder Woman from 1987–1992, streamlining her origin story, tying it more directly to mythology, and making her considerably more warlike in the process. Among other things, while still maintaining her ostensible commitment to nonviolence, Perez’s Wonder Woman grew increasingly prone to indulging in violence as a solution. If it’s possible to tie the Wonder Woman of the film franchise to any previous depiction of Wonder Woman we’ve seen so far, Perez’s Wonder Woman is the closest:

Perez’s take on the character presaged two decades of increasing dalliance with the morally grey side of Diana’s role in the DC Comics universe. Here’s blogger Sean T of Magic Lasso, giving us a rundown on…

…the increasing violence and gore in Wonder Woman’s comic over the last few decades, starting with Perez, who turned her tiara into a beheading device, where servants of Ares devolved into gory flaming corpses, and her challenge from the Olympians essentially turned her into a monster-slayer. In a later story she ripped off the Cheetah’s tale and beat her with it. Under Messner-Loebs, she literally became a leg-breaker. Byrne had Darkseid come to Paradise and slaughter countless Amazons. Jimenez had the Amazons slaughtering each other—a story that concluded in a horrific depiction of the Queen mother as a charred skeleton, the flesh singed from her body. Rucka showed her decapitating Medousa and breaking Max Lord’s neck. Simone showed Diana using, ahem, enhanced interrogation techniques on the Cheetah, ripping her lasso from the flesh of Genocide, and planting an axe in the head of Ares—a violent act made even more senseless when he simply showed up a few issues later with a giant gash and stitches in his head. Some remedy.

In the 90s, Wonder Woman also gained a sword and battle armor thanks to a popular 1996 miniseries called Kingdom Come. Although her character specifically eschewed violence in that arc, she gained a ridiculously powerful sword, which was later joined in the New 52 by two magical swords she can conjure at any time from her bracelets—thus making her even more of an ass-kicker.

New 52’s reboot of the series took a decidedly more cynical approach, both to Wonder Woman’s core origin and its original philosophy. In Issue #7 of Brian Azzarello’s run of the series, for example, Wonder Woman discovers that the idyllic Amazonian society in which she grew up, Paradise Island, is actually full of predatory women who rape and kill their partners and trade their male children into slavery. The narrative takes what was envisioned as an empowered society of women and uses it to create, instead, a straw argument about the ways modern feminism oppresses men.

Along with decades of an increasingly masculinized Wonder Woman, her mantra of nonviolence has been repeatedly undermined. One notable example is her decision to do nothing while witnessing the genocide of her people in John Byrne’s Second Genesis arc. Instead of this decision prompting her to find alternative ways to halt the violence or to focus on strengthening her remaining community of women, it led to this moment of weakness—between Diana and a man she met only the day before:

As a demonstration of Diana’s representation of post-9/11 U.S. politics, It’s all about as unsubtle as you can get.

Wonder Woman takes on 2017

In our interview, Wonder Woman’s current creative team, David and Meredith Finch had plenty to say on the subject of her symbolism. “I still, first and foremost in my mind believe that at her core she’s about love,” Meredith Finch told us. “I still do believe that she fights for everybody’s rights—not just the rights of women, not just the rights of the downtrodden.”

But can she still fight from a position of love while using violence as a tool? We asked comics scholar and Wonder Woman fan Daniel Amrhein of Journey Into Awesome to weigh in. For Amrhein, the Wonder Woman story is “fundamentally about the power of love over war, sisterhood, and empowering women:”

This is where many of her modern creators stumble. Once the character or story loses sight of these themes, things quickly fall apart. At best, we’re left with a generic superhero story. At worst, we’re left with something offensive and antithetical to Wonder Woman’s intent.

“To say I’m worried about [Zack Snyder] bringing Diana to the big screen would be an understatement,” Amrhein wrote in an email. He believes Snyder’s take on comic book adaptations is “the kind of ‘blood-curdling masculinity’ that Marston specifically created Wonder Woman to fight against.”

However, Amrhein also cautioned against romanticizing Marston’s era of Wonder Woman, noting, “Marston was a visionary but he also injected Golden Age Wonder Woman with some very problematic ideas about power dynamics and gender relations.”

Where does that leave us today?

So whether you believe Wonder Woman is the peace-loving answer to society’s violence-consumed ills, or a mighty warrior who’s long overdue for her chance to show off her onscreen fighting prowess, it’s clear that her warrior status hasn’t happened overnight. Rather, it’s been a decades-long process of bringing her characterization in line with overarching industry trends towards militant superheroes and violent altercations.

Ultimately, Wonder Woman has never really been the hero she could be. Even in the Golden Age she was still objectified and her nonviolence used as a stand-in for female sexual submission. Ultimately, we’ve never actually seen a Wonder Woman who’s been empowered enough to radically commit to ideals of peace and love, without being sexualized, objectified, briefly (or totally) compromised, or undermined by her own narrative in the process.

We don’t know what that hero would look like on screen, because we’ve never actually seen her off screen either.

And if we get a different character altogether in Batman vs Superman, we’ll have 70 years of comics, not Zack Snyder, to blame.

Photo via Comic Vine